CBS News

The evidence presented at Michelle Troconis’ murder conspiracy trial

Michelle Troconis was convicted of helping her boyfriend Fotis Dulos murder his estranged wife. Prosecutors say she helped plan the murder, destroy evidence and create an alibi for Fotis Dulos.

Here’s a look at the evidence presented at her trial.

Pool

Testimony began in the trial of Troconis, 49, on Jan. 11, 2024. She was charged with conspiracy to commit murder, along with tampering with physical evidence and hindering prosecution. Over the next six weeks, prosecutors would present evidence they say proves Troconis hated Jennifer Dulos and wanted her gone.

How the story began

Carrie Luft

On May 24, 2019, Jennifer Dulos vanished. The mother and writer was last seen near her New Canaan, Connecticut, home after dropping her five children off at school. She was reported missing around 7 p.m. that evening. Police soon launched a massive search.

Blood in Jennifer Dulos’ garage

Connecticut State Police

When New Canaan Police arrived at Jennifer Dulos’ rented home, they found blood on the floor of the garage. A little over an hour later, detectives found her Suburban SUV — also containing blood evidence — abandoned by nearby Waveny Park.

Fotis and Jennifer Dulos’ contentious divorce

Sotiria Kontouli

Detectives learned that Jennifer Dulos was embroiled in a bitter divorce and custody battle with her husband Fotis Dulos, a luxury home builder. The couple was living separately at the time of Jennifer Dulos’ disappearance. Former Connecticut State Police Sgt. Kenneth Ventresca told “48 Hours” that Fotis Dulos didn’t help with the search and “never seemed concerned about his wife.”

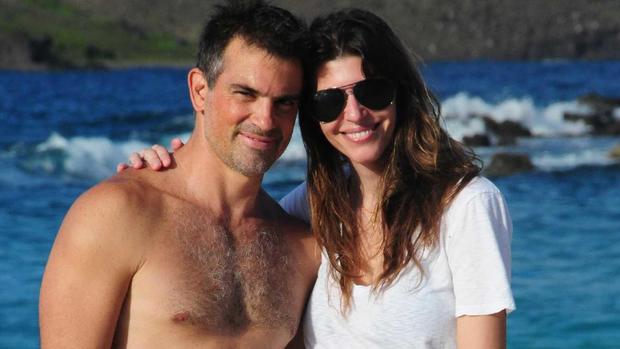

A new love interest for Fotis Dulos

Sotiria Kontouli

Detectives also learned Fotis Dulos had a new woman in his life — live-in girlfriend Michelle Troconis, who he had met at a waterskiing club in Miami.

Fotis Dulos and Michelle Troconis on Albany Avenue

Connecticut State Police

Police soon learn that Fotis Dulos and Troconis drove around Albany Avenue in Hartford, Connecticut, together the evening of the day that Jennifer Dulos disappeared. They spotted Fotis Dulos on surveillance footage throwing away black garbage bags.

Michelle Troconis seen on surveillance footage

Connecticut State Police

At one of the stops, Troconis is seen leaning out of Fotis Dulos’ vehicle. She would later tell police that she had spit out gum and since her hand was sticky, she decided to wipe it on the sidewalk. Police didn’t believe her — especially after they saw what was in those garbage bags.

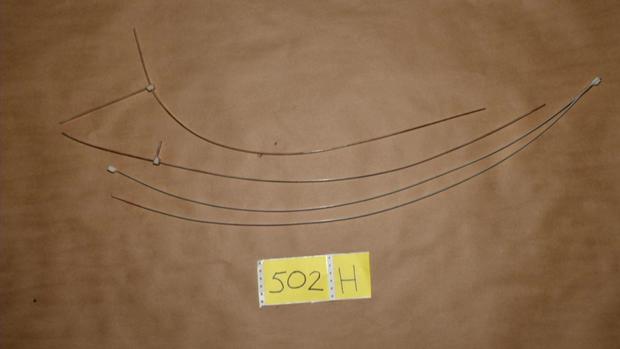

Investigators discover more bloody evidence

Connecticut State Police

Detectives descended on Albany Avenue and began digging through the trash discarded by Fotis Dulos. They found clothing in Jennifer Dulos’ size, ponchos and cut zip ties (pictured). The items were covered in blood matching Jennifer Dulos’ DNA, convincing detectives of what they already suspected: this was a homicide. They believed Fotis Dulos was responsible for her murder, and that Troconis helped plan the murder and dispose of incriminating items.

