CBS News

Texas execution is latest death penalty case to proceed despite shifting stances by law enforcement and prosecutors

Texas is planning to execute a death row inmate Thursday whose case has drawn widespread scrutiny, as doubts linger over whether his decades-old criminal conviction would stand up in court today — and whether he even committed the offense that back then was considered a crime.

Robert Roberson, 57, is scheduled to die by lethal injection Thursday for killing his 2-year-old daughter, Nikki Curtis, in 2002. Roberson, who has maintained his innocence, would become the first person in the United States put to death for a murder conviction tied to shaken baby syndrome if the execution goes ahead as planned.

His case is the latest in a string of instances where officials and prosecutors integral to the conviction and sentence of a condemned person have backpedaled on their original position about the individual’s guilt or punishment.

Roberson’s death sentence sparked controversy as it revived debate about shaken baby syndrome, a condition known in the medical community as abusive head trauma. It occurs when an inflicted head injury, caused by an adult forcefully shaking an infant or young toddler, results in serious brain damage that can be fatal. Many professionals in the fields of science and medicine now argue such a diagnosis is questionable and deeply flawed, because the definitions of shaken baby syndrome are vague and inconsistent, often overlapping with symptoms of other diseases that manifest on their own.

Criminal Justice Reform Caucus/Associated Press

“We need to reconsider the diagnostic criteria, if not the existence, of shaken baby syndrome,” researchers wrote in a 2004 paper on the condition published in The British Medical Journal. As more evidence to support points like theirs infiltrated mainstream medicine, at least dozens of people in the U.S. convicted of crimes linked to shaken baby syndrome were exonerated, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

As the science around shaken baby syndrome evolved, attorneys for Roberson have raised concerns about the legitimacy of his daughter’s diagnosis and how it influenced the jury’s guilty verdict. Evidence brought to light since then indicates the baby died from undetected pneumonia that developed into sepsis, and likely turned fatal after she was prescribed medication that would have hindered her ability to breathe, the attorneys said in court filings.

Compounding questions about the infant’s diagnosis is broad skepticism over the fairness of Roberson’s case. Brian Wharton, the lead detective who investigated the death of Roberson’s daughter in east Texas city of Palestine, helped convict him. Wharton now advocates vocally for the courts to review his conviction, citing changes in how science understands shaken baby syndrome and how law enforcement understands Roberson.

Wharton has said openly he believes Roberson is an innocent man.

Criminal Justice Reform Caucus/Associated Press

“For 20 years, I have thought that something went very wrong and justice was not served,” Wharton wrote in an opinion editorial for The Dallas Morning News in May. “I am asking for those who care deeply about justice to urge another look at this case.”

At the time of his arrest for murder, Roberson’s autism was undiagnosed. Wharton said in court filings that his team used Roberson’s behavior after the baby’s death as an indication of his guilt and a reason to charge him, but they would have viewed those actions differently had they known about his disorder. Furthermore, a substantial part of Texas’ argument for Roberson’s guilt hinged on the testimony of a nurse who claimed his daughter showed signs of sexual abuse, and that testimony has since been debunked.

Other recent death penalty cases clouded by doubts

Similar situations unfolded in two other capital punishment cases in the last three weeks alone, with one ending in an execution despite uncertainty about the inmate’s innocence and public calls from authorities to review his case. In September, Marcellus Williams died by lethal injection in Missouri after St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney Wesley Bell pushed to have his conviction overturned, in light of new evidence that DNA on the murder weapon belonged to someone else, not Williams, and the fact that racial bias may have influenced his trial.

Jim Salter/Associated Press

“Marcellus Williams should be alive today,” Bell said in a statement after Williams was executed. “There were multiple points in the timeline when decisions could have been made that would have spared him the death penalty. If there is even the shadow of a doubt of innocence, the death penalty should never be an option.”

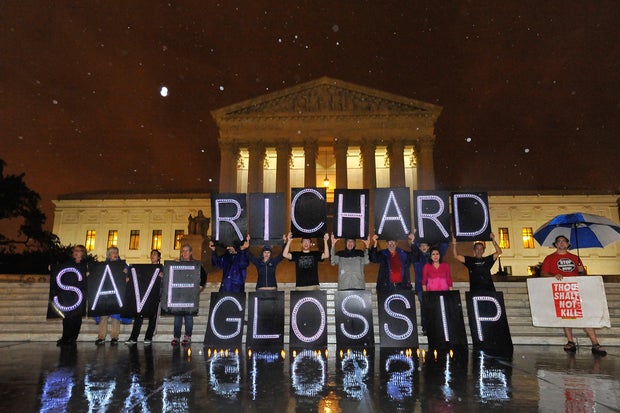

That argument echoes attorneys’ defense of Richard Glossip, an inmate on death row in Oklahoma, whose bid to block his ninth scheduled execution from happening and receive a new trial is being considered by the U.S. Supreme Court. Glossip’s conviction also hinged on questionable evidence, and an Oklahoma appellate court described fundamental elements of the state’s original case against him as “extremely weak.”

