CBS News

Unexpected twist in Texas cold case murder probe: Victim was a bridesmaid in killer’s wedding

For Texas Ranger Brandon Bess, almost everything about the Mary Catherine Edwards case was different.

Ranger Brandon Bess: The thing that really got me about the case was, you don’t expect to have this beautiful, young, single, schoolteacher be murdered in her own home …. She was such a great person, came from such a great family.

Ranger Brandon Bess: It was an unusual crime scene. She’s over the bathtub and she’s obviously been sexually assaulted and handcuffed behind her back.

Natalie Morales | “48 Hours“ contributor: Were they … police-grade handcuffs?

Ranger Brandon Bess: Yeah. … Handcuffs have always been a key piece of this.

Texas Department of Public Safety

Jan. 14, 1995. It was a Saturday. Catherine, as most people called her, didn’t show up for a family lunch and she wasn’t answering her phone. When her mother and father went to check on her, they had to see what no parent ever should.

911 OPERATOR: What happened ma’am?

MARY ANN EDWARDS: We came over here and found her. … Please send someone over –

911 OPERATOR: OK, we’re sending someone ma’am. Is she — was she shot or what?

MARY ANN EDWARDS: Ah … we can’t tell.

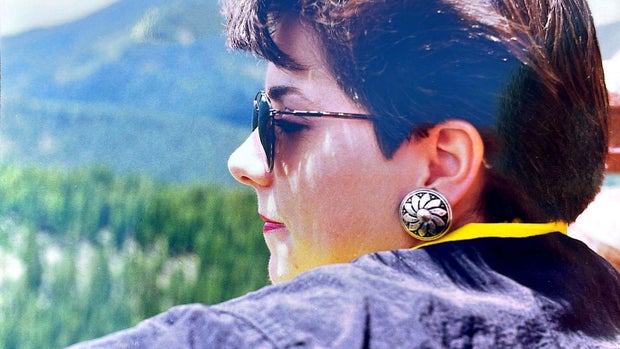

Catherine was 31. Dianna Coe remembers hearing the news.

Allison Edwards Brocato

The sisters, both schoolteachers, looked so much alike everyone had trouble telling them apart — especially their young students.

Heleniah Adams: Ms. Edwards … was my second-grade teacher.

Heleniah Adams remembers being in her classroom.

Heleniah Adams: Most of us grew up in … a pretty tough environment. … And being around Ms. Edwards was a joy.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: Originally, they believed that she might’ve been drowned, but there wasn’t enough fluid in her lungs, so then it kind of became a suffocation by compression.

Heleniah Adams: I just remember being told that our teacher wouldn’t make it to class that day … Everyone just crying.

Jefferson County D.A.’s Office

Dianna Coe: My mom is the one that told me … And so she said, “have you not heard about Catherine?” … and I go, “my Catherine?”

She had been friends with Catherine and her twin sister Allison since middle school.

Dianna Coe: I was new to the area. … so I knew no one. … and they … just started talking to me … asked me my name … and we were friends from that point forward.

The sisters, both schoolteachers, looked so much alike everyone had trouble telling them apart — especially their young students.

Heleniah Adams: Ms. Edwards … was my second-grade teacher.

Heleniah Adams remembers being in her classroom.

Heleniah Adams: Most of us grew up in … a pretty tough environment. … And being around Ms. Edwards was a joy.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: Originally, they believed that she might’ve been drowned, but there wasn’t enough fluid in her lungs, so then it kind of became a suffocation by compression.

Heleniah Adams: I just remember being told that our teacher wouldn’t make it to class that day … Everyone just crying.

Early investigators could not piece together what happened, but those police-grade handcuffs were a big clue.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: It was almost talked about like a ghost story around a campfire.

Aaron Lewallen is a detective with the Beaumont Police Department.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: Maybe it was somebody in law enforcement or somebody in security. … Could it have been somebody that we knew?

In the weeks after the murder, police focused on tracing the serial numbers of the handcuffs but came up empty.

They also zeroed in on an old boyfriend — David Perry.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: They focused on him early on because … there was no forced entry.

But Perry was out of town that night. He gave a DNA sample and it was not a match.

David Perry: I wasn’t there. It’s not me.

The crime scene DNA stayed well preserved and the years dragged on and on — until forensic science changed.

