CBS News

Supreme Court grapples with online First Amendment rights as social media teems with misinformation

As big tech firms wrestle with how to keep false and harmful information off their social networks, the Supreme Court is wrestling with whether platforms like Facebook and Twitter, now called X, have the right to decide what users can say on their sites.

The dispute centers on a pair of laws passed in the red states of Florida and Texas over the question of First Amendment rights on the internet. The Supreme Court is considering whether the platforms are like newspapers, which have free speech rights to make their own editorial decisions, or if they’re more like telephone companies, that merely transmit everyone’s speech.

If the laws are upheld, the platforms could be forced to carry hate speech, and false medical information, the very content most big tech companies have spent years trying to remove through teams of content moderators. But in the process, conservatives claim that the companies have engaged in a conspiracy to suppress their speech.

As in this case: a tweet in 2022 from Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene falsely claiming that there were…

“Extremely high amounts of COVID vaccine deaths.”

Twitter eventually banned Greene’s personal account for “multiple violations” of its COVID policy.

Facebook and YouTube also removed or labeled posts they deemed “misinformation.”

Confronted with criticisms from conservatives like Congressman Jim Jordan, that the social media companies were censoring their views, and because of cost-costing, platforms began downsizing their fact checking teams.

60 Minutes

So today, social media is teeming with misinformation. Like these posts suggesting tanks are moving across the Texas-Mexico border. But it’s actually footage from Chile.

These are AI-generated images of – well, see for yourself.

With social media moderation teams shrinking, a new target is misinformation academic researchers who began working closely with the platforms after evidence of Russian interference online in the 2016 election.

Lesley Stahl: Are researchers being chilled?

Kate Starbird: Absolutely.

Kate Starbird is a professor at the University of Washington, a former professional basketball player, and a leader of a misinformation research group created ahead of the 2020 election.

Kate Starbird: We were very specifically looking at misinformation about election processes, procedures, and election results. And if we saw something about that, we would pass it along to the platforms if we thought it violated their– one of their policies.

Here’s an example: a November 2020 tweet saying that election software in Michigan “switched 6,000 votes from Trump to Biden.”

The researchers alerted Twitter that then decided to label it with a warning.

Lesley Stahl: I understand that some of the researchers, including you, have– had some threats against them death threats.

Kate Starbird: I have received one. Sometimes they’re threats with something behind them. And sometimes they are just there to make you nervous and uncomfortable. And it’s hard to know the difference.

Lesley Stahl: This campaign against you is meant to discredit you. So we won’t believe you.

Kate Starbird: Absolutely. It’s interesting that the people that pushed voter fraud lies are some of the same people that are trying to discredit researchers that are trying to understand the problem.

Lesley Stahl: Did your research find that there was more misinformation spread by conservatives?

Kate Starbird: Absolutely. I think– not just our research, research across the board, looking at the 2020 election found that there was more misinformation spread by people that were supporters of Donald Trump or conservatives. And the events of January 6th kind of underscore this.

Kate Starbird: The folks climbing up the Capitol Building were supporters– of Donald Trump. And they were– they were misinformed by these false claims. And– and that motivated those actions.

60 Minutes

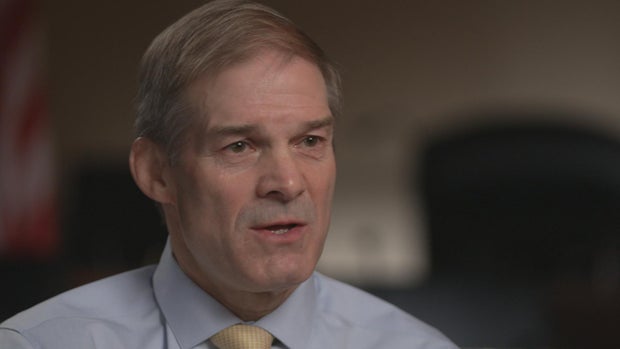

Ohio Republican Congressman Jim Jordan is chairman of the House Judiciary Committee.

