CBS News

142 Days in Gaza I Sunday on 60 Minutes

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

Book excerpt: “The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi” by Wright Thompson

Random House

We may receive an affiliate commission from anything you buy from this article.

Author Wright Thompson’s New York Times bestseller, “The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi” (Random House), explores the culture of silence that enveloped the Mississippi Delta over the 1955 murder of Emmett Till.

Read an excerpt below, and don’t miss Jim Axelrod’s interview with Wright Thompson on “CBS Sunday Morning” December 1!

“The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi” by Wright Thompson

Prefer to listen? Audible has a 30-day free trial available right now.

One afternoon Stafford Shurden took me through his family’s land. A Taurus semiautomatic pistol rested casually on his console. His family footprint once stretched to the gates of Parchman, the infamous Gothic prison farm that serves as the Mississippi State Penitentiary, one of the worst and most feared prisons in the country. The front gate is twelve miles north of the barn.

At the end of the drive we stopped at his family’s old farm office, which would have been buzzing with people back when the Shurdens ran this little corner of the world. Now it’s empty. He found a key on a big ring and opened the door.

We stepped into the dark, silent room. The first thing Stafford did was go sit in his father’s old desk chair made out of a green bucket seat from an old classic Thunderbird. He hoped the old man would be proud of him. A painting showed Black cotton pickers moving through a field with their long bags, with the Shurden Farms logo on the trailers parked around them. Stafford sighed.

“Tell me this ain’t the most racist s**t you’ve ever seen,” he said.

There was a walk‑in safe and a poster on the wall: Every morning in Africa, a lion wakes up. It knows it must run faster than the slowest gazelle, or it will starve. It doesn’t matter whether you’re the lion or a gazelle—when the sun comes up, you’ d better be running.

There was an oil painting of a stern old woman.

“That’s Grandma Shurden,” Stafford told me. “She had eighteen kids.”

A family crest, commissioned by Otha Shurden in 1969, has soybeans, cotton, and catfish on it. Grandma Shurden was Clint’s mom, too. In a little side office was a huge map of their part of Sunflower County. It documented who owned every piece of land, divided into squares and rectangles and trapezoids, into little homesteads and big plantations. I looked down at the corner and saw the date: “Jan 1, 1956.”

This was the first county land map made after the murder. I ran my finger along the sides of the map and found the barn: Township 22 North, Range 4 West, Section 2, West Half, measured from the Choctaw Meridian. Familiar names claimed plots all around the old Milam farm. Smaller pieces of land were marked only by initials. I found the Dougherty Bayou and all the nearby farms and then the barn. It was the only piece of dirt on the map without a name.

Thomas Jefferson wrote a law that would pass Congress as the Land Ordinance of 1785. His goal was simple. He wanted the empty open space of his new country to be broken into small blocks and sold to yeoman farmers—small, entirely independent (white) landowners—and so he took a system invented by a military engineer named Thomas Hutchins and codified it into law. Many ancient cultures were built around the idea of shared land. America was built around the idea of owning parceled land. That foundational urge was born in the moment when Jefferson put pen to page. Yeomen weren’t plantation lords like Jefferson and they weren’t poor white trash. To Jefferson their protection and elevation in American life was the hill upon which this new nation would live or die. The first draft of the bill broke the country into ten‑mile‑by‑ten‑mile squares called hundreds, while a second reduced them to seven‑mile‑by‑seven‑mile squares called townships. On May 3, 1785, William Grayson of Virginia made a motion to change the seven to a six and James Monroe seconded the motion. They would send surveyors out into every bit of new territory America amassed—starting with the land won from the English in the Revolutionary War—and divide it into thirty‑six‑square‑mile blocks, which would be divided into thirty‑six smaller squares named sections. Each section was 640 acres, or one square mile, and the sale of all this public land would pay down the war debt of the new nation, which hadn’t yet been able to agree on a way to raise money through taxes. A permanent grid appeared overnight.

A central American conflict was baked into this first drawing of the new nation. Jefferson wanted the land to be settled by yeomen. But the price for the newly available land was simply too high for most farmers to pay. In the decades that followed, Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist Party and Jefferson’s Republican Party fought over this issue. From John Adams through Jefferson and into Madison and Monroe, the minimum purchase amount (and the price) rose and fell depending on whether those in power wanted to help capitalist landowners or small, independent farmers. The Land Law of 1800 reduced the minimum purchase to 320 acres, which was cut to 160, then again to 80, and finally, in 1832, to 40 acres. The base price was about a dollar an acre. This fight between capitalized investors and small farmers dominated the politics of the new nation and would play out brutally on the land surrounding Drew, Mississippi.