FINDING THE KILLER’S RELATIVES: DNA LEFT BEHIND AT THE CRIME SCENE IS TESTED

By 2018, there was a way to take the DNA left at a crime scene and search for biological relatives. A program — Gedmatch — scarfs up all the DNA from people who agree to share it with law enforcement and upload it when they use sites like Ancestry.com and 23andMe.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: Ranger Bess approached me … and he asked if I thought we had a case that would fit the bill for that type of investigation. I said, “absolutely. I know the perfect case for this.” And it was the Catherine Edwards case.

So, in April 2020, the DNA from Catherine Edwards’ crime scene went to Othram, a lab outside of Houston, for testing.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: There, they would give us familial matches. And from there, we would start trying to build a family tree to get us closer to our suspect.

But the number of names to pursue was overwhelming.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: When the family tree began to grow beyond my computer screen, (laughs) I started to get a little bit confused. And that’s when … Tina jumped on board.

Det. Aaron’s Lewallen’s wife, Tina Lewallen, an auto crimes detective, began using her off hours to help sort through it.

Det. Tina Lewallen: The matches were all Cajun.

Natalie Morales: Cajun … ancestry –

Det. Tina Lewallen: Yes.

Natalie Morales: — coming from the Louisiana area.

Det. Tina Lewallen: Yes.

Natalie Morales: Specifically.

Det. Tina Lewallen: … particularly Kaplan, Louisiana.

So Det. Tina Lewallen went back to Catherine’s journals looking for clues.

Det. Tina Lewallen: … to see if I could see a Cajun name that jumped out to me. … I did find a few French names and they were quickly eliminated and nowhere in our tree.

And as she was building out the branches, one of the names on the family tree kept coming up: LaPoint.

Det. Tina Lewallen: I’m researching the matches and building my trees and you’re researching other people’s trees … I kept noticing Shera LaPoint — had built that tree, and then I’m working some more, I do some more research. Well, Shera LaPoint built this tree. And I’m like, is she related to our suspect? … I had no idea who she was.

And when they called her, they found out LaPoint had been building her family tree.

Shera LaPoint: It was my family’s DNA kits that I had uploaded to GEDmatch.

And then they found out something that changed the course of the investigation. LaPoint was known professionally as “The Gene Hunter” and already skilled at working these cases. She’d identified one of the women buried along Interstate Highway 45 in the Texas killing fields case.

And she agreed to lend her expertise.

Shera LaPoint: I told him that I was willing to help.

Even if it meant taking a hard look at her own relatives.

Shera LaPoint: It was kind of scary because I’m putting my own second cousins in this tree and I’m thinking, oh my gosh, you know, could one of my grandfather’s sister’s grandchildren have — have done this, they lived here in Texas.

It was a complicated, multilayered process using publicly available DNA, birth and death records — finding parents, siblings and cousins.

Shera LaPoint: As you build those trees, you look for information that … is pertinent to the case that you’re working on. We had a tag for people who were in Beaumont … She was a teacher. As you build tree, you look at people who are in education.

The tree grew up and down and sideways – there were almost 7,500 names.

Shera LaPoint: That’s a lot of hours, a lot of work and a lot of people in a family tree.

All the while, Det. Tina Lewallen hardly slept, working through most nights — knowing there was a killer still out there.

Det. Tina Lewallen: Every day counted; every day mattered … I needed to get it solved.

THE FAMILY TREE PAYS OFF: IDENTIFYING A SUSPECT WITH A SURPRISING CONNECTION TO MARY CATHERINE

Hunkered down at their computers day after day, constantly back and forth on the phone, Det. Tina Lewallen and genealogist Shera LaPoint are quickly becoming great partners.

Det. Tina Lewallen: She was a team player from jump. Never had met me. … we talked so often that we became friends.

Natalie Morales: Best buds.

Shera LaPoint: Best buds. I don’t know what else to say.

And when they needed DNA, they turned to Det. Tina Lewallen’s husband, Det. Aaron Lewallen, and Texas Ranger Brandon Bess.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: So, from that point, me and Brandon Bess would drive around Texas and go talk to these people.

Ranger Brandon Bess: Convincing someone … to give their DNA up, to give a piece of themselves up to you in a homicide investigation can be very difficult.

