CBS News

A new mom died after giving birth at a Boston hospital. Was corporate greed to blame?

Nabil Haque said he can still remember the moment his wife Sungida Rashid first held their baby daughter in her arms after giving birth at Boston’s St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center last October.

“It was a beautiful moment,” Haque told CBS News chief medical correspondent Dr. Jon LaPook, in his first television interview. “I wasn’t expecting it to be this blissful.”

The bliss was short-lived. In the hours after delivery, Rashid experienced a cascade of complications at a hospital that was unexpectedly ill-prepared for her urgent need, and was transferred to another hospital, where she died. Her death has triggered a fresh wave of public scrutiny into the mounting patient risks and health care compromises that have surfaced under hospitals owned by private equity-backed companies.

“They’ve taken money away from these hospitals that provide needed care and they’re using that money to line their own pockets.” Massachusetts Gov. Maura Healey told CBS News. “I’m disgusted. It’s selfish. It’s greed.”

The hospital where Rashid gave birth, St. Elizabeth’s, is one of dozens of hospitals across the U.S. acquired in the past 15 years by a company called Steward Health Care. With hundreds of millions of dollars in backing from private equity giant Cerberus, Steward started buying up Massachusetts hospitals in 2010 and now owns 33 hospitals across 8 states.

Adam Glanzman/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The Dallas-based health care company has been one focus of a year-and-a-half-long CBS News investigation revealing how private equity investors have siphoned hundreds of millions of dollars from community hospitals with devastating public health consequences. Last April, CBS News found Steward redirected money away from hospital operations by selling off the real estate of San Antonio’s Texas Vista Medical Center before closing the facility altogether.

A spokesperson for Steward told CBS News company executives always put patients first and said they “deny that any other considerations were placed ahead of that guiding principle.” In an earlier statement, the spokesperson said Steward “has actively and meaningfully invested” in its hospital system since its formation, including in Massachusetts, where it took over hospitals that were “failing” and “about to close.”

“Steward’s investment has taken the form of facility upgrades, equipment, technology, and other meaningful improvements,” the spokesperson wrote.

Yet records reviewed by CBS News showed Steward hospitals around the country with a trail of unpaid bills, at times risking a shortage of potentially life-saving supplies. That appears to be what happened at St. Elizabeth’s last October, where medical staff says a device that could have stopped the bleeding in Rashid’s liver was repossessed by the manufacturer weeks earlier.

After giving birth, Rashid experienced bleeding from her uterus, followed by pain around the back of her rib cage. Doctors sent her for an emergency CT scan and then rushed her to the emergency room where, Haque said, they found bleeding in her liver. Hours later, Rashid died during surgery at a second hospital, a tragedy first reported by the Boston Globe,

Courtesy of Nabil Haque

Rashid’s death is now the subject of a state investigation. Haque says doctors told him they wanted to use a device called an embolization coil to stop the bleeding from his wife’s liver. He said when St. Elizabeth’s didn’t have the coil, she was transferred to the second hospital.

“An hour later, she had another cardiac arrest,” Haque said. “They couldn’t revive her. It was shocking. I said, ‘Well, what exactly happened?'”

In a complaint filed to Massachusetts’ health department obtained by CBS News, health care workers at St. Elizabeth’s said the manufacturer had come to “retrieve any coils at the hospital” weeks before because Steward hadn’t paid its bills. According to a lawsuit filed last October by the manufacturer, Steward owed about $2.5 million in unpaid bills.

Steward declined to comment on Rashid’s death, citing privacy concerns. The incident has touched off a wave of recriminations in Massachusetts, where Steward owns nine hospitals, including St. Elizabeth’s. Healey called her death “outrageous,” and her administration is looking at whether her death was preventable.

“It underscores what has been happening out here with Steward,” said Healey. ” If you are about cutting corners in furtherance of making money, people are going to get hurt. That’s wrong. That needs to change.”

Concern about hospitals closing

In December, Steward informed health officials in Massachusetts that it would be closing New England Sinai in Stoughton, another of its hospitals in the state. The announcement has set off statewide fears about the company’s financial situation and whether it would be shuttering more hospitals.

