CBS News

Book excerpt: “This Strange Eventful History” by Claire Messud

W.W. Norton

We may receive an affiliate commission from anything you buy from this article.

Claire Messud, the bestselling author of “The Emperor’s Children,” returns with “This Strange Eventful History” (W.W. Norton), a multi-generational story of family secrets spanning World War II to the 21st century.

Read an excerpt below.

“This Strange Eventful History” by Claire Messud

Prefer to listen? Audible has a 30-day free trial available right now.

Prologue

I’m a writer; I tell stories. Of course, really, I want to save lives. Or simply: I want to save life.

Seven years, the clairvoyant said, that summer afternoon already long ago. Seven years in the Valley of the Shadow. The sunlight through the window behind her head transformed her rusty curls into a golden nimbus. We sat opposite each other over a card table in the front room of her chintzy saltbox, a mile from the waterfront in a seaside New England holiday town. Like most of her clients, I was just passing through. Though I told her I was a writer, she insisted that I was a healer; once she said it, I willed it to be true. Or: I realized I had always willed it to be true, though we’re told that poetry makes nothing happen. My desire, as old as humanity, to make words signify.

Seven years’ journey in the shadow of Death: at the time of her prophecy, I was almost halfway through, if one counted from the family trip to my late grandparents’ home in Toulon, France, to celebrate my father’s seventy-fifth—a work, as was said, of colossal administration, a gathering that was also an unraveling: my father in physical collapse, my mother, gaunt, in mental disarray, my aunt dancing in ever tighter circles around her bottle of whiskey, our children, still small, antic in the Mediterranean sun. But the count could have started sooner—from the time my mother could no longer manage to prepare a full meal; or the time, well before, when she could no longer keep track of the kids’ birthdays; or, before that still, when she couldn’t, for even an hour, manage the kids themselves. … But if I start at the end and count backward—the end being the last death, my aunt’s death, fast on the heels of my mother’s, neither death long after my father’s—then the Cape clairvoyant held my trembling hand in hers truly at the midpoint.

I’m a writer; I tell stories. I want to tell the stories of their lives. It doesn’t really matter where I start. We’re always in the middle; wherever we stand, we see only partially. I know also that everything is connected, the constellations of our lives moving together in harmony and disharmony. The past swirls along with and inside the present, and all time exists at once, around us. The ebb and flow, the harmonies and dissonance—the music happens, whether or not we describe it. A story is not a line; it is a richer thing, one that circles and eddies, rises and falls, repeats upon itself.

And so this story—the story of my family—has many possible beginnings, or none: Mare Nostrum, Saint Augustine, Abd el-Kader, Charles de Gaulle, my grandparents, L’Arba, my father, my aunt, Zohra Drif, my mother, Albert Camus, Toronto, Cambridge, Toulon, Tlemcen, oh, Tlemcen: all and each a part of the vast and intricate web. Any version only partial.

Or I could begin with my birth, or my father’s birth or his father’s birth, or my mother’s or grandmother’s. I could begin with the secrets and shame, the ineffable shame that in telling their story I would wish at last to heal. The shame of the family history, of the history into which we were born. (How to forget that after attending the birth of his first grandson, my father, elderly then, tripped on the curb and fell in the street, a toppled mountain, and as he lay with the white down of his near-bald head in the gutter’s muck he muttered not “Help me” but “I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry”?) I could begin, of course, with the aloneness.

Or I could begin with the fact that the owner of our local pizzeria and our former next-door neighbor is an Algerian man whose surname is also the name of the provincial Algerian town of his ancestors, the same town in which my pied-noir grandmother taught at the girls’ school in her youth, in the years before she married—years that were, in her case, numerous, because she didn’t marry until her mid-thirties, then an age by which women were deemed unmarriageable. She might even have taught my neighbor’s grandmother or great-grandmother. Or I could begin with the fact that the beloved Lebanese friends of my grandfather’s prewar posting in Beirut include the great-uncle of a dear friend of mine in this American life almost a century later, whose daughter played with our son from the time they were round-limbed toddlers. Or I could begin with the angels on my father’s last journey to death, the witnesses to his many lives who appeared, sentinels and guides, along that final path, to guide him, the ultimately homeless, to his eternal home …

It doesn’t matter so much where this story begins as that it begins. And if, as I’ve come to understand, the story is infinitely expanding, rather than a line or thread, then wherever I start is merely that—not the beginning but a mere moment, a way of happening, a mouth …

From “This Strange Eventful History” by Claire Messud, published by W.W. Norton & Company. Copyright 2024 by Claire Messud. All rights reserved.

