CBS News

Inside a huge U.S. military exercise in Africa to counter terrorism and Russia and China’s growing influence

Tamale, Ghana — On a dusty airport tarmac in the northern Ghanaian city of Tamale, military special operatives from across Africa move stealthily. Shots ring out as they converge on the airport and apprehend armed militants holding it hostage.

It’s not a real attack, but just one of the exercises of “Flintlock,” the U.S. military’s premier counterterrorism training event in Africa, which is now in its 20th year.

Special ops teams from the U.S. military’s Africa Command, along with NATO allies, are conducting drills alongside soldiers from countries including Ghana, Ivory Coast, Chad, Mauritania, Nigeria, Libya and Morocco.

In the exercise CBS News witnessed, the elite forces were rescuing hostages from a simulated attack on an airport. It’s a very real scenario in the vast North African region known as the Sahel, which is considered the epicenter of the global fight against ISIS and al Qaeda franchises.

Getty/iStockphoto

The Sahel stretches from Mauritania in the west through Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, all the way to Eritrea and Djibouti on Africa’s east coast, and it is home to the fastest growing and most deadly terror groups in the world.

Ghana is one of the few countries in the region that has managed to dodge the rapid rise of violent extremism — blocking any potential incursions before they reach its borders.

Gen. Frank Tei of the Ghana Armed Forces told CBS News that was vital, because “once you allow terrorist activities in a particular country to fester and blossom, then that place can become a base from which a lot of other terrorist activities can spread across the globe.”

That’s exactly what the U.S. fears and is trying to help prevent.

The deputy AFRICOM commander, Lt. Gen. John Brennan, told CBS News that the Flintlock exercise is not only about training African forces to defend themselves and combat terrorism, however.

“We offer things that are meaningful in the long term — sharing democratic values, instilling rule of law,” he said.

But that hasn’t worked out so well over the past decade. There have been 11 coups in the Sahel alone over that period, and at least 14 leaders of those armed government overthrows were trained at Flintlock.

Brennan told CBS News the military tracks these leaders, and while there are strict rules of engagement with any country in which the government has been toppled by a military junta, “the hope is that you keep contact with the military partners and then you pull them away from military-led governments, which never last.”

So how can the U.S. ensure the skills taught at events like Flintlock are not later weaponized and used to subvert democracy?

Brennan is quick to point out that executing a coup is a political maneuver, not a military one.

“We teach them how to protect their forces in combat and then conduct successful counterterrorism operations. That has nothing to do with overthrowing a government. It’s just some of the people we’ve trained are military and they’re involved in some of the coups,” he said. “But history has shown … democracy ends up prevailing in a lot of countries.”

Flintlock has expanded to include maritime training — including rappelling onto a moving warship hijacked by armed militants. American forces, along with Italian and Dutch soldiers, put African troops through their paces on a frigate off the Ghanaian coast.

CBS News

This aspect of the exercises is increasingly important, given that the Sahel region runs all the way to the Red Sea, where the Iran-backed Houthi rebels have been launching attacks targeting international shipping and U.S. naval vessels.

The annual Flintlock training operation — hosted this year by Ghana — could not have come at a more crucial time for the U.S. military, as American influence is arguably in deep decline across the vast African continent.

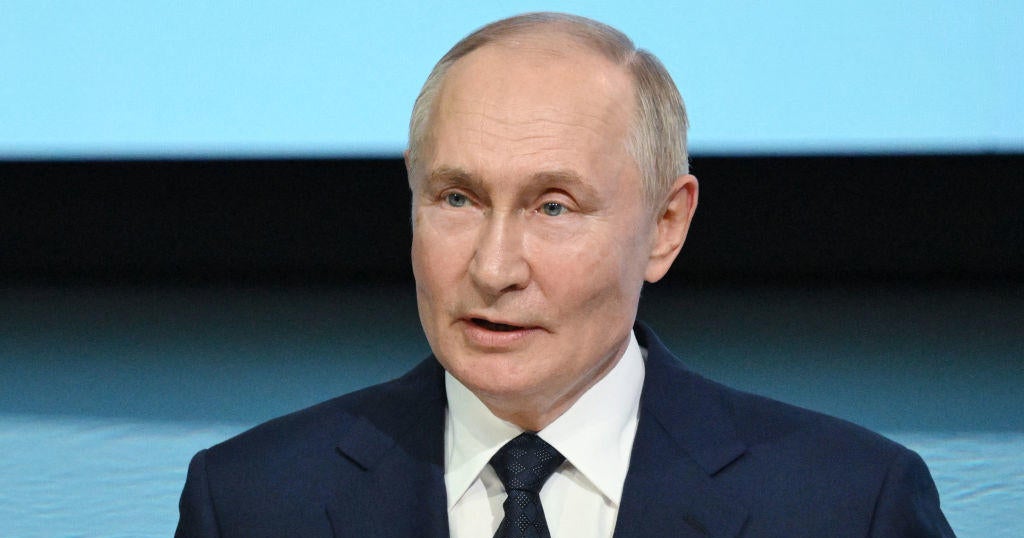

The U.S. is up against stiff competition. China offers Africa’s national leaders trade agreements and Russia offers military aid, and all with very few strings attached. Washington, meanwhile, has been booted off one key front line in the fight against terrorism, after the more than 1,000 troops AFRICOM had stationed in Niger were ordered to leave the country by September following a coup there last year.

