CBS News

Gov. Newsom signs law to shed light on state storage of newborn DNA, prompted by 10-year CBS News California investigation

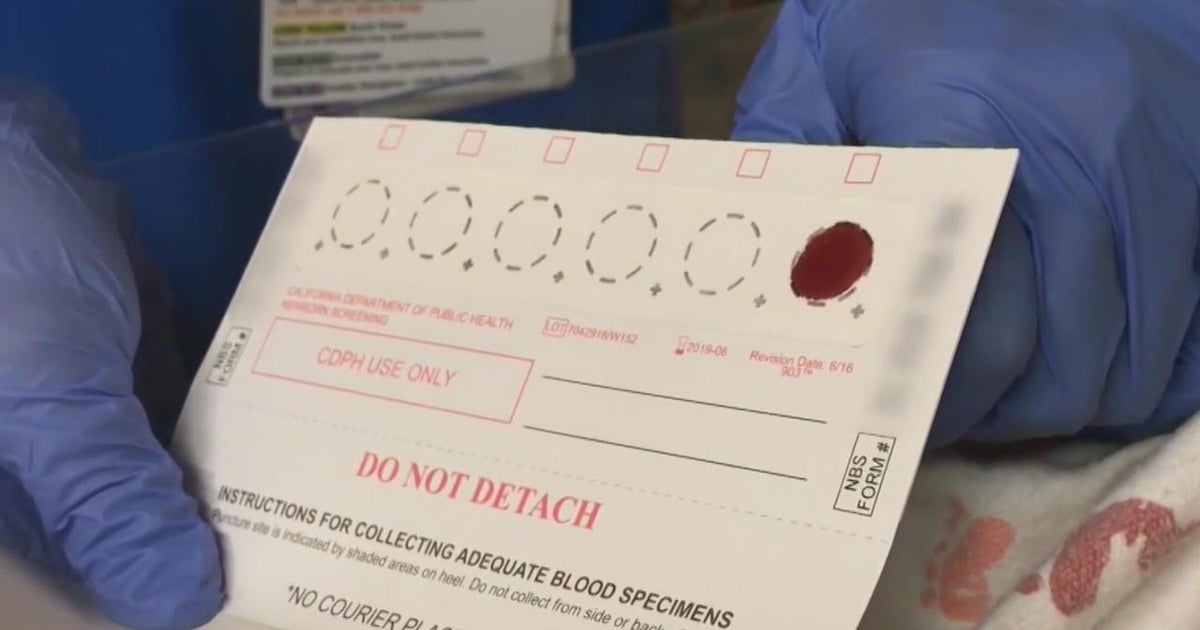

Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill (SB 1099) Wednesday prompted by a decade-long CBS News California investigation into California’s newborn genetic biobank.

We still won’t know who is using your DNA for research, or what the research is for, but the California Department of Public Health must now reveal the number of newborn DNA samples that California is storing and the number of DNA samples that the state sells to researchers each year.

California has stored blood spots from every baby born in the state since the 1980s. Researchers and law enforcement can use those DNA samples without your knowledge or consent.

If you’re related to someone who was born in California since 1983, a portion of your DNA is likely in the state’s massive Newborn Genetic Biobank. In response to our decade-long investigation, lawmakers introduced several bills this year that were intended to shed light on how the state is amassing and using California’s newborn DNA stockpile.

SB 1099 was the only bill to survive the legislative session.

While privacy advocates say it is a step in the right direction, recent amendments raise new questions about the appearance of state secrecy.

The initial bill was heavily amended to remove the requirements for the state to reveal which researchers are purchasing the DNA and what they are using it for.

Privacy advocates plan to try again next year.

See our continuing coverage on newborn blood spot privacy concerns here.

Learn more about newborn bloodspot storage and how to opt out of storage or research here.