Lesley Stahl: So how big a problem is mis and disinformation on the web?

Rep. Jim Jordan: Well, I’m sure there’s some. But I think, you know– our concern is the bigger problem of the attack on First Amendment liberties.

Congressman Jordan’s Judiciary Committee produced a report that concluded there’s a “censorship industrial complex” where the federal government and tech companies colluded with academic researchers to disproportionately silence conservatives, which Kate Starbird vigorously denies.

But Congressman Jordan says her group unfairly flagged posts like this tweet by Newt Gingrich:

“Pennsylvania democrats are methodically changing the rules so they can steal the election”

He complains that government officials put pressure on social media companies directly –

Rep. Jim Jordan: A great example, 36 hours into the Biden administration, the– the Biden White House sends– a email to Twitter and says, “We think you should take down this tweet ASAP.”

Just a call alone from the government, he says, can be unnerving.

Rep. Jim Jordan: You can’t have the government say, “Hey, we want you to do X,” government who has the ability to regulate these private companies, government which has the ability to tax these private companies.

He says that White House email to Twitter involved a tweet from…

Rep. Jim Jordan: Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and everything in the tweet was true.

That tweet implied falsely that baseball legend Hank Aaron’s death was caused by the COVID vaccine.

Lesley Stahl: Did they take it down?

Rep. Jim Jordan: Turned out they didn’t. Thank goodness.

And that post is still up.

Kate Starbird says the social media platforms also often ignored the researchers’ suggestions.

Kate Starbird: The statistics I’ve seen are just for the Twitter platform. But I– my understanding is– is that they’ve responded to about 30% of the things that we sent them. And I think the– on the majority of those, they put labels.

Lesley Stahl: But just a third.

Kate Starbird: Just a third, yeah.

Lesley Stahl: And do you suspect that Facebook was the same?

Kate Starbird: Oh, yeah.

Katie Harbath: These platforms have their own First Amendment rights.

Katie Harbath spent a decade at Facebook where she helped develop its policies around election misinformation. When she was there, she says it was not unusual for the government to ask Facebook to remove content, which is proper, as long as the government is not coercing.

60 Minutes

Katie Harbath: Conservatives are alleging that the platforms were taking down content at the behest of the government which is not true. The platforms made their own decisions. And many times we were pushing back on the government.

Lesley Stahl: Can we talk about a specific case? It’s of Nancy Pelosi. It’s a doctored tape where she’s– she looks drunk.

This was the video of then-House Speaker Pelosi posted to Facebook in 2019, slowed down to make it seem that she was slurring her words.

Lesley Stahl: Did it come down?

Katie Harbath: It did not.

Lesley Stahl: Why?

Katie Harbath: Because it didn’t violate the policies that they had.

Lesley Stahl: So did she put pressure on the company to take it down?

Katie Harbath: She was definitely not pleased.

Lesley Stahl: Is that a yes?

Katie Harbath: Yes. And it really damaged the relationship that the company had with her.

The conservatives’ campaign faced a setback at the Supreme Court on Monday when a majority of the justices seemed poised to reject their effort to limit attempts by the government to influence social media.

The court is deciding, in separate cases, whether the platforms are like news organizations with a First Amendment right to control who and what information appears on their sites.

Congressman Jordan argues that the tech companies shouldn’t remove most of what they call “misinformation.”

Rep. Jim Jordan: I think you let the American people, respect the American people, their common sense, to figure out what’s accurate, what isn’t.

Lesley Stahl: Well, what about this idea that they– the 2020 election was stolen? You think that these companies should allow people to say that and individuals can make up their own mind and that there should be–

Rep. Jim Jordan: I think the American people are smart. Look– I’ve not said that. What I’ve said is there were concerns about the 2020 election. I think Americans agree with that.

Lesley Stahl: No they don’t–

Rep. Jim Jordan: You don’t think they think there were concerns with the 2020 election?