Ranger Brandon Bess: When we would sense, um, anxiety in someone, Aaron would immediately tell them, “hey, who do you want to play you in the movie …”

Ranger Brandon Bess: And they would look at Aaron like he was crazy … and say, (laughs) um, “what are you talking about.” “Well, this guy’s a Texas Ranger, everything they do turns into a movie. Who do you want to play your role in this movie?” (laughs) That calmed them down every time … and I of course threw out there, “hey, I’ve already got Brad Pitt. So, you know, you can’t — you can’t be Brad – cause Brad’s playing me.”

Natalie Morales: Was there ever a time though that somebody actually thought … my uncle may actually be a killer. Who knows?

Ranger Brandon Bess: In every one of these cases that I’ve worked using DNA and genetic genealogy, you have at least one person, usually two or three that says, you know what, I had that weird Uncle Joe …

Once the uploads were compared to the killer’s DNA, if the amount of shared genetic material was low, they knew it was a dead end.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: Cause there were times when we would come across a name and I’m like — you get that that butterflies in your stomach … like, “hey, maybe this is our guy” … And then … turns out it’s not our guy.

After almost three month of ups and down and nearly nonstop work, LaPoint hit paydirt.

Shera LaPoint: It was about 10:30 at night.

She was working a family line very distantly related to her own.

Shera LaPoint: It was a very common Cajun name, Thibodeaux. … I got to a couple who were in Beaumont … I was able to see from, uh, records that they had two sons.

This was a major lead: a family, in Catherine’s town, with two sons who went to Forest Park High – the same school Catherine did — at around the same time.

Shera LaPoint: I put the names in the tree and I messaged Tina and I said, um, “there’s a couple in Beaumont.”

Shera LaPoint: I’m tired, I’m going to bed. And I turned my cellphone off and I fell asleep on the sofa … and when I woke up the next morning, my phone had just blown up.

Natalie Morales: And it was you on the other end?

Det. Tina Lewallen: Yes.

Natalie Morales: What were you saying?

Det. Tina Lewallen: This is them. We found them. Just didn’t know which one.

Natalie Morales: OK … it’s either Michael Foreman or Clayton Foreman. What did you do to — to figure that out?

Dianna Coe

Det. Aaron Lewallen: The first name I ran was Clayton … And when I came across his prior conviction for the sexual assault, the hair on the back of my neck stood up. I’m like, “this is our guy.”

In 1981, a 19-year-old woman told police that Clayton Foreman bound her hands and raped her. She had also gone to Forest Park High School where Clayton was the manager of the football team. Clayton Foreman was convicted but was given probation and paid a fine.

Natalie Morales: But he did not have to give a DNA sample at that time.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: No. This was back in the early ’80s. We didn’t have sex offender registry, uh, no DNA database.

And then they found another connection: it went all way back to Dianna Coe, Catherine’s friend from middle school.

In high school, Coe fell madly in love. Her boyfriend had graduated three years ahead of her, and they got engaged.

Dianna Coe: He was so kind. … He had the most wonderful personality.

And when she started planning her wedding, she immediately turned to her old friends Catherine and Allison.

Dianna Coe: And they were one of the first ones I thought of as, uh, bridesmaid and — and I asked them and they said yes.

And the groom? The man Coe married back in 1982? Now he was their number one suspect: Clayton Foreman.

Natalie Morales: She in fact did know him.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: Yes.

In hindsight, there were signs. When Coe found out about Clayton Foreman’s legal troubles, the wedding was less than three months away.

Dianna Coe: … and … the wedding invitations had already been mailed out.

Dianna Coe: And I said, “rape?” I said, “oh, there’s no way.”

Dianna Coe

But she never got any details and her fiancé explained it away.

Dianna Coe: … he kept telling me, it — it was a big misunderstanding … And so in my mind, I thought, well, he must be telling the truth because if he got arrested, he’s not in jail.

Natalie Morales: But you didn’t really believe it was rape?

Dianna Coe: Right.

Coe’s sister, Anne Anderson, and her brother, Scooter Daleo, were not so sure and neither were their parents who wanted her to call it off.

Scooter Daleo: And I said, well, “Dianna, why don’t you just wait?” … And she didn’t wanna wait. She wanted to marry Clay. She was in love with him.

Anne Anderson: … she’s believing him and she’s wanting to get married, then — then we have to support as a family.

Dianna Coe: And he was like, I’m so, so sorry. … I love you. I want us to be married. I want us to have a family. … And so, I was like, OK, you know. So I went — I went through with it.