Get the book here:

“This Strange Eventful History” by Claire Messud

Buy locally from Bookshop.org

For more info:

CBS News

Gazan chefs cook up hope and humanity for online audience

Renad Atallah is an unlikely internet sensation: a 10-year-old chef, with a repertoire of simple recipes, cooking in war-torn Gaza. She has nearly a million followers on Instagram, who’ve witnessed her delight as she unpacks parcels of food aid.

CBS News

We interviewed Renad via satellite, though we were just 50 miles away, in Tel Aviv. [Israel doesn’t allow outside journalists into Gaza, except on brief trips with the country’s military.]

“There are a lot of dishes I’d like to cook, but the ingredients aren’t available in the market,” Renad told us. “Milk used to be easy to buy, but now it’s become very expensive.”

I asked, “How does it feel when so many people like your internet videos?”

“All the comments were positive,” she said. “When I’m feeling tired or sad and I want something to cheer me up, I read the comments.”

We sent a local camera crew to Renad’s home as she made Ful, a traditional Middle Eastern bean stew. Her older sister Noorhan says they never expected the videos to go viral. “Amazing food,” Noorhan said, who added that her sibling made her “very surprised!”

After more than a year of war, the Gaza Strip lies in ruins. Nearly everyone has been displaced from their homes. The United Nations says close to two million people are experiencing critical levels of hunger.

Hamada Shaqoura is another chef showing the outside world how Gazans are getting by, relying on food from aid packages, and cooking with a single gas burner in a tent.

Shaqoura also volunteers with the charity Watermelon Relief, which makes sweet treats for Gaza’s children.

In his videos online, Shaqoura always appears very serious. Asked why, he replied, “The situation does not call for smiling. What you see on screen will never show you how hard life is here.”

Before dawn one recent morning in Israel, we watched the UN’s World Food Program load nearly two dozen trucks with flour, headed across the border. The problem is not a lack of food; the problem is getting the food into the Gaza Strip, and into the hands of those who desperately need it.

The UN has repeatedly accused Israel of obstructing aid deliveries to Gaza. Israel’s government denies that, and claims that Hamas is hijacking aid.

“For all the actors that are on the ground, let the humanitarians do their work,” said Antoine Renard, the World Food Program’s director in the Palestinian territories.

I asked, “Some people might see these two chefs and think, well, they’re cooking, they have food.”

“They have food, but they don’t have the right food; they’re trying to accommodate with anything that they can find,” Renard said.

Even in our darkest hour, food can bring comfort. But for many in Gaza, there’s only the anxiety of not knowing where they’ll find their next meal.

For more info:

Story produced by Mikaela Bufano. Editor: Carol Ross.

See also:

“Sunday Morning” 2024 “Food Issue” recipe index

Delicious menu suggestions from top chefs, cookbook authors, food writers, restaurateurs, and the editors of Food & Wine magazine.

CBS News

A study to devise nutritional guidance just for you

It’s been said the best meals come from the heart, not from a recipe book. But at this USDA kitchen, there’s no pinch of this, dash of that, no dollops or smidgens of anything. Here, nutritionists in white coats painstakingly measure every single ingredient, down to the tenth of a gram.

Sheryn Stover is expected to eat every crumb of her pizza; any tiny morsels she does miss go back to the kitchen, where they’re scrutinized like evidence of some dietary crime.

Stover (or participant #8180, as she’s known) is one of some 10,000 volunteers enrolled in a $170 million nutrition study run by the National Institutes of Health. “At 78, not many people get to do studies that are going to affect a great amount of people, and I thought this was a great opportunity to do that,” she said.