Michelle Troconis and Fotis Dulos charged

Michelle Troconis

Troconis was many things — a mother, former ESPN reporter in South America, horseback rider — but now she was an alleged conspirator in her boyfriend’s wife’s disappearance. She was charged with conspiracy to commit murder and Fotis Dulos was charged with murder. Fotis Dulos would never stand trial. He died by suicide eight months after Jennifer Dulos disappeared, leaving Troconis to face the consequences alone.

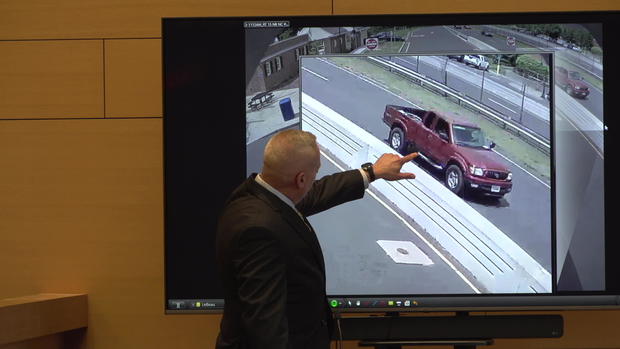

Michelle Troconis’ trial begins

Pool

To prove that Troconis conspired with Fotis Dulos to commit murder, prosecutors first had to prove there was a murder, and then, that it was Fotis Dulos who murdered her. The State took the jury step-by-step through what they believe happened, telling the story through surveillance videos. Their timeline began with this old red Toyota Tacoma truck belonging to one of Fotis Dulos’ employees. Police believe Fotis Dulos took it without permission on May 24, 2019, and drove it to New Canaan.

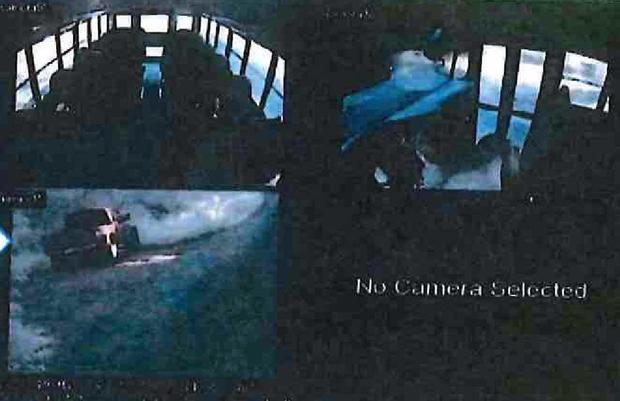

Evidence captured on bus video

Connecticut State Police

Police found this video from a passing school bus of the Tacoma on the side of the road near Waveny Park in New Canaan at 7:57 a.m. It was approximately 100 feet from where Jennifer’ Dulos’ Suburban was later found.

A mysterious cyclist caught on camera

Connecticut State Police

The State showed the jury this surveillance video of a figure in dark clothing. Prosecutors believe Fotis Dulos had brought a bicycle with him in the Tacoma, and that it shows him biking the last three miles to Jennifer Dulos’ house. Prosecutors believe Fotis Dulos was lying in wait and assaulted her in her garage.

An alibi for Fotis Dulos

Authorities believe Fotis Dulos spent the next couple of hours cleaning up, but that he left behind evidence—his DNA on a doorknob and a mixture of his and Jennifer Dulos’ DNA on a faucet in the kitchen. Meanwhile, prosecutors say, Troconis was at the home she shared with Fotis Dulos, helping him create an alibi. Fotis Dulos had left his phone at home and prearranged a call with a friend. Prosecutors believe Troconis picked up the call to make it appear that Fotis Dulos was home, an allegation she denies.

Evidence in the Tacoma

Pool

Police then think Fotis Dulos drove Jennifer Dulos’ SUV to Waveny Park and transferred her body or bloody evidence into the Tacoma. They later tested a fabric sample from a seat in the Tacoma and it came back positive for Jennifer Dulos’ blood.