Dianna and Clayton Foreman stayed married for a little more than 11 years and they had a son. The relationship began to fray over Foreman lying about their finances and it ended after he had an affair. And looking back, Coe can see that he had an unhealthy fascination with police officers and the tools of their trade — like handcuffs.

Dianna Coe: I remember that he had ordered those handcuffs. … Well, he had ’em hung over the rearview mirror … And I — I didn’t think anything of it.

When Catherine was killed, they were divorced, but Coe remembers calling her ex-husband to talk about it.

Dianna Coe: I think I was, you know, crying and I said, “oh, my God,” I said, “somebody has murdered Catherine.” And — and he goes,” oh, really?” Just like no emotion … When we hung the phone up, I can remember ’cause I was like kind of squinting and kind of like going, God, that’s kind of odd.

With all the mounting evidence, Foreman needed to be found. He was 60 and no longer living in Beaumont. They quickly tracked him to Reynoldsberg, Ohio.

Natalie Morales: What was he doing there?

Det. Aaron Lewallen: He was an Uber driver at the time. … I was able to send a lead, uh, to a field office up there … and basically did what we call a trash run.

Natalie Morales: You need to collect a piece of DNA so that you can ensure that it’s the — the right guy, right?

Jefferson County D.A.’s Office

Det. Aaron Lewallen: Correct. Uh, so, that’s what they did. … They surveilled his house … and then went and snatched a bag of trash … and sent it to me.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: Uh, so, I brought that stuff to Houston, to the DPS crime lab. And from there they tested it.

The likelihood that the DNA belonged to Clayton Foreman was a big number — 461 septillion. It doesn’t get better than that, says LaPoint.

Shera LaPoint: I mean, you can’t fight those odds. You cannot fight those odds.

And that was all they needed.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: And I got a text from a — a DPS lab technician. And she said, “go get his ass.”

Det. Aaron Lewallen and Ranger Bess were about to hop a plane to Ohio, ready to face the man they felt sure had killed Catherine.

And while they’re doing that, Det. Tina Lewallen pays a visit to Coe.

Natalie Morales: Did they tell you we had — they had DNA, though? Tina told you that?

Dianna Coe: Oh, yeah. Yeah.

Dianna Coe: And I just went (gasps) “Oh my God, please don’t tell me it was Clay –”

Dianna Coe: I almost fell to the ground. … I was just like, “oh, my God.” Like, “oh, God, I can’t believe he’s done this.”

CONFRONTING CLAYTON FOREMAN

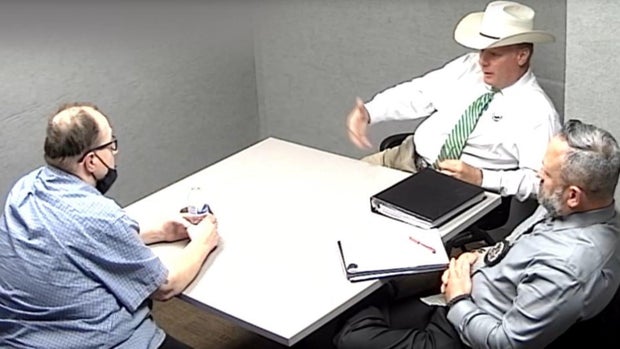

When Ranger Bess and Det. Aaron Lewallen arrive at the Franklin County Sheriff’s Office to confront Clayton Foreman, they have a cover story – it’s about a lost item from one of Foreman’s Uber rides.

Ranger Brandon Bess: We go in under the — uh, under the ruse of someone had left, uh, a purse in his car. So he came in — voluntarily to talk about a purse that was in the car.

It was April 29, 2021 — 26 years after Catherine Edwards was murdered, and they are sure they are sitting in front of the man who murdered her.

RANGER BESS (Foreman interview): We’re asking you to visit with us about a crime that we’re investigating. OK?

Natalie Morales: Did he immediately go, uh-oh, you know —

Det. Aaron Lewallen: No, he didn’t

RANGER BESS (Foreman interview): So, the crime that we’re looking at is the murder of Mary Catherine Edwards. … and she was murdered in 1995.

Natalie Morales: I guess he pretty quickly realized he wasn’t there to give up a purse.

Ranger Brandon Bess: He did …

Dianna Coe

RANGER BESS (Foreman interview): And we found a picture of — a wedding picture that she and her sister, uh —

DET. AARON LEWALLEN: Allison.

