Kare11

St. Paul teacher’s union paves way to strike

The St. Paul Federation of Educators voted overwhelmingly Thursday to authorize a strike but says a possible strike date will be announced later.

ST PAUL, Minn. — Many teachers across Minnesota have been working without a contract since the deals expired last summer.

In St. Paul, things took a significant turn on Thursday. Members of the teacher’s union overwhelmingly voted to authorize a strike, just like they did two years ago.

Some sticking points include higher wages and more mental health support.

The two have more mediation sessions scheduled but are still very far apart on the biggest issue for teachers – salaries.

“When that divide looks massive, it is because our student needs are massive,” said Erica Schatzlein, the St. Paul Federation of Educator’s lead negotiator. “I do not believe it is right and fair to cost those programs and services and skills that our students need against our contract.”

The district says it’s already facing more than a $107 million budget shortfall, but that it doesn’t, “Believe a strike is necessary to meet the needs of our students, families and staff.”

The SPFE says 92.4% of members voted to authorize a strike, which is higher than when the union authorized a strike in 2022. It narrowly avoided striking after reaching an agreement with the district the day before the action was scheduled to begin.

It’s a pointed move in what’s been a contentious season of negotiations.

“It is different,” said Education Minnesota President Denise Specht. “A lot of it has to do with the fact that they just can’t do it anymore and they need to see some change.”

Specht says settling contracts is also moving at its slowest pace in two decades. Her data shows that since Feb. 13, 2024, 200 locals have settled contracts, which is about 61% of the total 328 regular school districts bargaining this cycle.

Specht says there are also more allowable topics to debate than ever before including staffing ratios and policies, along with rising health insurance costs – many of which are sticking points for Education Minnesota Lakeville.

“There’s workload and there’s finances,” said its lead negotiator Johannah Surma. “There are now more vacancies for teaching positions in this state than there are teachers to fill them, so we need to compete in this market and hire the best teachers for our community.”

The union has been rallying and packing school board meetings during negotiations. Surma said the union and the district held its first bargaining session on Tuesday which lasted nine hours.

“I don’t see the district as negotiating against us, it’s really negotiating against the market,” said Surma, who says class sizes there are some of the highest in the metro.

The union is asking, in part, for a 5% pay increase, which is also what the Anoka Hennepin teacher’s union just secured for its first year. It got another 3% the following year.

It approved the contract this week which also includes health insurance district contributions, a one-time bonus and more language changes than any other contract in recent history.

The district said the school board expects to consider approval of the contract at their Monday, Feb. 26. meeting. The contract costs about $64 million, part of which is paid for with last year’s session’s historic education funding, which Specht says makes up for all the years education was underfunded.

“Whatever tactics they’re taking or decisions they’re making, a lot of it has to do with the fact that they just can’t do it anymore and they need to see some change,” said Specht.

As for the St. Paul school district, its spokesperson wrote in a statement, “This vote does not mean there will be a strike, nor does SPPS believe that a strike is necessary in order to meet the needs of our students, families and staff. SPFE and SPPS have been negotiating these contracts since September and agreed to seek mediation in December. Four full-day mediation sessions have taken place this month, and two more full days of mediation are scheduled for Feb. 23 and March 1.

The main issues that remain unresolved are wages, health insurance, and other proposals that have significant costs. The new funding from the state is helpful, but many requirements dictate how it must be spent.

Even with this funding, SPPS is facing a budget shortfall of approximately $107.7 million for next year. This is due to several factors, including the expiration of COVID relief funds, years of declining student enrollment, increased operational expenses, and other investments that SPPS has made to provide the services our students and families value most, including yellow buses, reading supports, school safety measures and more.”

KARE 11 also reached out to the Lakeville School District on Friday but didn’t get a response by the time of publication.

Watch the latest local news from the Twin Cities and across Minnesota in our YouTube playlist:

Kare11

As NIL changes college sports, calls continue for more oversight

As the leading scorer for the undefeated Gopher women’s basketball team, junior guard Mara Braun is among the more recognizable athletes on the University of Minnesota campus.

The Wayzata native, a four-star recruit out of high school, chose to enroll in her flagship state university in the fall of 2022 despite scholarship offers from several other power-conference schools. On the court, she has already made her home state proud, earning Big Ten All-Freshman honors during her first season and then Big Ten Honorable Mention last year during an injured-shortened sophomore campaign.

“To be able to play in front of my family and friends,” Braun said, “and to show our loyalty to the state and the program, it just means the world.”