Lesley Stahl: Most people don’t question the result. That’s all I’m saying. They don’t question whether–

Rep. Jim Jordan: Fair enough.

Lesley Stahl: Biden won or not. Right? Right? Most people don’t question

Rep. Jim Jordan: Oh, OK. No–

Lesley Stahl: The outcome.

Rep. Jim Jordan: Right.

X basically did what Jordan proposes. After Elon Musk took over in 2022, most of its fact checkers were fired. Now the site is rife with trash talk and lies. Little would you know that this – said to be footage from Gaza — is really from a video game. Eventually X users added a warning label.

In this post, pictures of real babies killed in Israeli strikes are falsely dismissed as dolls.

Darrell West: The toothpaste is out of the tube and we have to figure out how to deal with the resulting mess.

60 Minutes

Darrell West, a senior fellow of technology innovation at the Brookings Institution, says the clash over “what is true” is fraying our institutions and threatening democracies around the world.

Darrell West: Half of the world is voting this year and the world could stick with democracy or move toward authoritarianism. The danger is disinformation could decide the elections in a number of different countries.

In the U.S., he says, the right wing has been flooding the internet with reams of misleading information in order to confuse the public. And he’s alarmed by the campaign to silence the academic researchers, who have had to spend money and time on demands from Jim Jordan’s Judiciary Committee.

Lesley Stahl: There are people who make the accusation that going after these researchers, misinformation researchers, is tantamount to harassment. And that your goal really is to chill the research.

Rep. Jim Jordan: I find it interesting that you use the word “chill,” because in– in effect, what they’re doing is chilling First Amendment free speech rights. When, when they’re working in an effort to censor Americans, that’s a chilling impact on speech.

Lesley Stahl: They say what you’re doing, they do, is a violation of their First Amendment right.

Rep. Jim Jordan: So us pointing out, us doing our constitutional duty of oversight of the executive branch– and somehow w– (LAUGH) we’re censoring? That makes no sense.

Lesley Stahl: We Americans, we’re looking at the same thing and seeing a different truth.

Rep. Jim Jordan: We might see different things, I don’t– I don’t think you can see a different truth, because truth is truth.

Lesley Stahl: Okay. The– the researchers say they’re being chilled. That’s their truth.

Rep. Jim Jordan: Yeah.

Lesley Stahl: You’re saying they’re not. So what’s the truth?

Rep. Jim Jordan: They can do their research. God bless em’, do all the research you want. Don’t say we think this particular tweet is not true– and– or– or–“

Lesley Stahl: Well, that’s their First Amendment right to say that.

Rep. Jim Jordan: Well, they can say it, but they can’t take it down.

Lesley Stahl: Well, they can’t take it down and they don’t. They just send their information to the companies.

Rep. Jim Jordan: But when they’re coordinating with government, that’s a different animal.

Lesley Stahl: Okay, well, of course, they deny they’re coordinating.

We just went round and round.

Starbird says she and her team feel intimidated by the conservatives’ campaign, so while they will continue releasing their research reports on misinformation, they will no longer send their findings to the social media platforms.

Produced by Ayesha Siddiqi. Associate producer, Kate Morris. Broadcast associates, Wren Woodson and Aria Een. Edited by Matthew Lev.

CBS News

Recall affects roughly 240,000 electric vehicles

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

Law enforcement raises warning over so-called pink cocaine

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

Lowriders shine in New Mexico after perceptions of the cars and their drivers shift

The Merriam Webster dictionary defines lowrider as “a customized car with a chassis that has been lowered so that it narrowly clears the ground.” Lowrider also is used to describe the person driving such a vehicle, and both car and driver have long been potent cultural symbols, especially among Mexican Americans.

In the 1980s and ’90s, many cities passed “anti-cruising” ordinances, because police departments and the public often saw lowriders as menacing; connected to drugs and gangs.

It’s taken decades, but that perception is finally changing, And nowhere is the transformation more pronounced than in the lowrider hotbed of northern New Mexico.

