CBS News

The new middle-class retirement plan: Working into old age

A new glimpse into how middle-class people in the U.S. think about retirement is revealing some startling views about how long they expect to live and to work.

About half of middle-income Americans who are currently employed say they expect to work past age 65, according to a study from the Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies and the Transamerica Institute. While many say that is their preference, roughly 8 in 10 also cite financial pressures, including a shortfall in savings as well as worries that Social Security won’t provide enough financial support.

Transamerica defines “middle class” — a broad sociological term rather than a strict financial measure of income — as people earning $50,000 to $200,000 annually, which accounts for roughly 55% of U.S. adults.

“Many are saving for retirement, but the question is whether they are saving enough,” Catherine Collinson, the CEO of Transamerica Institute, told CBS MoneyWatch.

The perils of living longer

Middle-class households have saved a median of $66,000 in their retirement accounts, she noted, citing the survey data. But, as it grows, that nest egg might not prove to be enough to fund a retirement based on a person’s current age and lifestyle. It’s also a far cry from the $1.5 million that the typical worker said they’d need to fund a comfortable retirement, according to a Northwestern Mutual study published earlier this year.

To be sure, the number of 401(k) millionaires — people with at least $1 million in their retirement accounts — has recently surged to a new record, thanks to gains in the stock market, according to new Fidelity data. But that reflects only about 500,000 accounts, a fraction of the roughly 160 million people in the U.S. labor force.

Meanwhile, many middle-class workers are envisioning retirements that could stretch to 25 years or more, given their expectation of living to a median age of 90. A longer retirement requires socking more money away to fund more years out of the workforce.

“Longer human lifespans are prompting people to reconsider their life course including their time spent in the workforce relative to retirement,” Collinson added. “Many envision working longer and retiring at an older age which affords them more time to earn income and save, while others may be planning to fund longer retirements.”

“Not really a retirement”

Working past 65 is increasingly common in the U.S., with about one in five people over that age — approximately 11 million Americans — still holding down a job, according to the Pew Research Center.

Some, like Larry and Joyce Gesick, who are 77 and 66, respectively, recently told CBS News they continue to work because of tight finances. “It’s not really a retirement,” Joyce told CBS News. “It’s working every day.”

Only about 10% of Americans between 62 and 70 are both retired and financially stable, according to noted retirement expert Teresa Ghilarducci, whose book “Work, Retire, Repeat: The Uncertainty of Retirement in the New Economy” explores the financial pressures facing more Americans in retirement.

The reason, Ghilarducci says, is partly due to the current retirement system, which places the onus on workers to manage their own savings decisions through their 401(k)s and similar plans.

In an ideal world, these plans can work well for retirement planning. But, as Ghilarducci told CBS MoneyWatch earlier this year, it’s common for workers to experience job losses or financial stressors, disrupting their best intentions to put money away for retirement.

Even middle-class workers with access to 401(k)s aren’t always participating, with the Transamerica study finding that about 1 in 7 aren’t using their employer-sponsored plans.

And once workers have a 401(k), many are using the savings as a pre-retirement financial cushion, the analysis found. About one-third said they’d tapped their 401(k) or other retirement plan for a loan, early withdrawal or a hardship withdrawal, a share that Transamerica described as “concerning.” The top reasons for doing so were financial emergencies or paying off debt, the firm found.

Such withdrawals can sap the ability to save for a well-funded retirement and increases the risk of running short of money in old age.

Despite these challenges, about 7 in 10 middle-class Americans told Transamerica they’re confident they’ll be able to retire with a comfortable lifestyle. Many envision traveling, volunteering or taking care of grandkids once they’ve stepped back from work.

“The middle class has an upbeat vision about retirement as a time in life which brings opportunities for travel, spending time with family and friends, pursuing hobbies and more,” Collinson noted. “However, as a departure from long-standing notions, the middle class does not see retirement and work as being mutually exclusive.”

CBS News

A study to devise nutritional guidance just for you

It’s been said the best meals come from the heart, not from a recipe book. But at this USDA kitchen, there’s no pinch of this, dash of that, no dollops or smidgens of anything. Here, nutritionists in white coats painstakingly measure every single ingredient, down to the tenth of a gram.

Sheryn Stover is expected to eat every crumb of her pizza; any tiny morsels she does miss go back to the kitchen, where they’re scrutinized like evidence of some dietary crime.