Outside of Williams Arena, Braun has also grown her brand considerably by taking advantage of new NCAA policies around Name, Image and Likeness (NIL). The rules, implemented in 2021 as the result of a U.S. Supreme Court ruling, have transformed college sports by allowing athletes to profit from sponsorships and advertising for the first time in the NCAA’s history.

Through this new world of NIL, Braun has forged corporate partnerships, such as the one with Affinity Plus Federal Credit Union that placed her image on a University Avenue billboard last year and currently shows her on the front of a light rail train. Braun has also been heavily involved with Special Olympics Minnesota, which is personal to her through her own family.

With more than 26,000 followers on Instagram, Braun has used NIL to raise visibility both for her causes and for the Gopher women’s basketball program as a whole.

“Just knowing what you believe in, standing on that, and using your platform to advocate — for me, it’s Special Olympics. For others, it might be some other organization,” Braun said. “How can I be active in the community and give back to the community? That’s a huge part of why NIL is so important to me within this state.”

Over the past three years, records show that hundreds of Gopher athletes like Braun — and thousands nationwide — have entered into a wide range of NIL deals with various companies, nonprofits and other organizations, helping the players to finally earn financial compensation within the multi-billion-dollar industry that is college athletics.

For many, the shift is long overdue.

In the NCAA v. Alston case that paved the way for NIL in 2021, Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote in his concurring opinion that “the NCAA’s business model would be flatly illegal in almost any other industry in America,” referring to the system in which schools and conferences collected millions in ticket and media revenue without the players seeing a cut outside of their scholarships and stipends.

Yet, at the same time, the emergence of NIL has drastically altered the landscape of college sports. With no federal regulations around NIL and only a patchwork of state laws, there is very little public transparency around how the deals work, which people or entities are providing the money, and exactly how much money they’re worth.

To make matters even more complicated, NIL went into effect around the same time as the NCAA’s loosened transfer rules, which allowed players to switch schools without sitting out a year. That has created scenarios where players leave programs to enter the “transfer portal” in the off-season — or even in the middle of the year — amid rumors that they got a better NIL deal somewhere else.

“I think everybody is totally supportive of Name, Image and Likeness. We think it’s awesome a young man or a young woman can earn some NIL money off their NIL rights,” University of Minnesota Athletic Director Mark Coyle said. “But we need more clarity as we move forward. It’s been the Wild, Wild, West.”

Chapter 1

NIL at Minnesota

As a charter member of the expanded Big Ten, now one of the largest and most powerful of the major conferences, the University of Minnesota operates within the structure of big-time NCAA athletics. Without question, Name, Image and Likeness has become a key component of Gopher athletics and a critical part of staying competitive with the rest of the league.