Michelle Troconis talks to investigators

Connecticut State Police

The next part of the police theory comes from Michelle Troconis. During a series of three interviews, she told investigators that she and Fotis Dulos had lunch together on the afternoon of May 24. Afterwards, she said that she and Fotis Dulos went to one of his properties to clean it for a showing that was scheduled for the next day. Prosecutors believe they were bagging up evidence and cleaning the Tacoma, before heading to Albany Avenue to throw away those incriminating items.

Smoke rising from Fotis Dulos and Michelle Troconis’ home

Pool

Prosecutors say that same day, Troconis was caught burning evidence in the home she shared with Fotis. They point to this surveillance footage from a home across the street showing smoke rising from the chimney — on what was a mild spring day in May.

Fotis Dulos at the car wash

Connecticut State Police

Prosecutors showed the jury video of Fotis Dulos once again driving the Tacoma. Five days after Jennifer Dulos went missing, he brought the truck to a local car wash and detail shop. That’s him paying for the cleaning. Troconis met him there.

Jennifer Dulos’ clothing shown in court

Pool

One of the most emotional moments of the trial was when Prosecutor Michelle Manning held up some of the evidence police recovered from the bags Fotis Dulos had dumped on Albany Avenue, including a bloody shirt that belonged to Jennifer Dulos. Jennifer Dulos’ close friend Carrie Luft was in the courtroom. She told “48 Hours,” “being in … the same space and time as Jennifer’s clothes just really drove home that she’s not here.”

Jon Schoenhorn delivers closing arguments

Pool

After six weeks of testimony, it was time for closing arguments. Troconis’ attorney Jon Schoenhorn told the jury that Troconis was not involved in any plan to murder Jennifer Dulos and that the State’s case was based on “speculation.” He said that Fotis Dulos had simply invited her to go on a Starbucks run the day he was dumping evidence, and Troconis didn’t know what was inside the bags. He also said that Troconis would often light the fireplace and was burning nothing more than firewood that day.

The prosecution’s final statements

Pool

During Prosecutor Sean McGuinness’ closing arguments, he focused on one simple word: “coincidence.” “Is it just a coincidence that the defendant answered Dulos’ phone … when he was murdering his wife in New Canaan?” he asked the jury. “Is it just a coincidence that the defendant travels with Dulos to Hartford as he disposes of the evidence on the same day?”

Troconis family reacts to guilty verdict

CBS News

After deliberating a little more than two days, the jury reached a verdict: guilty. Outside, Troconis’ family, who had sat behind her throughout the trial, made an emotional statement to the media. “We don’t know what happened to Jennifer,” said Troconis’ sister, Claudia Troconis-Marmol, through her tears. “And choosing and putting my sister as the guilty person is not the right thing to do because she’s innocent.”

Jennifer Dulos: Five years gone

Carrie Luft

In May 2024, it will be five years since Jennifer Dulos disappeared. Police have been unable to find her body. “And that’s what’s the most painful… We don’t know where she is,” Luft told “48 Hours.” “Jennifer’s still here in so many ways. But I think it would bring some peace to be able to let her rest in peace.”

CBS News

How Kenya became the “Silicon Savannah”

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

Kenyan workers with AI jobs thought they had tickets to the future until the grim reality set in

Being overworked, underpaid, and ill-treated is not what Kenyan workers had in mind when they were lured by U.S. companies with jobs in AI.

Kenyan civil rights activist Nerima Wako-Ojiwa said the workers’ desperation, in a country with high unemployment, led to a culture of exploitation with unfair wages and no job security.

“It’s terrible to see just how many American companies are just doing wrong here,” Wako-Ojiwa said. “And it’s something that they wouldn’t do at home, so why do it here?”

Why tech giants come to Kenya

The familiar narrative is that artificial intelligence will take away human jobs, but right now it’s also creating jobs. There’s a growing global workforce of millions toiling to make AI run smoothly. It’s gruntwork that needs to be done accurately and fast. To do it cheaply, the work is often farmed out to developing countries like Kenya.

Nairobi, Kenya, is one of the main hubs for this kind of work. It’s a country desperate for work. The unemployment rate is as high as 67% among young people.