The barn sits on the southwest quarter of Section 2, Township 22 North, Range 4 West, measured from the Choctaw Meridian. That’s its exact legal location on Jefferson’s grid: a square mile per section, thirty‑six sections per township, over and over again across the new nation. The thirty‑six square miles of Township 22 North, Range 4 West, have borne witness to the birth of the blues at the nearby Dockery Plantation, to the struggle of Fannie Lou Hamer, to the machinations of a founding family of the Klan, and to the death of Emmett Till.

To get to Dockery, take a right out of Jeff Andrews’s driveway, take another right on Ralph Ray Road toward the Bolivar County line, and then turn left on Dockery Road. Dockery Farms has been called the birthplace of the Delta blues by B. B. King and many others. It’s not an accident then that this land fueled the first protest music. The blues came from the land around the barn. From Charley Patton, the Black grandson of a white man. Patton’s music flowed from a place of rage about how he lived a small, threatened life because his grandmother was Black — “skin the color of rape,” the poet Caroline Randall Williams wrote. He became the first blues star, the man who taught Son House, who taught Robert Johnson, who taught Muddy Waters, who hailed from the same Delta town as Sam Cooke and Nate Dogg, all these genres making the same protest music against the same forces as Patton—Delta blues or G‑funk, Muddy and “I’m a full‑grown man” or Sam’s “A Change Is Gonna Come” or Ice Cube and “F**k tha Police.” Eazy‑E’s grandparents ran a grocery store sixteen blocks up Broadway in Greenville from the house where J.W. Milam lived when he died.

The Dockery family still owns their plantation. Now the granddaughters of the founder control the business. One of them, a distinguished elderly woman named Douglas Dockery Thomas, agreed to meet me in her New York apartment. Her building is on the Upper East Side, overlooking the Metropolitan Museum and Central Park. She’s on the board at the Metropolitan Opera and is one of the central patrons of the Met. The doorman was expecting me. The elevator opened directly into her apartment, which covered an entire floor, easily more than four thousand square feet.

She led me into a formal parlor with a piano under tall ceilings and crown molding. I looked down at the museum and the yellow cabs on Fifth Avenue. Hers is some of the most expensive residential real estate in the world. The final vapors of the Gilded Age moved through the empty rooms in a world where history stopped in 1929, or maybe 1955. Nothing we talk about can be on the record, she says. The family remains very private. Her son, I’ve read, is an incredibly successful venture capitalist, the money behind Venmo and BuzzFeed, among others. We talked about Mississippi. Our families knew each other. On a side table was a picture of her with King Charles III when he was Prince of Wales. I noticed her sharp cheekbones and delicate wrists. She loves the opera but also loves the blues and has set up Dockery as a living museum to honor her parents, Joe Rice and Keith, and the music that came to life on the family farm. Her mother especially seemed to understand that the line all white southerners need to see or be shown wasn’t between good and bad, but between cowardly and brave.

“If I had not been married to Joe,” Keith said, “I might have been out on the streets marching with the protestors. But I was, and I didn’t.”

Willie Reed stepped out of his family home for the last time on a Friday night. He moved alone into the darkness. He had been told the plan and followed it carefully. Lots of people wanted him dead. He’d dared to accuse a white man of murder. In his arms he carried a coat and an extra pair of pants. Everything else he left behind. No account survives of the feelings in that dark house, the sorrow and fear, the words spoken and unspoken. It must have felt like a scene from a different time, a man forced into exile, facing a kind of ancient judgment surely not possible in 1955. The history books say he walked six miles in the dark. Nobody knows for sure which direction but when you look at the map, and understand who lived in the houses lining the roads, there’s only one route he could have taken: down the Drew‑Cleveland Road, now the Drew‑Ruleville Road, skirting the edge of Dockery Farms.