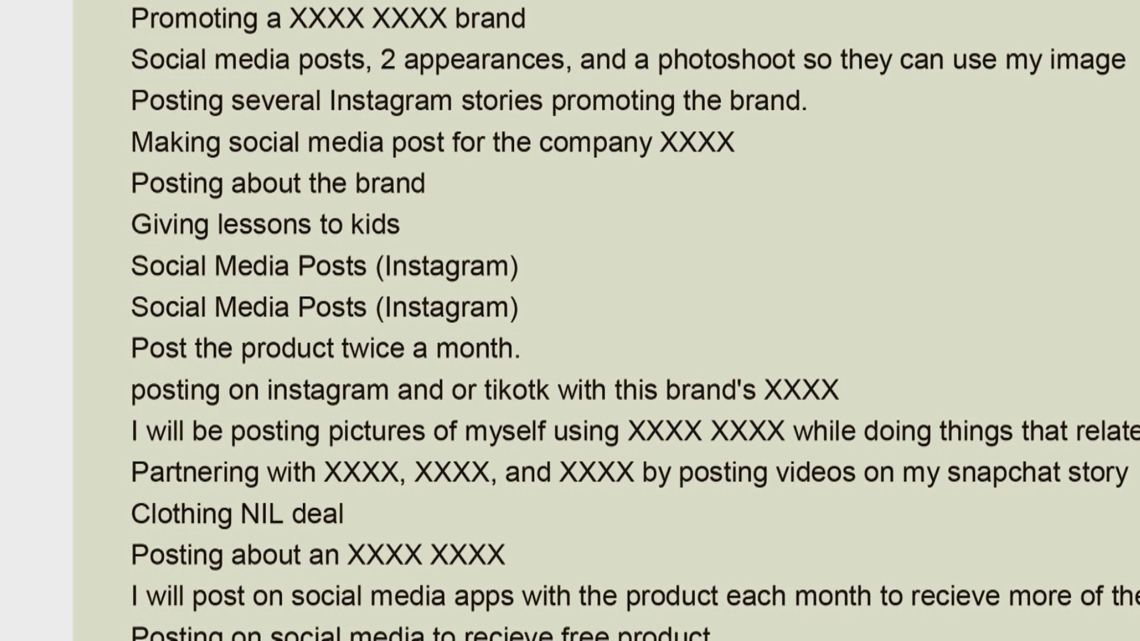

According to documents obtained by KARE 11 through the Data Practices Act, Gopher athletes have reported more than 500 NIL deals to the university dating back to the fall of 2021, with roughly an even split between men’s and women’s athletics.

Since names are redacted and payments are listed inconsistently or not at all, these documents cannot provide a full account of the monetary value of these deals. Players are not required to disclose their NIL income publicly, and in some cases, they indicated payment amounts such as “TBA,” “still being figured out,” or “no set amount.” Other deals were based on merchandise sales, meaning the income for the player was dependent on how many products were sold.

However, the NIL documents still provide some insight into how much money players are able to make through NIL. According to the data, U of M athletes have reported at least $450,000 in known NIL payouts over the last three years, with tens of thousands of additional dollars generated through monthly payments and merchandise sales commissions. The single largest reported deal belonged to a football player, who made $25,000 from an autograph session last fall. A men’s basketball player also reported $20,000 monthly NIL payments for “making live appearances at various events, signing autographs, and making social media posts.”

Meanwhile, in 2022, a women’s hockey player told the school she made $7,500 for wearing gear and allowing a company to promote her image on social media, and a volleyball player similarly made $10,000 for marketing posts over the course of a full year. On the lower end of the spectrum, some athletes reported making a few hundred dollars for social media posts or appearances, and others used NIL to run camps and clinics for young players. Some of the NIL arrangements were not worth any money at all.

Many of the NIL deals are coordinated through a “collective” known as Dinkytown Athletes, which operates in close partnership but separately from the University of Minnesota. Almost every major university in the country now has an NIL collective like this one. Wisconsin has The Varsity Collective, Michigan has Champions Circle, and Iowa has Swarm Collective, to name a few in the Big Ten.

Dinkytown Athletes was co-founded in 2022 by Derek Burns and Robert Gag, who were previously business partners at a Minnesota-based company known as Tierney. Burns is a former Gopher football player with a degree from the Carlson School of Management, while Gag is a lifelong Gopher fan with an extensive background in sales management.

“A collective is essentially a talent agency. We are representing the student-athletes at the University of Minnesota,” Gag said. “There’s definitely a lot of money involved in college sports. Student-athletes should be getting a piece of that pie. They’re the ones going out on the courts, on the field, on the rink. They definitely deserve it.”

Dinkytown Athletes works directly with players to connect them to sponsorships and corporate partnerships, while also relying on donors and monthly memberships for contributions. These memberships give fans access to meet-and-greets and other exclusive events, providing interactions with major athletes like Mara Braun.

“They’re really good about giving us opportunities and just expanding to get out to fans, and get that support behind them. We’ve done a lot of really cool things within the community,” Braun said. “Dinkytown Athletes has done a great job communicating with us, the dos and don’ts of keeping us safe as athletes and making sure our privacy is taken care of.”

According to Gag, Dinkytown Athletes has represented more than 300 athletes so far, and the group’s memberships have doubled year over year. Last month, Dinkytown Athletes announced a major partnership with Nepsis — its largest to date — as part of a “million dollar match” campaign. Head football coach P.J. Fleck has praised Dinkytown Athletes and the school’s commitment to NIL, saying recently that he’s “really excited about where we are and the progress we continue to make every single day.”

Gag didn’t reveal specific details about Dinkytown Athletes’ finances or operations, but as the school’s own data indicates, the deals vary widely in structure and value.

“We’re a private company, so for competitive reasons with others, we’re not going to get into dollars as it relates to the U of M. I will say, it’s the 80-20 rule,” Gag said. “There’s a top group of student-athletes in the country that might be making the six-figure, to seven-figures [annually]. The rest is just a really manageable… let’s just say, $5,000 range.”