“The workforce is so large and desperate that they could pay whatever and have whatever working conditions, and they will have someone who will pick up that job,” Wako-Ojiwa said.

60 Minutes

Every year, a million young people enter the job market, so the government has been courting tech giants like Microsoft, Google, Apple and Intel. Officials have promoted Kenya as a “Silicon Savannah” — tech savvy and digitally connected.

Kenyan President William Ruto has offered financial incentives on top of already lax labor laws to attract the tech companies.

What “humans in the loop” do with AI

Naftali Wambalo, a father of two with a college degree in mathematics, was elated to find work in Nairobi in the emerging field of artificial intelligence. He is what’s known as a “human in the loop”: someone sorting, labeling and sifting through reams of data to train and improve AI for companies like Meta, OpenAI, Microsoft and Google.

Wambalo and other digital workers spent eight hours a day in front of a screen studying photos and videos, drawing boxes around objects and labeling them, teaching AI algorithms to recognize them.

Human labelers tag cars and pedestrians to teach autonomous vehicles not to hit them. Humans circle abnormalities in CTs, MRIs and X-rays to teach AI to recognize diseases. Even as AI gets smarter, humans in the loop will always be needed because there will always be new devices and inventions that’ll need labeling.

Humans in the loop are found not only in Kenya, but also in India, the Philippines and Venezuela. They’re often countries with low wages but large populations — well educated, but unemployed.

Unfair labor practices

What seemed like a ticket to the future was quickly revealed to be anything but for some humans in the loop, who say they’ve been exploited. The jobs offer no stability – some contracts only offer employment for a few days, some weekly and others monthly, Wako-Ojiwa said. She calls the workspaces AI sweatshops with computers instead of sewing machines.

The workers aren’t typically hired directly by the big tech companies – instead, they are employed by mostly American outsourcing companies.

The pay for humans in the loop is $1.50-2 an hour.

“And that is gross, before tax,” Wambalo said.

Wambalo, Nathan Nkunzimana and Fasica Berhane Gebrekidan were employed by SAMA, an American outsourcing company that hired for Meta and OpenAI. SAMA, based in the California Bay Area, employed over 3,000 workers in Kenya. Documents reviewed by 60 Minutes show OpenAI agreed to pay SAMA $12.50 an hour per worker, much more than the $2 the workers actually got, though SAMA says what it paid is a fair wage for the region.

Wambalo disagrees.

“If the big tech companies are going to keep doing this business, they have to do it the right way,” he said. “It’s not because you realize Kenya’s a third-world country, you say, ‘This job I would normally pay $30 in U.S., but because you are Kenya, $2 is enough for you.'”

60 Minutes

Nkunzimana said he took the job because he has a family to feed.

Berhane Gebrekidan lived paycheck to paycheck, unable to save anything. She said she saw people who were fired for complaining.

“We were walking on eggshells,” she said.

They say SAMA pushed workers to complete assignments faster than the companies required, an allegation SAMA denies. If a six-month contract was completed in three months, they could be out of work without any pay for those extra months. They did say Sama would reward them for fast work.

“They used to say ‘thank you.’ They give you a bottle of soda and KFC chicken. Two pieces. And that is it,” Wambalo said.

Ephantus Kanyugi, Joan Kinyua, Joy Minayo, Michael Geoffrey Asia and Duncan Koech all worked for Remotaks, a click-work platform operated by Scale AI — another American AI training company facing criticism in Kenya. Workers signed up online and selected remote work, getting paid per task. They said they sometimes went unpaid.

“When it gets to the day before payday, they close the account and say that you violated a policy,” Kanyugi said.

Employees say they have no recourse or even a way to complain.

The company told 60 Minutes that any work done “in line with our community guidelines was paid out.” In March, as workers started complaining publicly, Remotasks abruptly shut down in Kenya, locking all workers out of their accounts.

The mental toll of AI training

Workers say some of the projects for Meta and OpenAI also caused them mental harm. Wambalo was assigned to train AI to recognize and weed out pornography, hate speech and excessive violence from social media. He had to sift through the worst of the worst content online for hours on end.

“I looked at people being slaughtered,” Wambalo said. “People engaging in sexual activity with animals. People abusing children physically, sexually. People committing suicide.”