I’ve driven that road at night, in a big, modern Chevrolet four‑ wheel‑drive, with my armor of white skin, with a .40‑caliber semi‑ automatic pistol in the glove box, and even then it’s spooky. The darkness of rural Mississippi remains a physical thing, heavy and alive, a sonic experience, too, loud with bugs and birds. There is no safety outside the civilization of headlights. If someone wanted to kill you, there would be nobody to hear you scream. If someone approached, there would be no place to hide. This road was by far Reed’s safest option, lined with poor Black families. He only had two other options to escape. The first, the Drew‑Merigold Road, would have taken him through the only real community of small, poor, white farmers in the Delta. That was suicide. He could have run into the town of Drew. Also suicide. That left Ruleville, which is 6.6 miles from his house and still risky. One of the policemen in the city of Ruleville was J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant’s brother. Reed likely passed his girlfriend Ella Mae Stubbs’s home. He didn’t have time to tell her goodbye.

A car waited in the dark at the end of the road. The driver took Reed north on Highway 61 through Cleveland and Merigold, finally reaching Mound Bayou and safety. Another car awaited him there. The man behind the steering wheel was Medgar Evers. The other passenger was Congressman Diggs. The three men drove north in Evers’s Oldsmobile 88 with a big‑block V‑8, which he had bought specifically to outrun the white terrorists who’d follow and chase him through the backroads of the rural state. His speedometer glowed red whenever he got over sixty miles an hour, which he did as the three men roared toward Memphis Airport. When they arrived, Diggs and Reed went inside the terminal. They probably took the 10:00 a.m. Delta‑C&S 686 from Memphis to Chicago, with a stop in Saint Louis, each leg exactly an hour and nine minutes. That’s three hours with the layover to try to imagine what awaited them when the plane touched down. In Chicago, Diggs took Willie to Congressman William Dawson’s office. Dawson had represented the South Side of Chicago since 1943. An uncle met him up there. Two strangers approached them.

“Willie?” “Willie Reed?”

Both Reed and his uncle felt terror. He’d already been found. The fear eased when the men introduced themselves as Chicago police officers. They’d been assigned to make sure Reed was safe in his new home. Reed struggled to focus as his uncle took him to his mother’s walk‑up apartment at 2103 South Michigan, two blocks from what is now the Marriott Marquis, across the street from the Chess Records studio where the Rolling Stones would one day visit and find their hero Muddy Waters painting the walls of the lobby.

Reporters met Reed there in the first hours of his exile. “Everybody is scared,” he told them. “Why? What did we do?” They asked him about the world he’d left behind.

“I feel kind of lonely for Ella Mae,” he said.

The next morning charitable strangers offered to write blank checks to bring Ella Mae Stubbs to Chicago. Mississippi reporters went out to the Clark Plantation and found her father, Ernest Stubbs, and asked his opinion. He said his daughter barely knew Willie Reed and that his family was perfectly happy in Mississippi.

Willie Reed never saw Ella Mae Stubbs again.

A Jackson Daily News reporter, Bill Spell, flew up to Chicago in a state‑owned airplane to “interview” him. The whole point was to let Willie know that Mississippi could reach him anytime it wanted. Spell would confess later in life that Senator Eastland’s office was actively digging up dirt on the Till family and actually delivering prewritten hatchet jobs to the Jackson paper where he worked. The reporter, a member of the National Guard, got his commanding officer to approve a military flight to Chicago. Spell found Reed in Michael Reese Hospital, located in Bronzeville on the South Side, with what best can be described as a nervous breakdown. His room was in between the train station where Emmett’s body would arrive and the little piece of sidewalk where Sonny Boy Williamson got murdered as he walked home from a gig. A month later, Reed swallowed his fear and returned to Mississippi to testify in Leflore County as a grand jury debated indicting Milam and Bryant for kidnapping. He told his story and flew back to Chicago. The grand jury declined to bring charges, just as the jury in Sumner had acquitted Milam and Bryant, and with that the legal proceedings in the case of Emmett Till ended.

Reed changed his name to Willie Louis soon after. That had been his father’s last name and he wanted to be anonymous again. Every day he went to work as a surgical technician in a South Side hospital, located between Michelle Obama’s childhood home and the house of poet Gwendolyn Brooks. Mamie Till-Mobley, Simeon Wright, and Wheeler Parker all lost touch with him and thought he’d been killed. Willie Louis vanished into working-class Chicago. He would go many years before telling another person about what he’d heard that morning inside Leslie Milam’s barn.