RANGER BESS: — Allison were actually in your wedding.

CLAYTON FOREMAN: Right.

RANGER BESS: And —

CLAYTON FOREMAN: 1982.

RANGER BESS: — 82. OK.

RANGER BESS: Do you ever remember anyone ever coming to you — about that crime?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: No.

RANGER BESS: Were you aware of the crime even?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: No.

RANGER BESS: You didn’t know the crime occurred?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: No, sir.

RANGER BESS: OK.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: … we backed him into a bunch of hard corners. He claimed that he didn’t even know that she was dead.

Jefferson County D.A.’s Office

RANGER BESS (Foreman interview): You didn’t know that, um, Catherine Edwards was murdered?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: No, sir. Did not.

RANGER BESS: Do you remember them from school? Do you remember the girls from school?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: Not really. Because they were freshmen.

RANGER BESS: When you were a senior?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: Yes, sir.

RANGER BESS: OK.

RANGER BESS (Foreman interview): So, on Mary Edwards, Mary Catherine Edwards. Um, didn’t know her well? Did you ever visit with her at all?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: No.

RANGER BESS: Um, did you ever go in her house at all? Any house that she ever lived in?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: No.

RANGER BESS: OK.

David Perry

Det. Aaron Lewallen: You know, “did you know where she lived?” No. Had no idea.

Natalie Morales: So, and he’s denying, denying …

Ranger Brandon Bess: He is denying … you know, in these DNA cases, when you — whether you’re gonna get a confession or not, you wanna build up that background of, “hey, did you know them?” Number one.

RANGER BESS (Foreman interview): Did y’all have much acquaintance with them or was it just like a high school friend thing?

RANGER BESS: How did you know them?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: I think they were bridesmaids for my — my ex-wife.

RANGER BESS: That’s right.

RANGER BESS: Did you ever go on a date?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: Never dated.

Ranger Brandon Bess: All the way up to, “did you ever have sex with this person?”

RANGER BESS (Foreman interview): Never obviously had sex with her.

CLAYTON FOREMAN: No.

RANGER BESS: Never?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: Never.

Ranger Brandon Bess: Did you go to college together? Did you do all — everything was a no,

Det. Aaron Lewallen: And we had those denials several times. And then, so, towards the end of the interview, we asked him, well, if all those things are true, can you explain how your DNA ended up on her and on her bed?

RANGER BESS (Foreman questioning): Do you understand DNA?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: Mm-hmm.

RANGER BESS: And do you understand how DNA works? You understand you’re made of DNA?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: Right.

RANGER BESS (referencing Det. Aaron Lewallen): He’s made of DNA. I’m made of DNA.

Ranger Brandon Bess: I think that Foreman knew enough about DNA that he thought he would’ve been caught already. He knew that he had never submitted his DNA —

Ranger Brandon Bess: He had no clue that he was going to be arrested that day.

RANGER BESS (Foreman interview): Clay, I’mma level with you. Right here and now, I want you to hear me real close.

CLAYTON FOREMAN: All right, sir.

RANGER BESS: That crime scene was processed really well. … and your DNA was on Catherine’s bed and was inside Catherine.

CLAYTON FOREMAN: OK. I mean, I don’t know how it got there, but, if you say it was there.

RANGER BESS: There’s only one way for it to get there.

CLAYTON FOREMAN: OK.

RANGER BESS: Um, and that’s by you putting it there.

CLAYTON FOREMAN: OK.

RANGER BESS: Do you understand that?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: Uh —

RANGER BESS: Do you understand the implications of that? The day that she died, the night that she died, your DNA is in her and your DNA is on her bedspread. … Now I don’t want you to say anything right this second. I want you to think about the next words that come out of your mouth. I want you to think very hard about that. … OK?

RANGER BESS: There’s two people that know that story. … You’re one of them and she’s the other. And she can’t talk.

CLAYTON FOREMAN: Mm-hmm.

RANGER BESS: What I ask you is now to be honest with us completely and tell us, you know, how did that happen?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: I’m not going to say anything. I probably need an attorney now, I think.

RANGER BESS: You probably need one or you do need one?

CLAYTON FOREMAN: Well, if you’re saying I did that, then I’ll probably need an attorney to talk to.

RANGER BESS: Well, that’s all we got then. We’re going to let you walk out of that door just like we told you.