CBS News

Democratic Congressman on the party’s messaging, focus

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

11/13: The Daily Report – CBS News

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

Opioid overdose deaths drop for 12th straight month, now lowest since 2020

Opioid overdose deaths have now slowed to the lowest levels nationwide since 2020, according to new estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This marks the 12th straight month of decline since a peak last year.

Around 70,655 deaths linked to opioids like heroin and fentanyl were reported for the year ending June 2024, the CDC now estimates, falling 18% from the same time in 2023.

Almost all states, except for a handful in the West from Alaska through Nevada, are now seeing a significant decrease in overdose death rates. Early data from Canada also suggests overdose deaths there might now be slowing off of a peak in 2023 too.

“While these data are cause for optimism, we must not lose sight of the fact that nearly 100,000 people are still estimated to be dying annually from drug overdose in the U.S.” said Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, in a statement.

Other types of drug overdoses beyond opioids are also slowing. While they make up a smaller share of overall deaths, overdoses linked to drugs like methamphetamine and cocaine are also showing signs of dropping nationwide following a peak last year.

“We are encouraged by this data, but boy, it is time to double down on the things that we know are working. It is not a time to pull back, and I feel very strongly, and our data shows, that the threat continues to evolve,” Dr. Allison Arwady, head of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, told CBS News.

Arwady pointed to a long list of factors that officials hope are contributing to the decline, ranging from broader availability of the overdose reversing spray naloxone, also known as Narcan, to efforts to ease gaps in access to medications that can treat opioid use disorder.

John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Trends in what health officials call “primary prevention” have also improved in recent years — meaning fewer people using the drugs to begin with. As an example, Arwady cited CDC surveys showing a clear decline in high school students reporting that they have tried illegal drugs.

The CDC and health departments have also gotten faster at gathering and analyzing data to respond to surges in overdoses, Arwady said, often caused by new so-called “adulterants” that are mixed in. Health authorities study this by testing blood and drug samples taken in the wake of surges, in search of potential emerging drug threats.

Agency researchers are now looking closer at what could be behind gaps in communities that are still not seeing slowdowns, Arwady said.

“Unfortunately, for the most affected groups, namely Native Americans and Black American men, the death rates are not decreasing and are at the highest recorded levels,” said Volkow.

Why are drug overdose deaths declining?

In the months since CDC data first began showing real signs of a nationwide change to the deadly record wave of opioid overdose deaths, experts have floated a number of theories to explain what caused the change.

“We had been seeing the numbers go down, on the national aggregate level, since last April, and we were skeptical and kind of holding our tongues. Then we started hearing from a lot of folks on the ground, frontline providers,'” said Nabarun Dasgupta, a senior scientist at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill who studies opioid overdose deaths.

Dasgupta led an analysis in September by the university’s Opioid Data Lab illustrating the nationwide scope of the downturn and probing a number of theories that might explain it.

Some explanations they dismissed as unlikely, like stepped-up law enforcement operations. Other ideas they judged as plausible, but complicated to prove, like a so-called “depletion of susceptibles” — essentially the epidemic burning itself out, as users either found ways to survive the influx of fentanyl or died — or the wider availability of naloxone.

Dasgupta said they received a flood of interest since their initial post proposing more theories, like new scanners that were deployed on the U.S.-Mexico border.

There are likely a number of factors all playing a role in the shift, Dasgupta says. But he said early data from research they are wrapping up now supports one leading explanation: a shift in the illegal drug supply.

“Our hypothesis is that something has changed in the drug supply. This kind of pronounced shift, something that happens suddenly, if numbers had suddenly shot up, we would definitely be pointing to a change in the drug supply to explain it,” said Dasgupta.

Amid its downsides, xylazine‘s rise might have led to less injection drug use, they speculate. Its longer high could also be reducing the number of times people use fentanyl each day.

“We’re not in our offices celebrating. We’re still losing too many people that we love. So I just want it to be very clear that with like a hundred thousand people still dying, that’s obscenely high,” he said.