Eppie Martinez: So the ride will be a little bit rough.

Bill Whitaker: That’s OK.

Eppie Martinez: That’s what hydraulics is, it’s– you know–

Bill Whitaker: But– but we look cool.

Eppie Martinez: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, (laugh)

On Good Friday 2024, we’re cruising down Riverside Drive in Española, New Mexico with Eppie Martinez and his family in his 1953 Chevy Bel Air- his pride and joy.

60 Minutes

Eppie Martinez: You gotta have your siren (turns siren on)

Bill Whitaker: Gotta have your siren.

He’s been cruising this road in this vintage car since he was a kid with his dad at the wheel. And Good Friday has long been the day for local lowriders.

Eppie Martinez: This is the grand opening of spring, you know? Everybody looks forward, as you can see today. Oh, my God, it’s gonna be–

Bill Whitaker: It’ll blow my mind.

Eppie Martinez: Definitely.

Martinez is leading a candy-colored caravan of cars from his Viejitos Car Club – that’s “old men” in Spanish. Espanola calls itself the “lowrider capital of the world,” and on Good Friday the Viejitos were joined by lowriders from many other local car clubs for a chrome-and-tailfin celebration of their culture. Some were shining up and staying put to be admired, while others showed off the crazy hydraulic gymnastics lowriders are known for.

Among New Mexico’s lowriders, Eppie Martinez is known as the man who makes cars do that.

Bill Whitaker: So people come to you–

Eppie Martinez: Yes, yes.

Bill Whitaker: –to have the hydraulics put in their cars?

Eppie Martinez: Yes. Yes, yes, exactly. Yeah, exactly.

Bill Whitaker: How many have you done?

Eppie Martinez: Oh, I’ve done over 500 probably. (laugh)

The hydraulics in his own precious ’53 Bel Air are fairly modest.

Eppie Martinez: We got ourselves here something not too much. I got a two pump setup. It’s mostly aircraft.

Bill Whitaker: This is aircraft technology?

Eppie Martinez: Exactly.

Bill Whitaker: In this old car.

Eppie Martinez: Exactly.

Those hydraulic pumps, designed to operate aircraft flaps and landing gear, are controlled by switches at the driver’s seat.

Eppie Martinez: So that’s really– that’s all it really does. It doesn’t go too much, ’cause, you know, I don’t wanna hurt it. You know what I mean?

Bill Whitaker: Yeah.

Over the years, Martinez has installed hydraulics that seem guaranteed to hurt cars, turning them into what lowriders call hoppers that drew competitors and crowds to this Espanola parking lot on Good Friday, to see who could jump highest.

60 Minutes

Whether they hopped to the sky or sat ever-so-low to the ground, each lowrider we saw that day seemed to say “here I am!”

Delubina Montoya: It’s an expression of who you are. So it’s kind of an extension of your personality.

Delubina and Eric Montoya were there with their 1947 Chevrolet Fleetmaster convertible.

Delubina Montoya: It’s sleek. It’s classic. It’s beautiful. It’s kinda me. (laughter)

Eric Montoya: It’s round. It’s shapey. It’s shiny.

Delubina Montoya: So, see, it’s me. (laughter)

Patricia Trujillo: Lowriders are all about that, right? They’re– the car amongst cars. They’re gonna be the one that pops.

Patricia Trujillo is an Espanola native, a college professor, and deputy cabinet secretary of New Mexico’s Department of Higher Education. She told us the roots of the lowrider culture here stretch back to just after World War II.

Patricia Trujillo: You had many– Mexican Americans going into the Army, and then coming back and still being treated as second-class citizens. And so– a lot of those—people basically created this counter-culture to be able to speak back and say, “We belong here, too. “It’s almost like a saunter or a swagger in vehicle form, right?

Bill Whitaker: It’s sort of like embracing the Americanness, the car culture, but making it your own and saying, “I am part of America, but I’m not part of this mainstream. I am doing my own thing here.”