Ranger Brandon Bess: It’s a grainy video, but you can probably see us grinning at each other — that he thinks he’s walking outta here, he thinks he’s fixing to leave here.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: So, as he got out, down the hallway, headed towards the elevator, we stopped him and arrested him for the murder of Catherine Edwards.

And after all those years and all that work, Aaron Lewallen and Brandon Bess had one thing left they needed to do.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: Uh, if you remember back when we were talking about the crime scene, she was handcuffed. … So, we had talked to the DA’s office beforehand and got permission to use those handcuffs.

Brandon Bess

The very handcuffs that bound Catherine the night she died.

Natalie Morales: How did it feel to put those handcuffs on him?

Ranger Brandon Bess: Very good … it’s a moment I’ll never forget … you feel like you got to do something for Catherine there .,.. you know, like physically got to do for her, is take those cuffs that bound her when she was murdered and put them back on the guy that murdered her. It’s — you know, it may seem small to some, but it was a really big deal to us, and it felt good.

Even though they’d had their suspicions about him, when Det. Tina Lewallen broke the news to his ex-wife Dianna Coe that Clayton Foreman was arrested for the murder of Catherine Edwards was still a shock.

Scooter Daleo: … she calls me … And she says, “Clay murdered Catherine.” And I said, “do what?”

Anne Anderson: Your brain doesn’t — because it — it knows him as a person, as a — as — as somebody that you — you know, your brother-in-law or your brother.

Dianna Coe: That was — that was — that was hard. … I thought of Allison … And I just — I — I just couldn’t believe it. … my — my thought immediately went to Allison and I just said … “Allison. … oh, my God, she’s gonna hate me.”

But Det. Tina Lewallen assured Coe, on the contrary, that Allison was very concerned for her.

Dianna Coe: And — and she said, she’s – “she’s worried for you.” And she said, “do not — do not think that.”

THE TRIAL OF CLAYTON FOREMAN

On March 12, 2024, nearly 30 years after Mary Catherine Edwards was found dead in her town house, Beaumont prosecutor Patrick Knauth and his colleagues Mike Laird and Sonny Eckhart are ready for trial.

Mike Laird: This is not going to be easy, uh, for a lot of people, cause it’s been a long time coming. … you gotta remember this happened in 1995.

MIKE LAIRD (in court): You’re gonna get to learn a lot about DNA.

And they are extremely confident about their case against Clayton Foreman.

JUDGE JOHN STEVENS (in court) : Mr. Burbank, do you wanna make an opening statement at this time?

TOM BURBANK: No, your honor.

Tom Burbank Is defending Foreman.

Patrick Knauth: He didn’t really have anything. And he knew it.

The prosecution calls Catherine’s twin sister Allison.

Patrick Knauth: We wanted to remind everyone, this is about Catherine and her family. And that’s the way we wanted to start off with …

KFDM/Pool

Here at 60, sitting before them, was the spitting image of what could have been.

ALLISON EDWARDS BROCATO (in court): That is a picture of my sister Catherine.

Reliving the day she lost Catherine.

ALLISON EDWARDS BROCATO (in court): … and then the next thing we know, you know, my mom and dad drove up (crying) and told us what — I mean, they — there were no words. She was dead. That was all that mattered. … I didn’t know how, what or anything. … I didn’t know what happened to her, it was just that she was gone was all I knew.

The pain and the loss still so palpable.

ALLISON EDWARDS BROCATO (in court): Four years later, I had a daughter, and her name is Catherine (crying), Catherine Ann after my sister and she never got to know her. … That’s the hardest part …

Heleniah Adams, Catherine Edwards’ student when she was 7, is now 37 and sat in the courtroom nearly every day.

Heleniah Adams: It was times … when they would show photos or when they showed the videos of her on the floor … it was as if your heart was breaking all over again.

Detective Tina Lewallen and genealogist Shera LaPoint, along with other crime lab technicians, walk the jury through the process of the genealogy and the DNA match.

Ranger Bess and Det. Aaron Lewallen go through the final stages of the investigation. All carefully coordinated to make the chain of evidence airtight.

And on the last day, the prosecution calls all the women who had been scarred by Foreman – and were alive to say so.

TOM BURBANK (in court): He was your supervisor?

KRISTY WEIMER: That’s correct.

An old co-worker.