Glossip’s case has garnered national attention as the Oklahoma’s top prosecutor, Attorney General Gentner Drummond, rallied against his imminent execution in court filings and pushed for a new trial. Drummond in court filings has argued serious errors marred Glossip’s previous trial and may have swayed the verdict, including evidence suppression and false testimony from the prosecution’s key witness.

“Our system of justice places awesome powers and responsibilities in the hands of prosecutors,” Drummond wrote in one filing to the Supreme Court. “When those prosecutors themselves recognize that they have overstepped, that judgment cannot be dismissed as just another litigation position.”

Larry French/Getty Images

Glossip’s fate still hangs in the balance. Roberson’s potentially could, too, after a last-minute subpoena late Wednesday called him to testify before a Texas House committee that is examining the lawfulness of his murder conviction.

Most members of the state’s Republican-led House of Representatives previously called for a stay of Roberson’s execution, referencing a “junk science” law that should allow Texas prisoners to appeal their convictions based on scientific developments that could impact the evidence used to convict them. (The law was central to an appeal from Andrew Roark, a Texas man convicted in 2000 of injuring a child by shaking, who has been granted a new trial by the Texas Supreme Court.)

The state’s Department of Criminal Justice has not announced whether the execution will be postponed for the House committee hearing. A spokesperson for TDCJ told CBS News Wednesday night the department “has not seen the subpoena for inmate Roberson.”

“Should one be issued by the legislative committee and after we have an opportunity to review it, the agency will consult with the Office of Attorney General on the appropriate next steps,” the spokesperson said.

Meanwhile, Texas prosecutors urged the U.S. Supreme Court in a filing Wednesday evening to reject an emergency appeal brought by Roberson’s legal team in the wake of an earlier decision from the state’s pardon and parole board, which denied his request for clemency in a vote that recommended against delaying the lethal injection or commuting his sentence to life imprisonment.

Gov. Greg Abbott’s authority to grant clemency depends on the board’s recommendation, and their decision for Roberson means his hands are effectively tied without the court’s intervention. Abbott could still grant a 30-day reprieve without the board recommending it, but only once per case. The governor has commuted just one death sentence since taking office more than nine years ago, and in that time authorized 73 executions, more than any state in the country.

CBS News

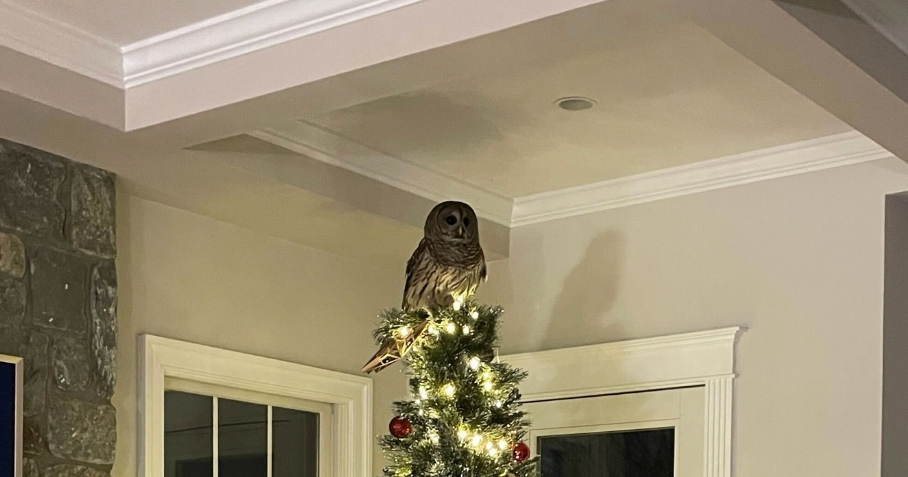

An owl came down a family’s chimney and perched on their Christmas tree: See the video

A Virginia family had an unexpected holiday visitor come down their chimney a week before Christmas.

A wild barred owl flew into a home through the house’s chimney, the Animal Welfare League of Arlington said on social media. Once in the home, the owl landed on the family’s Christmas tree, displacing the star that was already there to do so.

In a video clip shared by the Animal Welfare League, the owl can be seen swooping around the house, much to the delight of two young children who can be heard laughing at the bird. The owl explored the kitchen for a few moments, then returned to the Christmas tree.

“And back on the tree,” one of the children says.

Later in the video, the owl is captured and carried outside by an Animal League employee identified as Sergeant Murray. The bird flew back off into the night.

The Animal Welfare League said that capping chimneys during the winter will help prevent “curious critters,” including birds, squirrels and bats. Wildlife may use a chimney to hunker down and avoid cold air and wind during the winter, and some species may even use them as dens while giving birth, according to home solutions company HY-C. Capping a chimney can also prevent leaves, snow and other debris from falling down the shaft.

CBS News

How director Robert Eggers is reviving “Nosferatu” for a new generation

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

When a teen’s medication stopped working, he decided to try a surgery that could stop his episodes for good

When Isaac Klapper was 10 years old, he started having regular, daily episodes that caused his head to twitch and his eyes to turn to the side.