CBS News

It’s called the Nutrition for Precision Health Study. “When I tell people about the study, the reaction usually is, ‘Oh, that’s so cool, can I do it?'” said coordinator Holly Nicastro.

She explained just what “precise” precisely means: “Precision nutrition means tailoring nutrition or dietary guidance to the individual.”

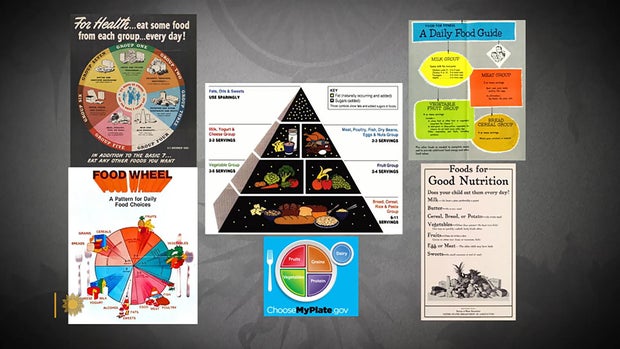

The government has long offered guidelines to help us eat better. In the 1940s we had the “Basic 7.” In the ’50s, the “Basic 4.” We’ve had the “Food Wheel,” the “Food Pyramid,” and currently, “My Plate.”

CBS News

They’re all well-intentioned, except they’re all based on averages – what works best for most people, most of the time. But according to Nicastro, there is no one best way to eat. “We know from virtually every nutrition study ever conducted, we have inner individual variability,” she said. “That means we have some people that are going to respond, and some people that aren’t. There’s no one-size-fits-all.”

The study’s participants, like Stover, are all being drawn from another NIH study program called All Of Us, a massive undertaking to create a database of at least a million people who are volunteering everything from their electronic health records to their DNA. It was from that All of Us research that Stover discovered she has the gene that makes some foods taste bitter, which could explain why she ate more of one kind of food than another.

Professor Sai Das, who oversees the study at Tufts University, says the goal of precision nutrition is to drill down even deeper into those individual differences. “We’re moving away from just saying everybody go do this, to being able to say, ‘Okay, if you have X, Y and Z characteristics, then you’re more likely to respond to a diet, and somebody else that has A, B and C characteristics will be responding to the diet differently,'” Das said.

It’s a big commitment for Stover, who is one of 150 people being paid to live at a handful of test sites around the country for six weeks – two weeks at a time. It’s so precise she can’t even go for a walk without a dietary chaperone. “Well, you could stop and buy candy … God forbid, you can’t do that!” she laughed.

While she’s here, everything from her resting metabolic rate, her body fat percentage, her bone mineral content, even the microbes in her gut (digested by a machine that essentially is a smart toilet paper reading device) are being analyzed for how hers may differ from someone else’s.

Nicastro said, “We really think that what’s going on in your poop is going to tell us a lot of information about your health and how you respond to food.”

CBS News

Stover says she doesn’t mind, except for the odd sounds the machine makes. While she is a live-in participant, thousands of others are participating from their homes, where electronic wearables track all kinds of health data, including special glasses that record everything they eat, activated when someone starts chewing. Artificial intelligence can then be used to determine not only which foods the person is eating, but how many calories are consumed.

This study is expected to be wrapped up by 2027, and because of it, we may indeed know not only to eat more fruits and vegetables, but what combination of foods is really best for us. The question that even Holly Nicastro can’t answer is, will we listen? “You can lead a horse to water; you can’t make them drink,” she said. “We can tailor the interventions all day. But one hypothesis I have is that if the guidance is tailored to the individual, it’s going to make that individual more likely to follow it, because this is for me, this was designed for me.”

For more info:

Story produced by Mark Hudspeth. Editor: Ed Givnish.

“Sunday Morning” 2024 “Food Issue” recipe index

Delicious menu suggestions from top chefs, cookbook authors, food writers, restaurateurs, and the editors of Food & Wine magazine.

CBS News

A new generation of shopping cart, with GPS and AI

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.