KRISTY WEIMER (in court): Whenever I opened up the drawer, there was a pair of handcuffs.

A former fiancée who found pictures of young girls.

TERESA BREWER (in court): He said to me that he had them so that he could fantasize about taking their virginity.

His ex-wife, Dianna Coe, who agreed to testify.

TOM BURBANK (in court): Did you think at the time you were in love with the defendant?

DIANNA COE: Yes.

Natalie Morales: When you saw him at trial … How hard was that for you?

Dianna Coe: That was very hard … And uh — it was very embarrassing to me and — and I do feel ashamed.

And it was during the trial that Coe learned about what really happened to that 19-year-old woman in the months before she and Foreman married.

Dianna Coe: … it was the most horrific thing that I could have ever heard. … I couldn’t imagine what she went through and was so brave to get up and say what she said.

She was the final witness, returning to the night her car got stuck and Foreman — falsely claiming he was a policeman — offered to help.

PAULA RAMSEY (in court): First he — he tied my hands back.

MIKE LAIRD: He tied your hands behind your back?

PAULA RAMSEY: Yes.

MIKE LAIRD: Did he threaten to cut your throat if you didn’t?

PAULA RAMSEY: Yes.

MIKE LAIRD: This whole thing took a while, didn’t it?

PAULA RAMSEY: Yes, sir. I’m sorry.

MIKE LAIRD: What happened then?

PAULA RAMSEY: He — he took me home.

MIKE LAIRD: Did he say something that — that you felt was odd?

PAULA RAMSEY: Yes. He said three things. He said, “stop crying, I’m sorry, I hope I didn’t hurt you.”

And there was another women who did not testify but went on the record. An alleged victim of Foreman’s violence — also a high school friend of Dianna Coe who did not press changes. She told investigators Foreman attacked her from behind and put a gun to her head.

Pat Knauth: She had indicated back in ’85 or ’86 that he had, uh, come to her apartment and knocked on the door and told her that he was having financial and marital problems with Dianna, and he needed somebody to talk to. And so … she let him in.

Prosecutors suspect Foreman used a similar ruse the night he appeared at Catherine Edwards’ door.

Pat Knauth: That’s the way we thought he got to Catherine, ’cause Catherine was very, very Christian, very giving, very naïve … And that’s a wonderful thing to be, except when you’re faced with Clayton Foreman.

Dianna Coe: I’ve always wondered, did he say something about me? Hey, it’s Clay and, you know, I need to talk to you about — something about Dianna. It’s always — I’ve always wondered, but I thought I’ll never know.

After seven days of prosecution testimony, the defense calls no witnesses, and attorney Burbank closes.

TOM BURBANK (in court): You heard different things in reference to sex things and stuff like that, okay, still doesn’t make him a murderer.

TOM BURBANK (in court): You may not like him cause of what people said, but I submit to you, they have not proven murder beyond a reasonable doubt.

The prosecution wraps up its case.

PAT KNAUTH (in court): And it’s so easy to believe that evil doesn’t exist … It is here in this courtroom here today.

PAT KNAUTH (in court): These are things I wish I didn’t know exist and I’m sorry I had to talk to you about it, but I didn’t bring us here, he did.

Now it would be up to a jury to decide Clayton Foreman’s future.

Knauth wants them to remember Catherine Edwards didn’t have one.

PAT KNAUTH (in court): And I do pray that Mike and I and Sonny have done a good job for Catherine, and you. I hope we’ve done our job.

THE AFTERMATH: LOOKING BACK

It takes less than an hour for the jury to come back with a verdict.

Clayton Foreman is found guilty and sentenced to life for the murder of Catherine Edwards.

Larry Delcambre: It didn’t take long ’cause all the evidence was there, … once it got into the DNA …more or less sealed it for him.

Larry Delcambre, juror No. 2, says he and his fellow jurors had very little to talk about.

Larry Delcambre: He had no defense that it wasn’t him … there’s no denial there.

Heleniah Adams: It felt like, hey, this thing does work.

For Heleniah Adams – finally some justice for a favorite teacher after all.

Heleniah Adams: I wanted to close that door, finally. She meant so much to me.

Natalie Morales: And when you heard those words guilty, what was that like for you?

Det. Aaron Lewallen: We did it.

Natalie Morales: Was it — was it an emotional, we did it?

Det. Tina Lewallen: This whole case was emotional.