From “The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi” by Wright Thompson. Copyright © 2024 by Wright Thompson. Published by permission of Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Get the book here:

“The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi” by Wright Thompson

Buy locally from Bookshop.org

For more info:

CBS News

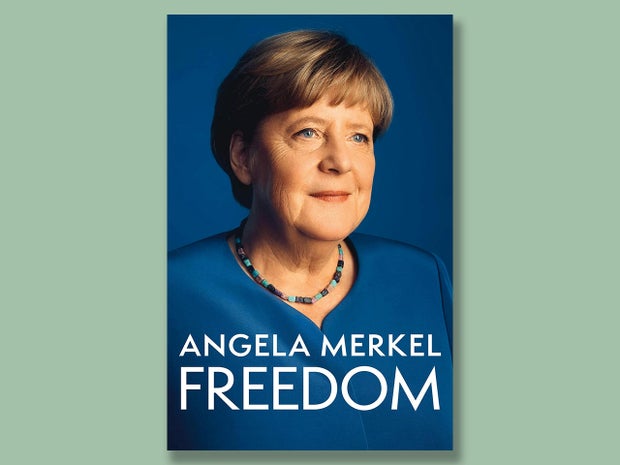

Book excerpt: “Freedom: Memoirs 1954-2021” by Angela Merkel

St. Martin’s Press

We may receive an affiliate commission from anything you buy from this article.

In “Freedom: Memoirs 1954-2021” (published by St. Martin’s Press), former German Chancellor Angela Merkel writes about two lives: her early years growing up under a dictatorship in East Germany, and her years as leader of a nation reunited following the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Read an excerpt below, and don’t miss Mark Phillips’ interview with Angela Merkel on “CBS Sunday Morning” December 1!

“Freedom: Memoirs 1954-2021” by Angela Merkel

Prefer to listen? Audible has a 30-day free trial available right now.

Prologue

This book tells a story that will not happen again, because the state I lived in for thirty-five years ceased to exist in 1990. If it had been offered to a publishing house as a work of fiction, it would have been turned down, someone said to me early in 2022, a few weeks after I stepped down from the office of federal chancellor. He was familiar with such issues, and was glad that I had decided to write this book, precisely because of its story. A story that is as unlikely as it is real. It became clear to me: telling this story, drawing out its lines, finding the thread running through it, identifying leitmotifs, could also be important for the future.

For a long time I couldn’t imagine writing such a book. That first changed in 2015, at least a little. Back then, in the night between September 4 and 5, I had decided not to turn away the refugees coming from Hungary at the German-Austrian border. I experienced that decision, and above all its consequences, as a caesura in my chancellorship. There was a before and an after. That was when I undertook to describe, one day when I was no longer chancellor, the sequence of events, the reasons for my decision, my understanding of Europe and globalization bound up with it, in a form that only a book would make possible. I didn’t want to leave the further description and interpretation just to other people.

But I was still in office. The 2017 Bundestag election followed, along with my fourth period of office. In its last two years the containment of the COVID-19 pandemic was the predominant theme. The pandemic, as I said publicly on several occasions, made huge demands on democracy, on a national, European, and global level. This also prompted me to broaden my outlook and not only write about refugee policy. If I was going to do it at all, I had to do it properly, I said to myself, and if I was, then I would do it with Beate Baumann. She has been advising me since 1992, and is an eyewitness.

I stepped down from office on December 8, 2021. After sixteen years I left it, as I said at the Bundeswehr’s Military Tattoo in my honor a few days before, with joy in my heart. By the end I had in fact longed for that moment. Enough was enough. Now it was time to take a break and rest for a few months, leave the frantic world of politics behind me, to begin a new life in the spring, slowly and tentatively, still a public life, but not an active political one, find the right rhythm for public appearances—and write this book. That was the plan.

Then came February 24, 2022, Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

It was immediately clear that writing this book as if nothing had happened was completely out of the question. The war in Yugoslavia at the beginning of the 1990s had already shaken Europe to its core. But the Russian attack on Ukraine was a greater threat. It was a breach of international law that shattered the European peace which had prevailed since the Second World War and was based on the preservation of the territorial integrity and sovereignty of its states. Profound disillusionment followed. I will write about that too. But this is not a book about Russia and Ukraine. That would be a different book.

Instead I would like to write the story of my two lives, the first up to 1990 in a dictatorship and the second since 1990 in a democracy. At the moment when the first readers hold this book in their hands, the two halves are of more or less equal length. But in fact, of course, these are not two lives. In fact they are one life, and the second part cannot be understood without the first.