Berhane Gebrekidan thought she’d been hired for a translation job, but she said what she ended up doing was reviewing content featuring dismembered bodies and drone attack victims.

60 Minutes

“I find it hard now to even have conversations with people,” she said. “It’s just that I find it easier to cry than to speak.”

Wambalo said the material he had to review online has hurt his marriage.

“After countlessly seeing those sexual activities, pornography on the job, that I was doing, I hate sex,” he said.

SAMA says mental health counseling was provided by “fully-licensed professionals.” Workers say it was woefully inadequate.

“We want psychiatrists,” Wambalo said. “We want psychologists, qualified, who know exactly what we are going through and how they can help us to cope.”

Workers fight back

Wambalo and Berhane Gebrekidan are among around 200 digital workers suing SAMA and Meta over “unreasonable working conditions” that caused them psychological problems.

“It was proven by a psychiatrist that we are thoroughly sick,” Nathan Nkunzimana said “We have gone through a psychiatric evaluation just a few months ago and it was proven that we are all sick, thoroughly sick.”

Wambalo said it’s the responsibility of the big tech companies to know how the jobs are impacting workers.

“They are the ones providing the work,” he said.

Berhane Gebrekidan feels the companies know the people they employ are struggling, but they don’t care.

“…Just because we’re Black, or just because we’re just vulnerable for now, that doesn’t give them the right to just exploit us like this,” she said.

Kenya does have labor laws, but they are outdated and don’t touch on digital labor, Wako-Ojiwa, the civil rights activist, said.

“I do think that our labor laws need to recognize it, but not just in Kenya alone,” Wako-Ojiwa said. “Because what happens is when we start to push back, in terms of protections of workers, a lot of these companies…they shut down and they move to a neighboring country.”

SAMA has terminated the harmful content projects Wambalo and Berhane Gebrekidan were working on. The company would not agree to an on-camera interview and neither would Scale AI, which operated the Remotasks website in Kenya.

Meta and OpenAi told 60 Minutes they’re committed to safe working conditions, including fair wages and access to mental health counseling.

CBS News

Labelers training AI say they’re overworked, underpaid and exploited by big American tech companies

The familiar narrative is that artificial intelligence will take away human jobs: machine-learning will let cars, computers and chatbots teach themselves – making us humans obsolete.

Well, that’s not very likely, and we’re gonna tell you why. There’s a growing global army of millions toiling to make AI run smoothly. They’re called “humans in the loop:” people sorting, labeling, and sifting reams of data to train and improve AI for companies like Meta, OpenAI, Microsoft and Google. It’s gruntwork that needs to be done accurately, fast, and – to do it cheaply – it’s often farmed out to places like Africa –

Naftali Wambalo: The robots or the machines, you are teaching them how to think like human, to do things like human.

We met Naftali Wambalo in Nairobi, Kenya, one of the main hubs for this kind of work. It’s a country desperate for jobs… because of an unemployment rate as high as 67% among young people. So Naftali, father of two, college educated with a degree in mathematics, was elated to finally find work in an emerging field: artificial intelligence.

Lesley Stahl: You were labeling.

Naftali Wambalo: I did labeling for videos and images.

Naftali and digital workers like him, spent eight hours a day in front of a screen studying photos and videos, drawing boxes around objects and labeling them, teaching the AI algorithms to recognize them.

Naftali Wambalo: You’d label, let’s say, furniture in a house. And you say “This is a TV. This is a microwave.” So you are teaching the AI to identify these items. And then there was one for faces of people. The color of the face. “If it looks like this, this is white. If it looks like this, it’s Black. This is Asian.” You’re teaching the AI to identify them automatically.

60 Minutes

Humans tag cars and pedestrians to teach autonomous vehicles not to hit them. Humans circle abnormalities to teach AI to recognize diseases. Even as AI is getting smarter, humans in the loop will always be needed because there will always be new devices and inventions that’ll need labeling.

Lesley Stahl: You find these humans in the loop not only here in Kenya but in other countries thousands of miles from Silicon Valley. In India, the Philippines, Venezuela – often countries with large low wage populations – well educated but unemployed.

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: Honestly, it’s like modern-day slavery. Because it’s cheap labor–

Lesley Stahl: Whoa. What do you –

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: It’s cheap labor.