Patricia Trujillo: Yeah. And we ARE our own thing.

Bill Whitaker: So low and slow, instead of fast and furious?

Patricia Trujillo: Yes, absolutely.

These are Buicks and Pontiacs and Chevys from the glory days of Detroit…

…customized with elaborate interiors, intricate engraving, and kaleidoscopic colors in the paint jobs. The over-the-top style isn’t for everyone, but these cars are all labors of love, whether do-it-yourself jobs or those restored by professionals for tens of thousands of dollars.

Rob Vanderslice: This ends up about 100 coats of material when it’s all said and done.

60 Minutes

Bill Whitaker: 100 coats of paint.

Rob Vanderslice: 100 coats of paint.

Rob Vanderslice is a legendary painter from Albuquerque, and a rare “gringo” in New Mexico’s lowrider world.

Rob Vanderslice: Why not utilize the tape, so you end up with a nice little point through the middle?

…famous for using tape and spray paint to lay down layers of different colors, as he demonstrates in weekly YouTube tutorials.

Rob Vanderslice: We’re talkin’ hours and hours. And it just is a beautiful breakup of, like, a darker orange, a medium orange, and then a light orange. It’s kinda a fan of colors.

Vanderslice started painting lowriders in the late 1980s. That’s just about when gangster rap artists popularized the cars in music videos. That contributed to a public impression of lowriders as connected to gangs and drugs.

Bill Whitaker: Back in the day, were most of your clients involved with gangs and drugs?

Rob Vanderslice: Back then, I did a car for just about every gang you could think, you know what I mean?

Vanderslice himself had a years-long addiction to crystal meth while he was making a name for himself painting all those cars.

Bill Whitaker: Congratulations on– on being clean.

Rob Vanderslice: Thank you. Thank you–

Bill Whitaker: How long? How long have you–

Rob Vanderslice: Thirteen years clean now–

Bill Whitaker: And how’d you do it?

Rob Vanderslice: Got in trouble. I’m a three-time convicted felon. And– the last time I just said, “You know what? I’m done.”

His personal rehabilitation parallels the path traveled by New Mexico’s lowriders. counter-culture rebels, turned gangsters, now steadily rolling into the mainstream.

Bill Whitaker: So you have gone from painting cars for gangs to painting cars for the Albuquerque Police Department.

Rob Vanderslice: Right. Right.

Bill Whitaker: That’s a big leap.

Rob Vanderslice: Yeah, that’s a huge leap.

In the lowriders’ leap, Patricia Trujillo remembers a particular pivot.

Patricia Trujillo: In the Plaza in Santa Fe, lowriding had been banned for many years.

60 Minutes

Santa Fe is the capital of New Mexico and its artistic center, so when the city’s mayor not only dropped the ban on cruising but declared a “Lowrider Day” in 2016, Trujillo says cars slow-rolled in by the hundreds.

Patricia Trujillo: There was this real shift in culture in that moment of recognizing– lowriders as an important part of our heritage, an important part of the artistry– of our communities. And I really feel like that marked a new moment in New Mexico.

Joan Medina: So we’re all a family.

Joan and Arthur Medina – everyone calls him “Low Low” – personify the morphing of lowriders’ image in the Espanola Valley. She was in junior high school when they met more than 40 years ago.

Joan Medina: As we were driving into Espanola, I’m like, “Oh, my gosh, look at that car.” And then I was like, “Look at the guy in it.” I told my aunt.

Bill Whitaker: Was his car better than everybody else’s car?

Joan Medina: We don’t like to compete–

Bill Whitaker: Ahh, OK.

Joan Medina: –with people, but (whispers) Yeah!

Bill Whitaker: It stood out more.

Joan Medina: –it stood out more, a lot more. You could see it for miles.

That car is still in a makeshift museum full of lowriders outside their home, with a few in the yard awaiting makeovers. Low Low’s “masterpiece” – covered front, back, and sides with murals depicting the life of Jesus – was being re-painted the day we were there.