How did it happen that, after spending the first thirty-five years of her life in the GDR, a woman was able to take over the most powerful office that exists in the Federal Republic of Germany and hold it for sixteen years? And that she left it again without having to step down during a period of office or being voted out? What was it like to grow up in East Germany as the child of a pastor, and study and work under the conditions of a dictatorship? What was it like to experience the collapse of a state? And to be suddenly free? That’s the story I want to tell.

Of course, my account is deeply subjective. At the same time, I have aimed for honest self-reflection. Today, I will identify my misjudgments and defend the things I think I got right. But this is not a complete account of everything that happened. Not everyone who might have expected, or who might have been expected, to appear in these pages will do so. For that I request understanding. My goal is to establish some points of focus with which I attempt to tame the sheer mass of material, and allow people to understand how politics works, what principles and mechanisms there are—and what guided me.

Politics isn’t witchcraft. Politics is made by people, people with their influences, their experiences, vanities, weaknesses, strengths, desires, dreams, convictions, values, and interests. People who need to fight for majorities in a democracy if they want to make things happen.

We can do this—Wir schaffen das. Throughout the whole of my political career, no phrase has been thrown back at me with quite such virulence as this one. No phrase has been so polarizing. For me, however, it was quite an ordinary phrase. It expressed an attitude. Call it trust in God, caution, or simply a determination to solve problems, to deal with setbacks, get over the lows and come up with new ideas. “We can do this, and if something stands in our way it has to be overcome, it has to be worked on.” That was how I put it in my summer press conference on August 31, 2015. That was how I did politics. It’s how I live. It’s also how this book came about. With this attitude, which is also something learned, everything is possible, because it isn’t only politics that contributes to it—every individual person has a part to play.

Angela Merkel

With Beate Baumann

Berlin, August 2024

From “Freedom: Memoirs 1954-2021” by Angela Merkel. Copyright © 2024 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.

Get the book here:

“Freedom: Memoirs 1954-2021” by Angela Merkel

Buy locally from Bookshop.org

For more info:

CBS News

LGBTQ Americans and the 2024 election: “I don’t feel welcome here.”

Lucian Holness woke up to a daunting reality on Nov. 6. Acute stress led to the mix of emotions that struck the transgender marketing manager as they learned President-elect Donald Trump — never a reliable ally to the LGBTQ community and an increasingly hostile figure for transgender Americans — had won a second term in the White House.

“I went into this election fully expecting Trump to win,” said Holness, who lives in New Jersey and began to medically transition during the pandemic, an experience they called “liberating” and “amazing” after a long time spent “feeling like something was wrong.”

Assuming Trump would take the presidency again was a self-preservation tactic, Holness told CBS News but it did not necessarily soften the blow.

“Maybe I thought it would be a closer race than it was. And just seeing how many states we were losing, the immense way that we lost … that really destroyed me,” Holness said. “And for several days after I had no hope in humanity.”

After the election, commentators and analysts suggested Trump’s decisive victory against Vice President Kamala Harris was broad evidence of a thirst for economic change across the bright red map of the country. To win, he had punctured the Democratic “blue wall” and flipped all seven battleground states, with CBS News exit polls indicating he had received support from more of the electorate than ever.

LGBTQ voters were among the only demographic groups that did not stray toward Trump when they cast ballots in the presidential contest this year. Black women also overwhelmingly backed Harris at the polls.

“Black voters and queer voters understood the assignment in this election, and our assignment was to defeat the great threat to our safety and freedom that Trump poses, so that we can fight for what all of us need to be safe and free,” said Melanie Willingham-Jaggers, the executive director of GLSEN, an LGBTQ advocacy group focused on supporting and educating young people. Willingham-Jaggers identifies as nonbinary and queer.

The LGBTQ community has historically voted Democrat but unlike most other demographic trends this year, LGBTQ support for the party’s presidential nominee rose substantially sa 2020. CBS News’ national exit polls showed 86% of people who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender voted for Harris, while just 13% voted for Trump. Echoing most Harris voters, a majority of LGBTQ people said they feared what could happen during another Trump presidency.

People in the LGBTQ community told CBS News they see the recurrence of Trumpism as a tangible affront to their basic human rights. The implications feel particularly urgent to transgender Americans, whom the president-elect and his affiliates categorically targeted throughout the campaign.