Without any requirement for athletes to disclose income, NIL deals have become subject to speculation across the country. The website On3.com, which covers college and high school sports, lists NIL valuation in the millions for top athletes like Colorado quarterback Shedeur Sanders, LSU gymnast Livvy Dunne and Duke men’s basketball freshman Cooper Flagg. Hopkins native Paige Bueckers, the projected top pick in next year’s WBNA draft, has a listed NIL valuation of $1.4 million while playing for UConn this year.

Although these players do not represent the norm, the estimated value of these deals illustrates how much money is now exchanging hands between third-parties and college athletes.

For that reason, some of the leading voices in college sports are calling for more oversight.

Chapter 2

Calls for change

During an interview at his office this fall inside the University of Minnesota’s Bierman Athletic Building, athletic director Mark Coyle emphasized repeatedly how much he supports the basic concept of NIL. Beyond making extra income on their Name, Image and Likeness, Coyle pointed out that the NIL deals can help athletes with valuable career connections and even teach them how to file taxes.

“It’s created really good lessons,” Coyle said. “I feel like they’re learning and getting educated.”

However, Coyle — who has worked at institutions across the country and also serves on the Division I Men’s Basketball Committee — said the current model of NIL is not sustainable.

“There’s not an athletic program in the country that wouldn’t say they want some sort of guidelines and regulation,” Coyle said. “I think you see at some institutions, I’m not sure it’s true NIL. You hear the term, ‘pay-for-play,’ where they’re recruiting kids on NIL deals. Are those deals real? Are they false?”

Almost every week, a development related to NIL makes the news.

Earlier this fall, UNLV quarterback Matthew Sluka made headlines when he decided to leave his team three games into an undefeated season, supposedly over a dispute involving NIL money that Sluka’s family said he had been promised. Weeks later, Sluka entered the transfer portal to seek opportunities with other football programs.

Coaches have frequently lamented the lack of guardrails around NIL. Nick Saban, who retired in January after steering Alabama to six national titles in football, addressed federal lawmakers in March about NIL issues and said that “all the things I believed in for all these years, 50 years of coaching, no longer exist in college athletics.”

Just last month, Virginia men’s basketball coach Tony Bennett also cited NIL specifically as one of the reasons for his own retirement.

“I think it’s right for players, student-athletes, to receive revenue. Please don’t mistake me,” said Bennett, whose UVA team won the national championship in Minneapolis in 2019. “But the game and college athletics is not in a healthy spot. It’s not. And there needs to be change.”

Although the NCAA and universities have created their own guidelines, there is no federal law providing oversight of Name, Image and Likeness. Many states have passed their own laws, but they’re all different, and Minnesota does not even have an NIL law on the books yet.

The NCAA’s new president, former Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker, has called on Congress to establish national NIL policies.

“We continue to see evidence of dysfunction in today’s NIL environment, including examples of promises made but not kept to student-athletes,” Baker wrote on social media in September. “Just as anyone that owns stock or buys a house is afforded basic consumer protections, it’s clear that student-athletes entering NIL contracts should be too.”

Coyle said a federal measure on NIL would help regulate the current “Wild, Wild, West” of college athletics, particularly to improve transparency around the NIL deals.

At the same time, there’s also a legal settlement moving forward right now that may significantly alter the NIL model — and even lead schools to pay players directly.

Chapter 3

Legal settlement

This fall, U.S. District Judge Claudia Wilken gave preliminary approval to a $2.8 billion settlement that will reimburse current and former athletes who competed in college sports dating back to 2016 — prior to the Name, Image and Likeness era. These damages, which stem from three antitrust lawsuits filed against the NCAA, will be paid out over a decade, equaling about $280 million per year. Depending on the sport, individual players could receive tens of thousands of dollars as a result of the settlement, with some football and men’s basketball players receiving six figures.

If finalized this spring, the settlement will also set up a revenue-sharing system next year between universities and the athletes, a seismic development that would permanently change the NCAA’s longstanding amateur model.

In short, revenue-sharing means schools will start paying players directly through their athletic department budgets, although outside NIL deals will still be permitted. Under the terms of the settlement, power-conference schools will be able to distribute approximately $21.5 million to whichever athletes they choose. (That figure is based on the average revenue from media, sponsorships and ticket sales across the major leagues in college athletics).

At the U of M, Mark Coyle and his athletic department are still sorting through what the revenue-sharing agreement means for Gopher athletics.