Djibo Issifou/picture alliance via Getty Images

The U.S. has two military bases in Niger, including a drone command center in the city of Agadez that cost more than $110 million to set up.

Russia quickly stepped in to exploit the power vacuum created by the coup. Mercenaries from the former Wagner Group, now called Africa Corps and run by the Russian government, arrived in Niger in April.

In a scenario that was not long ago unimaginable, the Russian and American forces now occupy opposite sides of the same sprawling air base.

That has sent alarm bells ringing in Washington, and U.S. Ambassador to Ghana Virginia Palmer stressed to CBS News that African nations should understand that Russia’s offer of security forces does not come completely without strings attached.

“It’s important that our African partners understand that what the Russians are offering is, maybe regime protection — it’s certainly not national security,” Palmer said.

She said African countries do pay for the services offered by Moscow, and at a cost that “is extraordinarily high.”

Niger is rich in uranium, which can be used to make nuclear weapons. What Russia provides is military muscle in exchange for mineral wealth, but unlike the U.S., the deal comes with no potentially tricky human rights questions being asked.

“But time will tell that that decision is probably not a good one,” the ambassador said. “So, you don’t feed your kids ice cream for dinner every night because they want it, right? You feed them vegetables, you feed them spinach, things that are good for them … instant gratification is probably not a recipe for success.”

U.S. law restricts the provision of military aid to armed forces believed to be guilty of human rights abuses, but many leaders on the continent accuse Washington of having double standards — saying the U.S. withholds aid from some African nations while giving Israel billions of dollars despite global condemnation of its actions in the war in Gaza.

It’s a charge that Brennan disputes.

“I don’t think there’s a double standard,” he told CBS News. “I can tell you our values and the people we do partner with — even after coups — we’re still able to influence them.”

African countries argue that it isn’t just training they need, but resources and modern military equipment if they hope to counter rising extremism.

Brennan stressed that the U.S. carries with it the weight of the entire NATO alliance, unlike its competitors, but he conceded that Washington must “be able to resource our partners appropriately, and really expand the relationship with them … to help make Africa prosperous, free and a partner of choice.”

With Flintlock, the U.S. promises long-term investment in the African continent. But that long-view security strategy is competing for African partnerships amid a fast-growing terror threat, on a battlefield crowded with malign actors.

CBS News

A lowrider artist’s journey “out of the darkness”

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

How Kenya became the “Silicon Savannah”

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

Kenyan workers with AI jobs thought they had tickets to the future until the grim reality set in

Being overworked, underpaid, and ill-treated is not what Kenyan workers had in mind when they were lured by U.S. companies with jobs in AI.

Kenyan civil rights activist Nerima Wako-Ojiwa said the workers’ desperation, in a country with high unemployment, led to a culture of exploitation with unfair wages and no job security.

“It’s terrible to see just how many American companies are just doing wrong here,” Wako-Ojiwa said. “And it’s something that they wouldn’t do at home, so why do it here?”

Why tech giants come to Kenya

The familiar narrative is that artificial intelligence will take away human jobs, but right now it’s also creating jobs. There’s a growing global workforce of millions toiling to make AI run smoothly. It’s gruntwork that needs to be done accurately and fast. To do it cheaply, the work is often farmed out to developing countries like Kenya.

Nairobi, Kenya, is one of the main hubs for this kind of work. It’s a country desperate for work. The unemployment rate is as high as 67% among young people.

“The workforce is so large and desperate that they could pay whatever and have whatever working conditions, and they will have someone who will pick up that job,” Wako-Ojiwa said.

60 Minutes

Every year, a million young people enter the job market, so the government has been courting tech giants like Microsoft, Google, Apple and Intel. Officials have promoted Kenya as a “Silicon Savannah” — tech savvy and digitally connected.

Kenyan President William Ruto has offered financial incentives on top of already lax labor laws to attract the tech companies.

What “humans in the loop” do with AI

Naftali Wambalo, a father of two with a college degree in mathematics, was elated to find work in Nairobi in the emerging field of artificial intelligence. He is what’s known as a “human in the loop”: someone sorting, labeling and sifting through reams of data to train and improve AI for companies like Meta, OpenAI, Microsoft and Google.

Wambalo and other digital workers spent eight hours a day in front of a screen studying photos and videos, drawing boxes around objects and labeling them, teaching AI algorithms to recognize them.

Human labelers tag cars and pedestrians to teach autonomous vehicles not to hit them. Humans circle abnormalities in CTs, MRIs and X-rays to teach AI to recognize diseases. Even as AI gets smarter, humans in the loop will always be needed because there will always be new devices and inventions that’ll need labeling.