“Unfortunately, these individuals are sadly misinformed,” said Karoline Leavitt, a spokesperson for the Trump-Vance transition team, in a statement to CBS News. “President Trump campaigned on being a president for ALL Americans and will unify our country through great success.”

“I don’t feel welcome here”

The Trump campaign ran advertisements attacking trans people for months ahead of Election Day, in a move that likely cost at least tens of millions of dollars. Criticized for scapegoating, one TV ad bore a tagline interpreted as an attempt to sow division: “Kamala is for they/them. President Trump is for you.”

The advocacy organization GLAAD counted 225 defined attacks on the LGBTQ community by Trump during his first White House term and latest presidential campaign, in terms of policy decisions and rhetoric, which transgender Americans and others who are LGBTQ told CBS News is damaging on its own. The Trevor Project saw a 700% spike in crisis calls throughout the day after the election, and research from the organization found recent politics negatively impacted the well-being of 90% of LGBTQ young people, while anti-trans state legislation in the last year drove up suicide attempts among transgender and nonbinary youth by as much as 72%.

“I don’t feel welcome here,” said Holness.

Although New Jersey is a sanctuary state for LGBTQ rights, and Gov. Phil Murphy last year declared it a safe haven for transgender and nonbinary people seeking gender-affirming care, Holness is still concerned about the ways in which a second Trump administration and Republican Congress could potentially work to break down that refuge.

“What people think being trans is, versus the actual experience of being trans, are so vastly different. And if people would just listen to us, I think they’d be surprised how much we are the same as them,” Holness told CBS News. “It took me a while to take Trump seriously, but after seeing the rise in trans hate crimes, and the rise in anti-trans legislation, the bounty out on trans people just for existing, you know, it’s become really scary.”

Trump’s anti-LGBTQ and specifically anti-trans positions stretch back to his first term in the White House, when he scrubbed federal agency sites of representation and proceeded to roll back protections for LGBTQ people, among other policy decisions that clamped down on their abilities to live and work freely.

But vitriol toward the community became integral to Trump’s politics and his overall public brand during the latest presidential bid.

Health care access under siege

As Trump doubled down on anti-trans rhetoric in his speeches, he backed conservative proposals to restrict access to healthcare for transgender people and punish doctors who give minors gender-affirming care.

“The number one issue, of the many that the trans people I spoke with are worried about, is access to the health care that we need to live. This is not an abstraction. It is not a culture war. It is not a political football,” said Gillian Brandstetter, a communications strategist at the American Civil Liberties Union. “It is very much a problem of material need. Can we access hormone therapy? Can we maintain our relationship with our doctors? Can we maintain our insurance coverage?”

Trump pushed during his last administration to federally redefine gender along binary lines that would exclude transgender identities, effectively denying trans people legal recognition and upholding an outdated characterization of “biological sex,” even though the medical field has expanded its view of the spectrum of gender identity. Renewed promises made by the campaign this year are fueling panic that he will attempt to implement it nationally again.

Ryan Lyman, a trans college student in New York City who volunteered for the Harris campaign and said he has “passing privilege” after beginning hormone therapy at 17 and undergoing top surgery, told CBS News trans people elsewhere in the country are preparing for the worst case scenario. “Passing privilege” in this instance means Lyman may avoid some of the prejudice other transgender people face if he is publicly perceived to be a cisgender man.

“I’ve seen a lot of people on the Internet lately who are going back to their assigned gender presentation,” Lyman said. “There is a part of the community that lives in the Deep South, in red states, who have to go stealth for their own safety. And I do not judge them at all.”

A decision that could potentially work to protect certain trans rights before Inauguration Day is the outcome of United States v. Skrmetti, a landmark case set to go before the Supreme Court in December where justices will hear a challenge to Tennessee’s ban on gender-affirming health care for transgender people younger than 18. The decision could have wide-ranging impacts at a time where almost half of U.S. states have enacted laws to limit access to various aspects of gender-affirming care, like hormones, puberty-blocking drugs or surgery.

An uncertain future

Many LGBTQ people are anxious about how Trump could alter fundamental parts of their lives, out in the world and at home.

A growing number of transgender social media users have now spent the better part of a month sharing guidance on how to update licenses, passports and other legal documents to reflect their names and pronouns. LGBTQ couples told CBS News they are having conversations about whether they should rush to get married before January’s inauguration and what family planning might look like once Trump is sworn in.