“It’s a catastrophic situation in our state,” said emergency room nurse Kathy Reardon, an official with the Massachusetts Nurses Association, a union that represents health care workers at Steward’s hospitals in the state.

Reardon said Steward’s hospitals typically serve low-income communities and patients without a primary care doctor who end up using the emergency room for their health needs.

“If any of these hospitals were to close, it would be an astronomically tragic situation for all the citizens of Massachusetts,” she said.

In February, a Steward executive sent a message informing staff the company had secured financing “to help stabilize” hospital operations, and, in a statement, a company spokesperson told CBS News it has no plans to close any additional hospitals.

Healey said Steward’s failures have prompted her to install monitors — staff from the state’s health department — inside each of Steward’s hospitals to try to ensure patient safety. She said she believes Steward should no longer be operating in Massachusetts. “They’ve taken too much from too many,” Healey said “The sooner Steward is out of our state, the better.”

Financial questions — and a $40 million yacht

In a statement to CBS News, a Steward spokesperson said that the company had invested about $2 billion in the hospitals it has acquired, including propping up the employee pension fund for employees at its Massachusetts hospitals, which was underfunded by hundreds of millions of dollars when Steward acquired them.

The company has blamed its current financial woes on the pandemic and low reimbursement rates from Medicare and Medicaid services.

In a lengthy interview with CBS News, Healey called Steward’s justification “hogwash.” Instead, she accused Steward executives of driving the company deep into debt while enriching themselves — all at the public’s expense.

“The game was, come to Massachusettts, make some investments and then begin to suck out as much as you can in terms of profits,” she said.

Cerberus, the private equity firm, shed its stake in Steward by January 2021, after making an $800 million profit in a decade, according to a report from Bloomberg. Financial records show Steward has also sold off more than $1 billion of its hospitals’ land and buildings since 2016 to Medical Properties Trust, which has made a business of buying up hospital real estate from private equity investors.

Last year, CBS News reported on Prospect Medical, another private equity-backed chain, whose owners sold off the real estate of a group of suburban Pennsylvania hospitals to cover the debt they incurred when they paid themselves hundreds of millions of dollars out of the company’s coffers.

The financial moves, though legal, ultimately spelled doom for the century-old Delaware County Memorial Hospital, which was forced to shut its doors after Pennsylvania’s health department deemed the facility inadequately staffed.

Angela Neopolitano, who worked at Delaware County Memorial for 41 years, says, before the closure, the hospital was dismantled piece by piece, leading to longer waits in the emergency room and forcing staff to transfer more patients to other hospitals.

“They kept on cutting services,” Neopolitano said. “Things wouldn’t get fixed. Our elevator in the back of the emergency room had been broken for over a year. When they closed the ICU, that was the knife in my heart.”

A filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission from 2021 shows Steward’s owners also paid themselves millions in dividends. Around the same time, Steward CEO Ralph de la Torre acquired a 190-foot yacht estimated to be worth $40 million.

superyachtfan

In an email to CBS News, Steward confirmed de la Torre owned the yacht. Reports about the vessel have been particularly galling to health care workers on the front lines of Steward’s hospitals.

Michael Nagle/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Respiratory therapist Jessica Carrasco worked at Texas Vista Medical Center, Steward’s San Antonio hospital, for eight years. She said, before the company shut the hospital down last May, there was a shortage of tubing for respiratory masks.

“Coordinators were having to phone a friend to let us borrow, you know, a cup of sugar,” Carrasco said.

At Steward’s Massachusetts hospitals, CBS News found at least 16 vendors weren’t paid on time, including a dialysis company that provided life-saving services. Reardon said the supply shortages were unlike anything she’s experienced in her 35 years of nursing.

“It’s unacceptable to us,” she said. “They pick and choose who to pay and what supplies to get.”

A family’s loss: “It’s just still surreal”

Sungida Rashid and Nabil Haque had come to Boston earlier in 2023 for Haque’s postdoctoral program. Haque told us his wife’s smile and sense of humor could light up a room.