Bill Whitaker: Is your– is your car an– a– making a statement?

Joan Medina: Yes.

Arthur Medina: Yes.

Bill Whitaker: W– what’s that statement?

Arthur Medina: It’s our f– it’s our fishing net.

Joan Medina: Wherever we take our cars, people are drawn to his artwork, people are drawn to what we’ve done to the cars and who we are, and people know us from all over.

Bill Whitaker: So it draws people in.

Joan Medina: It draws people.

60 Minutes

But if drawing attention was once the only goal, they’re now using that attention to help kids and serve their community.

Bill Whitaker: Words now, we’re saying family, community, faith. In the past, words associated with lowriders were “gangs,” “drugs,” and “crime.”

Joan Medina: Yes, it’s very true.

Bill Whitaker: What changed?

Joan Medina: I think what changed in a big way, is that we started– being out more in the community, to kind of volunteer.

Arthur Medina: –we’re always here to encourage, we’re always here to help.

Joan Medina: We saw a need for the homeless. And I said, “OK, let’s do a coat drive and a clothing drive.” Man, (clap) we got five huge truckloads of jackets and clothes and shoes.

Bill Whitaker: Is it almost as simple as the original lowriders– have just grown out of their rebellious ways?

Patricia Trujillo: I wouldn’t say they’ve grown out of rebellion. I think that they’ve redefined it, right?

Bill Whitaker: What’s the definition of rebellion now?

Patricia Trujillo: Rebellion now– is healing. To be that beacon of hope, right?

Espanola needs hope. With rates of poverty, crime and drug addiction well above state and national averages, despair is part of the landscape.

Ben Sandoval: A lot of our kids are from broken homes.

Ben Sandoval is director of the YMCA teen center in Espanola.

60 Minutes

Ben Sandoval: There’s drugs. There’s bad influences. What we try to do through the teen center is to provide them a safe place.

In 2023, Sandoval got a grant from the DEA – yes, the Drug Enforcement Administration – for a project to build lowrider bicycles.

Bill Whitaker: How does that help with the at-risk kids?

Ben Sandoval: First of all, it gives ’em an opportunity to say, “Hey, I gotta get to the teen center after school every Wednesday.” They have to feel that they’re valued in their role as the engineer, as the designer, as the planner —

Ben Sandoval: They do it all.

The finished bikes were so creative, so impressive, the prestigious museum of Spanish Colonial Art in Santa Fe mounted a special exhibition to put them on display!

Bill Whitaker: It really is quite beautiful art.

Ben Sandoval: Thank you–

Bill Whitaker: These kids have created.

Ben Sandoval: It’s remarkable. It was just this vibrant buzz of happiness in the room during the opening.

Bill Whitaker: Yeah. The kids hadn’t seen ’em like this before–

Ben Sandoval: No. Never. And I’d sit back with three or four youth, and I say, “Look at that. They’re– they’re taking pictures of YOUR bike. That’s what YOU did.”

Car shows now feature lowrider bicycles, with trophies for the best. Same for kids with radio-controlled cars that tilt and bounce. And the fanciest car shows rival any museum display.

Patricia Trujillo: Now when you see– cruises, it literally can feel like a– moving art exhibit, right, as you’re watching it go by.

Bill Whitaker: A moving art exhibit?

Patricia Trujillo: Yes.

Bill Whitaker: That’s pretty good.

Joan Medina’s artwork is a glittering grand prix. She and Low Low loved showing it off for us, on an afternoon cruise in the hills above Espanola.

Low Low Medina: All cars have a different style when you’re cruisin’ ’em

Bill Whitaker: This one, I have to say, is eye-catching.

Joan Medina: Thank you. That’s what I wanted.

Produced by Rome Hartman. Associate producers, Sara Kuzmarov and Matthew Riley. Broadcast associate, Mariah B. Campbell. Edited by Michael Mongulla.