Lee Robinson, a comedian moving from Denver to New York City, said they were already considering some of those big questions within days of the election. They had started to discuss their options with their girlfriend, too.

“It’s not just marriage, it’s parentage and fertility stuff, and queer adoption,” said Robinson. “It just totally throws off our ability to plan for our futures when this kind of thing happens.”

Everyone who spoke to CBS News for this story shared concerns about losing discrimination protections under a second Trump administration. They also wonder what it would mean if the Supreme Court’s 2015 marriage equality ruling came under review and marriage rights, like abortion rights, were returned to the states.

An updated policy rundown on Trump’s 2024 campaign website called Agenda 47 offers a blueprint of his “20 Core Promises To Make America Great Again.” Among the items on that list, Trump pledges to “keep men out of women’s sports” and cut federal funding for schools “pushing critical race theory, radical gender ideology, and other inappropriate racial, sexual, or political content on our children.”

These items echo GOP state lawmakers and government leaders who have sought to bar trans youth from athletic teams that align with their gender identities and ban LGBTQ and racial identity-focused lesson plans and books from school curriculum. The First Amendment’s freedom of speech and religion clauses have been used in high-profile court cases to justify anti-LGBTQ discrimination.

They are not just concepts. Anti-LGBTQ doctrines embraced at Republican rallies have in recent years been codified across the country, keeping transgender children off of sports teams and away from bathrooms aligned with their gender identity. In Florida, laws have been passed to take transgender-focused curriculum out of schools; a legal settlement earlier this year clarified that students and teachers would be able to discuss gender identity as long as it’s not part of the curriculum.

Capitol Hill is not immune, as Rep.-elect Sarah McBride, a Delaware Democrat set to become the first openly transgender person in Congress, faced a swift Republican-led attempt after her trailblazing win to restrict her restroom use in the Capitol Complex.

“It’s dehumanizing people,” said Sarah Kate Ellis, the president and CEO of the advocacy organization GLAAD. “They want to treat us as second-class citizens, question our dignity and respect.”

Ellis said measurable repercussions in the balance, like medical coverage and equality under the law, are joined by intangible consequences that could trickle down generations.

“I think of my kids, as my wife and I’s marriage is under fire, but our neighbors’ marriage isn’t under fire. It’s awful when you think about that,” she shared. “So, my kids, in their understanding, see us as less than the family next door because they have two moms versus a mom and a dad, or a single mom. I just think all these are their culture wars, not ours.”

Project 2025

Experts often attribute the intensification of Trump’s anti-LGBTQ platform to his ties with right-wing religious groups like the Heritage Foundation, an organization with a long history of espousing anti-LGBTQ laws that helmed the presidential transition proposal Project 2025.

Project 2025 is a 900-page policy handbook developed by a team linked to more than 100 conservative groups, to which Trump had denied connections, though he is hiring several of its architects to fill key staff positions in the next administration. The book calls for an overhaul of the federal government to “restore family as the centerpiece of American life.” Its socio-political vision for how to do that, introduced on the first page of Project 2025, directs government officials to reject transgender people and LGBTQ identities across the board.

“The next conservative President must make the institutions of American civil society hard targets for woke culture warriors. This starts with deleting the terms sexual orientation and gender identity (“SOGI”), diversity, equity, and inclusion (“DEI”), gender, gender equality, gender equity, gender awareness, gender-sensitive, abortion, reproductive health, reproductive rights, and any other term used to deprive Americans of their First Amendment rights out of every federal rule, agency regulation, contract, grant, regulation, and piece of legislation that exists,” the document states, at the outset of its opening chapter.

Although Trump attempted to distance himself from Project 2025 on the campaign trail, even going so far as to call some of its proposals “abysmal,” the blueprint is compatible with the Republican Party agenda. But at the same time, Trump also plans to nominate Scott Bessent to be treasury secretary. He’s a billionaire and former George Soros hedge fund manager and if confirmed, he’d be the first openly gay person to serve in this role.

“We should absolutely take Trump at his word,” said Willingham-Jaggers, of GLSEN. “We should take Project 2025 at its word. We should expect a full court press to get everything outlined in Project 2025, created into policy and enacted as the starting point, not the end point, as the starting point. That’s part one. That’s what I’m concerned about.”