Stover (or participant #8180, as she’s known) is one of some 10,000 volunteers enrolled in a $170 million nutrition study run by the National Institutes of Health. “At 78, not many people get to do studies that are going to affect a great amount of people, and I thought this was a great opportunity to do that,” she said.

CBS News

It’s called the Nutrition for Precision Health Study. “When I tell people about the study, the reaction usually is, ‘Oh, that’s so cool, can I do it?'” said coordinator Holly Nicastro.

She explained just what “precise” precisely means: “Precision nutrition means tailoring nutrition or dietary guidance to the individual.”

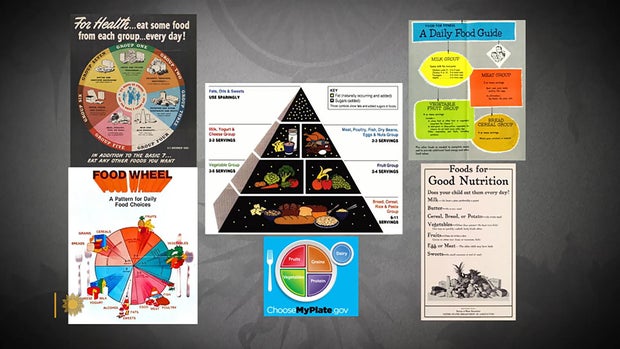

The government has long offered guidelines to help us eat better. In the 1940s we had the “Basic 7.” In the ’50s, the “Basic 4.” We’ve had the “Food Wheel,” the “Food Pyramid,” and currently, “My Plate.”

CBS News

They’re all well-intentioned, except they’re all based on averages – what works best for most people, most of the time. But according to Nicastro, there is no one best way to eat. “We know from virtually every nutrition study ever conducted, we have inner individual variability,” she said. “That means we have some people that are going to respond, and some people that aren’t. There’s no one-size-fits-all.”

The study’s participants, like Stover, are all being drawn from another NIH study program called All Of Us, a massive undertaking to create a database of at least a million people who are volunteering everything from their electronic health records to their DNA. It was from that All of Us research that Stover discovered she has the gene that makes some foods taste bitter, which could explain why she ate more of one kind of food than another.

Professor Sai Das, who oversees the study at Tufts University, says the goal of precision nutrition is to drill down even deeper into those individual differences. “We’re moving away from just saying everybody go do this, to being able to say, ‘Okay, if you have X, Y and Z characteristics, then you’re more likely to respond to a diet, and somebody else that has A, B and C characteristics will be responding to the diet differently,'” Das said.

It’s a big commitment for Stover, who is one of 150 people being paid to live at a handful of test sites around the country for six weeks – two weeks at a time. It’s so precise she can’t even go for a walk without a dietary chaperone. “Well, you could stop and buy candy … God forbid, you can’t do that!” she laughed.

While she’s here, everything from her resting metabolic rate, her body fat percentage, her bone mineral content, even the microbes in her gut (digested by a machine that essentially is a smart toilet paper reading device) are being analyzed for how hers may differ from someone else’s.

Nicastro said, “We really think that what’s going on in your poop is going to tell us a lot of information about your health and how you respond to food.”

CBS News

Stover says she doesn’t mind, except for the odd sounds the machine makes. While she is a live-in participant, thousands of others are participating from their homes, where electronic wearables track all kinds of health data, including special glasses that record everything they eat, activated when someone starts chewing. Artificial intelligence can then be used to determine not only which foods the person is eating, but how many calories are consumed.

This study is expected to be wrapped up by 2027, and because of it, we may indeed know not only to eat more fruits and vegetables, but what combination of foods is really best for us. The question that even Holly Nicastro can’t answer is, will we listen? “You can lead a horse to water; you can’t make them drink,” she said. “We can tailor the interventions all day. But one hypothesis I have is that if the guidance is tailored to the individual, it’s going to make that individual more likely to follow it, because this is for me, this was designed for me.”

For more info:

Story produced by Mark Hudspeth. Editor: Ed Givnish.

“Sunday Morning” 2024 “Food Issue” recipe index

Delicious menu suggestions from top chefs, cookbook authors, food writers, restaurateurs, and the editors of Food & Wine magazine.

CBS News

A new generation of shopping cart, with GPS and AI

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

“All hands on deck” for Idaho’s annual potato harvest

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.