“The laugh was, you know, contagious, and you could hear it from a different apartment, but that’s something I really liked about her,” Haque said. “It’s just still surreal, she’s not here.”

Haque said he was angry when he first learned from a Globe reporter that the hospital’s embolization coil had been repossessed. Now, he says he is trying to focus on the small milestones in his daughter’s life instead of wondering whether his wife would still be here if the couple didn’t deliver at a Steward hospital.

“I’m looking forward to her starting to walk and eat solid food, and I’m not planning anything about myself,” said Haque, who spoke with CBS News from his parents’ home in Bangladesh. “A lot of my plans are now buried with Sungida.”

CBS News

In praise of Seattle-style teriyaki

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

Gazan chefs cook up hope and humanity for online audience

Renad Atallah is an unlikely internet sensation: a 10-year-old chef, with a repertoire of simple recipes, cooking in war-torn Gaza. She has nearly a million followers on Instagram, who’ve witnessed her delight as she unpacks parcels of food aid.

CBS News

We interviewed Renad via satellite, though we were just 50 miles away, in Tel Aviv. [Israel doesn’t allow outside journalists into Gaza, except on brief trips with the country’s military.]

“There are a lot of dishes I’d like to cook, but the ingredients aren’t available in the market,” Renad told us. “Milk used to be easy to buy, but now it’s become very expensive.”

I asked, “How does it feel when so many people like your internet videos?”

“All the comments were positive,” she said. “When I’m feeling tired or sad and I want something to cheer me up, I read the comments.”

We sent a local camera crew to Renad’s home as she made Ful, a traditional Middle Eastern bean stew. Her older sister Noorhan says they never expected the videos to go viral. “Amazing food,” Noorhan said, who added that her sibling made her “very surprised!”

After more than a year of war, the Gaza Strip lies in ruins. Nearly everyone has been displaced from their homes. The United Nations says close to two million people are experiencing critical levels of hunger.

Hamada Shaqoura is another chef showing the outside world how Gazans are getting by, relying on food from aid packages, and cooking with a single gas burner in a tent.

Shaqoura also volunteers with the charity Watermelon Relief, which makes sweet treats for Gaza’s children.

In his videos online, Shaqoura always appears very serious. Asked why, he replied, “The situation does not call for smiling. What you see on screen will never show you how hard life is here.”

Before dawn one recent morning in Israel, we watched the UN’s World Food Program load nearly two dozen trucks with flour, headed across the border. The problem is not a lack of food; the problem is getting the food into the Gaza Strip, and into the hands of those who desperately need it.

The UN has repeatedly accused Israel of obstructing aid deliveries to Gaza. Israel’s government denies that, and claims that Hamas is hijacking aid.

“For all the actors that are on the ground, let the humanitarians do their work,” said Antoine Renard, the World Food Program’s director in the Palestinian territories.

I asked, “Some people might see these two chefs and think, well, they’re cooking, they have food.”

“They have food, but they don’t have the right food; they’re trying to accommodate with anything that they can find,” Renard said.

Even in our darkest hour, food can bring comfort. But for many in Gaza, there’s only the anxiety of not knowing where they’ll find their next meal.

For more info:

Story produced by Mikaela Bufano. Editor: Carol Ross.

See also:

“Sunday Morning” 2024 “Food Issue” recipe index

Delicious menu suggestions from top chefs, cookbook authors, food writers, restaurateurs, and the editors of Food & Wine magazine.

CBS News

A study to devise nutritional guidance just for you

It’s been said the best meals come from the heart, not from a recipe book. But at this USDA kitchen, there’s no pinch of this, dash of that, no dollops or smidgens of anything. Here, nutritionists in white coats painstakingly measure every single ingredient, down to the tenth of a gram.

Sheryn Stover is expected to eat every crumb of her pizza; any tiny morsels she does miss go back to the kitchen, where they’re scrutinized like evidence of some dietary crime.

Stover (or participant #8180, as she’s known) is one of some 10,000 volunteers enrolled in a $170 million nutrition study run by the National Institutes of Health. “At 78, not many people get to do studies that are going to affect a great amount of people, and I thought this was a great opportunity to do that,” she said.