Humans in the loop are found not only in Kenya, but also in India, the Philippines and Venezuela. They’re often countries with low wages but large populations — well educated, but unemployed.

Unfair labor practices

What seemed like a ticket to the future was quickly revealed to be anything but for some humans in the loop, who say they’ve been exploited. The jobs offer no stability – some contracts only offer employment for a few days, some weekly and others monthly, Wako-Ojiwa said. She calls the workspaces AI sweatshops with computers instead of sewing machines.

The workers aren’t typically hired directly by the big tech companies – instead, they are employed by mostly American outsourcing companies.

The pay for humans in the loop is $1.50-2 an hour.

“And that is gross, before tax,” Wambalo said.

Wambalo, Nathan Nkunzimana and Fasica Berhane Gebrekidan were employed by SAMA, an American outsourcing company that hired for Meta and OpenAI. SAMA, based in the California Bay Area, employed over 3,000 workers in Kenya. Documents reviewed by 60 Minutes show OpenAI agreed to pay SAMA $12.50 an hour per worker, much more than the $2 the workers actually got, though SAMA says what it paid is a fair wage for the region.

Wambalo disagrees.

“If the big tech companies are going to keep doing this business, they have to do it the right way,” he said. “It’s not because you realize Kenya’s a third-world country, you say, ‘This job I would normally pay $30 in U.S., but because you are Kenya, $2 is enough for you.'”

60 Minutes

Nkunzimana said he took the job because he has a family to feed.

Berhane Gebrekidan lived paycheck to paycheck, unable to save anything. She said she saw people who were fired for complaining.

“We were walking on eggshells,” she said.

They say SAMA pushed workers to complete assignments faster than the companies required, an allegation SAMA denies. If a six-month contract was completed in three months, they could be out of work without any pay for those extra months. They did say Sama would reward them for fast work.

“They used to say ‘thank you.’ They give you a bottle of soda and KFC chicken. Two pieces. And that is it,” Wambalo said.

Ephantus Kanyugi, Joan Kinyua, Joy Minayo, Michael Geoffrey Asia and Duncan Koech all worked for Remotaks, a click-work platform operated by Scale AI — another American AI training company facing criticism in Kenya. Workers signed up online and selected remote work, getting paid per task. They said they sometimes went unpaid.

“When it gets to the day before payday, they close the account and say that you violated a policy,” Kanyugi said.

Employees say they have no recourse or even a way to complain.

The company told 60 Minutes that any work done “in line with our community guidelines was paid out.” In March, as workers started complaining publicly, Remotasks abruptly shut down in Kenya, locking all workers out of their accounts.

The mental toll of AI training

Workers say some of the projects for Meta and OpenAI also caused them mental harm. Wambalo was assigned to train AI to recognize and weed out pornography, hate speech and excessive violence from social media. He had to sift through the worst of the worst content online for hours on end.

“I looked at people being slaughtered,” Wambalo said. “People engaging in sexual activity with animals. People abusing children physically, sexually. People committing suicide.”

Berhane Gebrekidan thought she’d been hired for a translation job, but she said what she ended up doing was reviewing content featuring dismembered bodies and drone attack victims.

60 Minutes

“I find it hard now to even have conversations with people,” she said. “It’s just that I find it easier to cry than to speak.”

Wambalo said the material he had to review online has hurt his marriage.

“After countlessly seeing those sexual activities, pornography on the job, that I was doing, I hate sex,” he said.

SAMA says mental health counseling was provided by “fully-licensed professionals.” Workers say it was woefully inadequate.

“We want psychiatrists,” Wambalo said. “We want psychologists, qualified, who know exactly what we are going through and how they can help us to cope.”

Workers fight back

Wambalo and Berhane Gebrekidan are among around 200 digital workers suing SAMA and Meta over “unreasonable working conditions” that caused them psychological problems.

“It was proven by a psychiatrist that we are thoroughly sick,” Nathan Nkunzimana said “We have gone through a psychiatric evaluation just a few months ago and it was proven that we are all sick, thoroughly sick.”

Wambalo said it’s the responsibility of the big tech companies to know how the jobs are impacting workers.

“They are the ones providing the work,” he said.

Berhane Gebrekidan feels the companies know the people they employ are struggling, but they don’t care.

“…Just because we’re Black, or just because we’re just vulnerable for now, that doesn’t give them the right to just exploit us like this,” she said.

Kenya does have labor laws, but they are outdated and don’t touch on digital labor, Wako-Ojiwa, the civil rights activist, said.

“I do think that our labor laws need to recognize it, but not just in Kenya alone,” Wako-Ojiwa said. “Because what happens is when we start to push back, in terms of protections of workers, a lot of these companies…they shut down and they move to a neighboring country.”

SAMA has terminated the harmful content projects Wambalo and Berhane Gebrekidan were working on. The company would not agree to an on-camera interview and neither would Scale AI, which operated the Remotasks website in Kenya.

Meta and OpenAi told 60 Minutes they’re committed to safe working conditions, including fair wages and access to mental health counseling.