Like modern day slavery, says Nerima Wako-Ojiwa, a Kenyan civil rights activist, because big American tech companies come here and advertise the jobs as a ticket to the future. But really, she says, it’s exploitation.

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: What we’re seeing is an inequality.

Lesley Stahl: It sounds so good. An AI job! Is there any job security?

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: The contracts that we see are very short-term. And I’ve seen people who have contracts that are monthly, some of them weekly, some of them days. Which is ridiculous.

She calls the workspaces AIi sweatshops with computers instead of sewing machines.

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: I think that we’re so concerned with “creating opportunities,” but we’re not asking, “Are they good opportunities?”

Because every year a million young people enter the job market, the government has been courting tech giants like Microsoft, Google, Apple, and Intel to come here, promoting Kenya’s reputation as the Silicon Savannah: tech savvy and digitally connected.

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: The president has been really pushing for opportunities in AI –

Lesley Stahl: President?

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: Ruto?

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: President Ruto. Yes. The president does have to create at least one million jobs a year the minimum. So it’s a very tight position to be in.

60 Minutes

To lure the tech giants, Ruto has been offering financial incentives on top of already lax labor laws. but the workers aren’t hired directly by the big companies. They engage outsourcing firms – also mostly American – to hire for them.

Lesley Stahl: There’s a go-between.

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: They hire? They pay.

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: Uh-huh (affirm). I mean, they hire thousands of people.

Lesley Stahl: And they are protecting the Facebooks from having their names associated with this?

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: Yes yes yes.

Lesley Stahl: We’re talking about the richest companies on Earth.

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: Yes. But then they are paying people peanuts.

Lesley Stahl: AI jobs don’t pay much?

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: They don’t pay well. They do not pay Africans well enough. And the workforce is so large and desperate that they could pay whatever, and have whatever working conditions, and they will have someone who will pick up that job.

Lesley Stahl: So what’s the average pay for these jobs?

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: It’s about a $1.50, $2 an hour.

Naftali Wambalo: $2 per hour, and that is gross before tax.

Naftali, Nathan, and Fasica were hired by an American outsourcing company called SAMA – that employs over 3,000 workers here and hired for Meta and OpenAI. In documents we obtained, OpenAI agreed to pay SAMA $12.50 an hour per worker, much more than the $2 the workers actually got – though, SAMA says, that’s a fair wage for the region –

60 Minutes

Naftali Wambalo: If the big tech companies are going to keep doing this– this business, they have to do it the right way. So it’s not because you realize Kenya’s a third-world country, you say, “This job I would normally pay $30 in U.S., but because you are Kenya $2 is enough for you.” That idea has to end.

Lesley Stahl: OK. $2 an hour in Kenya. Is that low, medium? Is it an OK salary?

Fasica: So for me, I was living paycheck to paycheck. And I have saved nothing because it’s not enough.

Lesley Stahl: Is it an insult?

Nathan: It is, of course. It is.

Fasica: It is.

Lesley Stahl: Why did you take the job?

Nathan: I have a family to feed. And instead of staying home, let me just at least have something to do.

And not only did the jobs not pay well – they were draining. They say deadlines were unrealistic, punitive – with often just seconds to complete complicated labeling tasks.

Lesley Stahl: Did you see people who were fired just ’cause they complained?

Fasica: Yes, we were walking on eggshells.

They were all hired per project and say SAMA kept pushing them to complete the work faster than the projects required, an allegation SAMA denies.

Lesley Stahl: Let’s say the contract for a certain job was six months, OK? What if you finished in three months? Does the worker get paid for those extra three months?

Male voice: No –

Fasica: KFC.

Lesley Stahl: What?

Fasica: We used to get KFC and Coca Cola.

Naftali Wambalo: They used to say thank you. They give you a bottle of soda and KFC chicken. Two pieces. And that is it.

Worse yet, workers told us that some of the projects for Meta and OpenAI were grim and caused them harm. Naftali was assigned to train AI to recognize and weed out pornography, hate speech and excessive violence, which meant sifting through the worst of the worst content online for hours on end.

Naftali Wambalo: I looked at people being slaughtered, people engaging in sexual activity with animals. People abusing children physically, sexually. People committing suicide.