His pediatrician recommended a neurologist, who diagnosed Klapper with a movement disorder and prescribed medication. For five years, that kept the episodes at bay — but when he was a sophomore in high school, they returned, interrupting daily life and throwing his prior diagnosis into question.

Klapper spent the rest of his high school career missing out on milestones. He couldn’t drive, because of the chance he’d have an episode behind the wheel. It affected his social life and his ability to focus in class, because he always wondered when the next one might strike.

“It was pretty devastating,” said Klapper. “It was hard to handle. I just didn’t want to go anywhere because I was afraid of one happening.”

Meanwhile, his parents, Karen and Mark Klapper, watched him struggle and searched for answers. A neurologist in their home city of Toledo, Ohio was trying “medication after medication,” Mark Klapper said. After two years, there was no change, so the Klappers decided to look elsewhere for answers. A movement specialist said Klapper didn’t have a movement disorder: Instead, he was having frequent seizures. The family went to the Cleveland Clinic, where he was diagnosed with epilepsy.

Klapper Family

Dr. William Bingaman, a neurosurgeon and the vice-chairman of the neurological institute and head of the section of epilepsy surgery at Cleveland Clinic, had a new suggestion for treating Klapper’s seizures. Instead of more medications, he wanted to try a surgical approach, which, if successful, would stop the seizures for good.

Saying yes to brain surgery was one of the easiest decisions of his life, said Klapper, who is now 18.

“It was really a relief to just make a call, without hesitation,” Klapper said. “I was like, ‘I can’t live like this anymore.'”

Treating epilepsy with surgery

Epilepsy takes many different forms and results in multiple kinds of seizures. Klapper was having focal seizures, which are more minor episodes when electrical activity comes from one part of the brain, said Dr. Kerri Neville, a pediatric neurologist at University of Michigan Health C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, who was not involved in Klapper’s care. The seizures can include signs like jerking or twitching movements, changes in vision or other senses, and cognitive or mood changes, depending on what function the affected part of the brain controls.

Because of how broadly epilepsy can present, it can be “very, very challenging” to diagnose, Neville said. A movement disorder isn’t an uncommon misdiagnosis, she said. Once epilepsy has been diagnosed, doctors can start using medications to try and treat it: There are about 30 medications that exist to treat epilepsy, and about two-thirds of people can get complete control of the condition with one or two of those options. However, for the remaining third, seizures are still a problem.

Klapper Family

That’s where surgical options like the one Bingaman suggested come in. The surgical option used depends where the seizure activity is located, among other factors, Bingaman said. That’s found with brain scans and imaging.

The scans showed that Klapper had a “grape-sized abnormality” in his brain, Bingaman said. The abnormality was in his left cingulate gyrus, a major part of the limbic system that helps process emotions, regulate behavior and control automatic motor functions, and is “kind of buried in the middle of the brain,” Bingaman said. The abnormality could have been one of two things: cortical dysplasia, which means cells migrated unusually during brain development, or a brain tumor. The only way to determine the cause of the abnormality was to remove it.

Expanding access to surgical treatment for epilepsy

Both Bingaman and Neville said that while surgical treatment for epilepsy can be effective for patients who don’t respond to medication, it’s not a commonly used option. Epilepsy affects between 2 and 3% of the U.S. population, Bingaman said, and of those patients, about “40% or so may be surgical candidates.” But only about “two to three thousand” operations are done per year, Bingaman said, with the Cleveland Clinic alone handling about 500 cases annually, even though there are “a million people that are candidates for surgery right now.”

“It’s incredibly underutilized,” Bingaman said.

There’s no one reason why this option isn’t used more often, Bingaman and Neville said. Epilepsy can be misdiagnosed, as in Klapper’s case. It may also be hard to find the region of the brain where the seizure activity is originating. Doctors may not know to recommend surgery, Bingaman said. Patients may be wary about undergoing brain surgery, and going down the surgical route can also be expensive and time-consuming for patients and their families, especially if they don’t live near a center that does these operations regularly, Neville said.

Operating and finding answers

On March 8, 2024, Klapper was wheeled into surgery. The operation to remove the abnormality took about five hours, Bingaman said.

“It was a really long five hours for us,” said mom Karen Klapper. “It was a very long, scary few hours. It was a rough day for us.”

Klapper Family

Once the abnormality was removed, it was brought to pathologists for testing. They were able to determine that the abnormality was cortical dysplasia — not a brain tumor. That meant that now that the abnormality had been removed, Klapper likely wouldn’t have any more seizures.

Since then, Klapper has been seizure-free. More brain imaging and scans showed that the abnormality is gone, and now he’s turned his attention to applying for colleges.

“It felt really good to know that this probably going to stay for the rest of my life, like I’m not going to have to worry about this,” Klapper said. “I can just really focus on the future and how I’m not going to be tied down by this anymore. I can just go out and start my life.”

Twas the week before Christmas, and perched on the tree was an unexpected visitor as majestic as can be!

Twas the week before Christmas, and perched on the tree was an unexpected visitor as majestic as can be!