“We’ll be able to potentially share that revenue with student-athletes in certain sports. So, each institution can decide if they want to give that money to all student-athletes, [or] if they only want to give it to one student-athlete,” Coyle said. “You have a lot of flexibility.”

However, revenue-sharing is unprecedented territory for athletic departments, and there are a wide variety of concerns about how this could impact athletes. For example, with football and men’s basketball programs earning the majority of the revenue, there are questions about what the plan would mean for Title IX and whether female athletes would get a fair revenue cut.

Also, with the added strain to athletic department budgets, the so-called Olympic sports — like gymnastics and swimming — could find themselves at risk across the country. Sarah Hirshland with the United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee said these concerns are “extraordinarily top of mind” and told the Associated Press that she will “keep a close eye on programs being cut, or even talked about being cut.”

Mark Coyle acknowledged that the U of M will need to adapt to the new revenue sharing model.

“There’s not an athletic program across the country that isn’t stressed right now financially,” Coyle said. “We’re working closely with [University President Rebecca Cunningham] and our Board of Regents to identify revenue sources as we move forward, and it’s going to fall on us. Our board has made it very clear, let’s have a balanced budget. We’ve been able to do that each year with the exception of the COVID year. So, again, departments are going to have to find that revenue, they’re going to have to work with their campus partners to generate that revenue, but no doubt, there’s pressure on every athletic program.”

The legal settlement involving the NCAA would also increase transparency around NIL deals, including the creation of a “clearinghouse” to track payments worth more than $600. This way, schools would have a better understanding of how the NIL deals are structured and how much they’re worth.

NIL deals will take on a different look after revenue-sharing starts, but Robert Gag with Dinkytown Athletes still sees his collective as an important part of the college sports ecosystem.

“Particularly as it relates to memberships, there’s going to be always a role with collectives,” Gag said. “I believe collectives are going to be here forever.”

Chapter 4

The future of college athletics

Between NIL and revenue-sharing, college athletics are undergoing a fundamental transformation.

And there’s no going back.

“It is a new world in college sports, and a new sense of what amateurism means, because it doesn’t mean much anymore. And you can’t blame the players,” said Bob Stein, an All-American football player for the Gophers in the 1960s who later played in the AFL and NFL. “It’s a tough thing to see, such a philosophical change for us old football players who didn’t get paid… I don’t think it’s a bad thing, but it’s surely a different thing.”

Stein, who is also an attorney, has followed NIL developments closely in recent years and spoke on the topic at a symposium at the University of Central Florida. At that event, he said most of the panelists — ranging from league commissioners to athletic directors — came to the same conclusions.

“That what this is going to create, is a segmentation,” Stein said, “a very clear segmentation of the people who can play in the big-dollar game, the people meaning the schools, and the ones that couldn’t, that didn’t have the resources or didn’t want to commit the resources to paying big money for the best players.”

To some degree, this segmentation already exists in college athletics. There has always been an arms race for facilities, resources and coaches, and currently, there are seven college football programs that pay their head coaches more than $10 million per year. Not to mention, the Big Ten Conference is in the middle of a seven-year, $7 billion television contract with NBC, CBS and FOX.

Now, in the NIL era, the players are starting to see some of those dollars flow to them.

“I have no doubt it’s certainly positive for the player,” Stein said. “Any time, in any business that you can get paid based on what the market will pay for you right now, that’s the best possible situation.”

For Mara Braun, though, NIL represents something more than just revenue.

She believes the added visibility from NIL has helped grow the fan base for Gopher women’s basketball, while also affording her the opportunity to gain connections in the Twin Cities business community and raise awareness for organizations like Special Olympics Minnesota.

“I feel like I have the right intentions and values going into NIL. It can definitely get messy if you don’t have that good foundation behind you,” Braun said. “Putting yourself in that spotlight makes you a valuable person to the community. That’s what is important to me. If you do those things, you’re going to be set up really well for the future and NIL is definitely giving me those resources.”

Kare11

Xcel’s massive solar project already online

Massive solar farm near Clearwater will eventually cover 5,000 acres and produce enough electricity to power 150,000 homes.

MINNEAPOLIS — Xcel Energy celebrated a clean energy milestone Tuesday, marking the completion of the first phase of the utility’s massive Sherco Solar Project near Clearwater.

Company executives, contractors, union leaders, utility regulators and government officials gathered at the edge of the immense array of solar panels for a ceremony calling attention to the fact that power has started to flow to the regional power grid.