Lesley Stahl: All day long?

Naftali Wambalo: Basically- yes, all day long. Eight hours a day, 40 hours a week.

The workers told us they were tricked into this work by ads like this that described these jobs as “call center agents” to “assist our clients’ community and help resolve inquiries empathetically.”

Fasica: I was told I was going to do a translation job.

Lesley Stahl: Exactly what was the job you were doing?

Fasica: I was basically reviewing content which are very graphic, very disturbing contents. I was watching dismembered bodies or drone attack victims. You name it. You know, whenever I talk about this, I still have flashbacks.

Lesley Stahl: Are any of you a different person than they were before you had this job?

Fasica: Yeah. I find it hard now to even have conversations with people. It’s just that I find it easier to cry than to speak.

Nathan: You continue isolating you– yourself from people. You don’t want to socialize with others. It’s you and it’s you alone.

Lesley Stahl: Are you a different person?

Naftali Wambalo: Yeah. I’m a different person. I used to enjoy my marriage, especially when it comes to bedroom fireworks. But after the job I hate sex.

Lesley Stahl: You hated sex?

Naftali Wambalo: After countlessly seeing those sexual activities pornography on the job that I was doing, I hate sex.

SAMA says mental health counseling was provided by quote “fully licensed professionals.” But the workers say it was woefully inadequate.

Naftali Wambalo: We want psychiatrists. We want psychologists, qualified, who know exactly what we are going through and how they can help us to cope.

Lesley Stahl: Trauma experts.

Naftali Wambalo: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: Do you think the big company, Facebook, ChatGPT, do you think they know how this is affecting the workers?

Naftali Wambalo: It’s their job to know. It’s their f***ing job to know, actually– because they are the ones providing the work.

60 Minutes

These three and nearly 200 other digital workers are suing SAMA and Meta over “unreasonable working conditions” that caused psychiatric problems

Nathan: It was proven by a psychiatrist that we are thoroughly sick. We have gone through a psychiatric evaluation just a few months ago and it was proven that we are all sick, thoroughly sick.

Fasica: They know that we’re damaged but they don’t care. We’re humans just because we’re black, or just because we’re just vulnerable for now, that doesn’t give them the right to just exploit us like this.

SAMA – which has terminated those projects – would not agree to an on-camera interview. Meta and OpenAI told us they’re committed to safe working conditions including fair wages and access to mental health counseling. Another American AI training company facing criticism in Kenya is Scale AI, which operates a website called Remotasks.

Lesley Stahl: Did you all work for Remotasks?

Group: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: Or work with them?

Ephantus, Joan, Joy, Michael, and Duncan signed up online, creating an account, and clicked for work remotely, getting paid per task. Problem is: sometimes the company just didn’t pay them.

Ephantus: When it gets to the day before payday, they close the account and say that “You violated a policy.”

Lesley Stahl: They say, “You violated their policy.”

Voice: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: And they don’t pay you for the work you’ve done—

Ephantus: They don’t.

Lesley Stahl: Would you say that that’s almost common, that you do work and you’re not paid for it?

Joan: Yeah.

Lesley Stahl: And you have no recourse, you have no way to even complain?

Joan: There’s no way.

The company says any work that was done “in line with our community guidelines was paid out.” In March, as workers started complaining publicly, Remotasks abruptly shut down in Kenya altogether.

Lesley Stahl: There are no labor laws here?

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: Our labor law is about 20 years old, it doesn’t touch on digital labor. I do think that our labor laws need to recognize it– but not just in Kenya alone. Because what happens is when we start to push back, in terms of protections of workers, a lot of these companies, they shut down and they move to a neighboring country.

Lesley Stahl: It’s easy to see how you’re trapped. Kenya is trapped: They need jobs so desperately that there’s a fear that if you complain, if your government complained, then these companies don’t have to come here.

Nerima Wako-Ojiwa: Yeah. And that’s what they throw at us all the time. And it’s terrible to see just how many American companies are just-just doing wrong here– just doing wrong here. And it’s something that they wouldn’t do at home, so why do it here?

Produced by Shachar Bar-On and Jinsol Jung. Broadcast associate, Aria Een. Edited by April Wilson.