CBS News

It’s called the Nutrition for Precision Health Study. “When I tell people about the study, the reaction usually is, ‘Oh, that’s so cool, can I do it?'” said coordinator Holly Nicastro.

She explained just what “precise” precisely means: “Precision nutrition means tailoring nutrition or dietary guidance to the individual.”

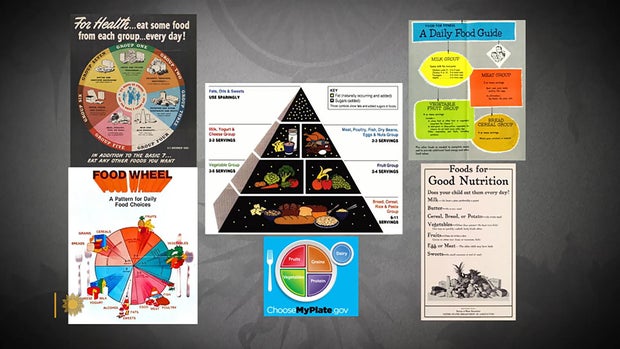

The government has long offered guidelines to help us eat better. In the 1940s we had the “Basic 7.” In the ’50s, the “Basic 4.” We’ve had the “Food Wheel,” the “Food Pyramid,” and currently, “My Plate.”

CBS News

They’re all well-intentioned, except they’re all based on averages – what works best for most people, most of the time. But according to Nicastro, there is no one best way to eat. “We know from virtually every nutrition study ever conducted, we have inner individual variability,” she said. “That means we have some people that are going to respond, and some people that aren’t. There’s no one-size-fits-all.”

The study’s participants, like Stover, are all being drawn from another NIH study program called All Of Us, a massive undertaking to create a database of at least a million people who are volunteering everything from their electronic health records to their DNA. It was from that All of Us research that Stover discovered she has the gene that makes some foods taste bitter, which could explain why she ate more of one kind of food than another.

Professor Sai Das, who oversees the study at Tufts University, says the goal of precision nutrition is to drill down even deeper into those individual differences. “We’re moving away from just saying everybody go do this, to being able to say, ‘Okay, if you have X, Y and Z characteristics, then you’re more likely to respond to a diet, and somebody else that has A, B and C characteristics will be responding to the diet differently,'” Das said.

It’s a big commitment for Stover, who is one of 150 people being paid to live at a handful of test sites around the country for six weeks – two weeks at a time. It’s so precise she can’t even go for a walk without a dietary chaperone. “Well, you could stop and buy candy … God forbid, you can’t do that!” she laughed.

While she’s here, everything from her resting metabolic rate, her body fat percentage, her bone mineral content, even the microbes in her gut (digested by a machine that essentially is a smart toilet paper reading device) are being analyzed for how hers may differ from someone else’s.

Nicastro said, “We really think that what’s going on in your poop is going to tell us a lot of information about your health and how you respond to food.”

CBS News

Stover says she doesn’t mind, except for the odd sounds the machine makes. While she is a live-in participant, thousands of others are participating from their homes, where electronic wearables track all kinds of health data, including special glasses that record everything they eat, activated when someone starts chewing. Artificial intelligence can then be used to determine not only which foods the person is eating, but how many calories are consumed.

This study is expected to be wrapped up by 2027, and because of it, we may indeed know not only to eat more fruits and vegetables, but what combination of foods is really best for us. The question that even Holly Nicastro can’t answer is, will we listen? “You can lead a horse to water; you can’t make them drink,” she said. “We can tailor the interventions all day. But one hypothesis I have is that if the guidance is tailored to the individual, it’s going to make that individual more likely to follow it, because this is for me, this was designed for me.”

For more info:

Story produced by Mark Hudspeth. Editor: Ed Givnish.

“Sunday Morning” 2024 “Food Issue” recipe index

Delicious menu suggestions from top chefs, cookbook authors, food writers, restaurateurs, and the editors of Food & Wine magazine.