“As the largest clean energy project in the upper Midwest, this project demonstrates we’re not just talking about clean energy, we’re actually building it,” Xcel CEO Bob Frenzel told those who gathered at the site Tuesday. “Our clean energy vision is about sustainability, but it’s also about energy security. It’s about reliability. It’s about economic prosperity for all, for our customers, for our communities.”

Xcel Energy has invested heavily in wind energy in the past, but the Sherco project is the utility’s largest solar venture. It’s strategically located to connect to the grid at the nearby Sherco Energy Center, a coal-fired plant that is being phased out after serving as the main source of electricity in the area for decades.

By the time the Sherco Solar Project is finished in 2026, the complex will feature 1.5 million solar panels spread across 5,000 acres. It will be capable of generating 710 megawatts, which is enough juice to power 150,000 homes.

The utility is also launching a major battery storage project at the same site, and will be testing new technologies for capturing and holding the energy.

Frenzel noted that while Xcel has closed 24 coal-burning units across its system in the past 15 years, it hasn’t resulted in any staff losses in those communities.

Ryan Long, Xcel’s president for the Minnesota and Dakotas region, thanked the utility’s partners for the roles they’ve played in making a transition to clean energy.

“We can do all of this and keep bills low for customers,” Long told the crowd. “The investments we’re making bring back hundreds of millions of dollars in federal grants to Minnesotans, and back to our customers through lower bills.”

Long said Xcel will continue to take an “all of the above” approach to renewable energy sources, which includes extending the lives of the state’s existing nuclear power plants.

“We’re going to invest in hundreds of megawatts of new battery storage, but we’re also going to extend the lives of our nuclear facilities, which provide around-the-clock carbon-free energy on our system and really will become the new backbone of our generation system as we move through this energy transition.”

Xcel invited Governor Walz to the solar launch, to thank him for setting high goals for carbon-free sources of energy and supporting legislation that will make it easier to build transmission lines connecting renewable energy projects to where the demand exists.

“We’re proving for the rest of the country this is not an either/or choice. We are producing energy across the spectrum, from nuclear, to natural gas, to the clean energies you see here,” Walz remarked. “When you look at this happening, this is what the future can look like. And the future is bright.”

Instead of the traditional ribbon-cutting photo op, they held a symbolic “plug-in” ceremony, to highlight the fact phase one of Sherco Solar is already generating electricity.

Katie Sieben, who chairs the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission, said the project represents a collaboration of many stakeholders. She also noted that Xcel and its contractor Blattner Energy of Avon have complied with mandates to pay prevailing wages, logging 730,000 hours of work by union members on the solar project.

She thanked Xcel for starting the project in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We needed Minnesotans to get back to work. We knew we needed help building our clean energy future. And, thanks to Xcel’s vision, leadership, and perseverance, they brought a really wonderful project to Minnesota.”

Chris Hodrick of Blattner Energy thanked the unions by name, which include Operators Engineers Local 49, LIUNA Local 563, Ironworkers Local 512, IBEW Local 292, and IBEW Local 160.

He also gave a shoutout to the communities around the Sherco Plant for welcoming his crews and subcontractors.

“With the towns of Becker and Clearwater the support here has been tremendous. It’s important for us because we’ve become part of the community.”

Kare11

Eden Prairie man sentenced for COVID relief fraud

The 75-year-old is accused of spending the Paycheck Protection Program money on himself.

ST PAUL, Minn — An Eden Prairie man was sentenced to seven years behind bars for Covid relief fraud, with officials saying he applied for more than $2.1 million in funds which he spent on himself.

U.S. Attorney Andrew M. Luger announced in a press release Harold Bennie Kaeding, 75, of Eden Prairie was sentenced to more than seven years in federal prison. He was convicted of wire fraud, aggravated identity theft, and money laundering.

In the first three months of the Covid-19 pandemic, Luger said Kaeding used the name of close family members to submit loan applications for different corporate entities, that were either defunct or not in existence when the pandemic began.

Kaeding was accused of fabricating tax documents, manufacturing bank statements, and submitting records to ensure the applications appeared legitimate. He initially received $1,642,670, Luger said, but banks realized the irregularities and were able to get some of the money back.

“Among other things, Kaeding used the money to get his personal residence out of impending foreclosure, purchase an SUV, and stockpile more than $80,000 in cash,” Luger said.

Kaeding was arrested in Columbia, where officials say he fled to when he learned he was under investigation. He was found guilty at a jury trial in August.