For detectives Tina and Aaron Lewallen, genealogist Shera LaPoint and Ranger Brandon Bess, it was the ending they’d all worked for, but it left lots of room for reflection.

Shera LaPoint: And I think the justice system has worked and he’s where he needs to be. … But to say that that’s honestly justice for Mary Catherine, it’s frustrating to know that he lived a life … and she should have been able to — to live a life and have children and go on. That is frustrating.

Det. Tina Lewallen: I never used the word closure. I never used the word justice.

There’s no justice. He got to live 26 years that he got to get married. He got to have kids. She did not. There’s no justice.

Ranger Brandon Bess : I don’t — I don’t believe there is such a thing as closure. … Not on this earth.

Bess always wanted a confession, they all wanted to know why.

Ranger Brandon Bess: 70% of the time you’re not gonna get that and — and 100% of the time you’re not gonna get the whole story anyway.

Det. Tina Lewallen: We all wanted those answers and because he was spineless and didn’t talk to us or give us any information, we’ll never know the details behind it.

And everyone was still reeling, asking themselves how it was that Clayton Foreman walked among them and no one saw his monstrous core — all those years hiding in plain sight.

Det. Tina Lewallen: So, when we identified him, I actually have mutual friends with him that were in shock. … They could not believe it was him because they knew he was such a nice guy. He had fooled so many people for so long.

Det. Aaron Lewallen: I personally believe that there are more victims out there. We just hadn’t found them yet.

Dianna Coe: I find it hard to believe that he has not … assaulted other people. I — I really feel with — all my — with all of my being, I feel that there are others.

Scooter Daleo: I believe that.

Anne Anderson: I believe it ,too.

Natalie Morales: And how do you think he was able to conceal this darker side?

Anne Anderson: That’s the part I cannot — I can’t — figure that out.

Dianna Coe: I can’t — Uh, I — I don’t understand it. I don’t know how he could. Like I always say, it’s like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Larry Delcambre: I have my own speculations. I think somebody — I think some people are demon-possessed or — or demon-influenced, cause that’s pure evil. There’s nothing else you can explain. That’s just evil.

Dianna Coe: I was married to a monster is what I was married to and didn’t know it.

Anne Anderson: And didn’t know it.

Dianna Coe: I think if he would — if he wouldn’t have married me, she’d still be alive.

Allison Edwards Brocato

But in the wake of the trial, it was time to turn away from Foreman and remember Catherine Edwards as she was and in her own words.

Det. Tina Lewallen: Wow, I didn’t realize the timing on this one. December the 11th 1994. She was murdered a month later. (Reading from Catherine’s journal): “I have given my life to God and I will follow his path for me. That gives me a feeling of great relief and peace.

Det. Tina Lewallen (reading from Catherine’s journal): “The human spirit is stronger than anything that can happen to it.”

The vibrant beloved schoolteacher in her prime, gone far too soon.

Natalie Morales: If you could talk directly with Mary Catherine Edwards, what would you wish to tell her?

Shera LaPoint: Oh my gosh. (crying) Um, I think I would say I love her and I’m sorry. I’m so sorry this happened to her. … And, um, I was honored to be given the privilege to help give answers, very honored, very honored. She was a very special person. She really was.

Heleniah Adams: Unfortunately, it introduced me to real loss — to trauma, to fear, to grief, to heartbreak. To all the feelings.

Heleniah Adams: A podcast I watched, they — they would always ask aspiring lawyers, “when did you fall in love with law?” And I think that’s when I fell in love with law, in the second grade, when Clayton Foreman took my light from me.

Adams is a student once again. She is studying for her master’s in criminal justice and plans to apply to law school — a tribute to her teacher.

Clayton Foreman is eligible for parole in 2061. By then, he will be 101 years old.

Produced by Mary Murphy. Jenna Jackson is the development producer. Doreen Schechter is the producer-editor. Shaheen Tokhi is the field producer. George Baluzy, Grayce Arlotta-Berner and Chris Crater are the editors. Patti Aronofsky is the senior producer. Nancy Kramer is the executive story editor. Judy Tygard is the executive producer.

CBS News

2 killed in U.S. Civil Air Patrol plane crash near Palisade Mountain in Northern Colorado

Two people were killed and a third was injured when a U.S. Civil Air Patrol plane crashed in Colorado’s Front Range Saturday morning.

The small passenger plane with three people aboard crashed near Storm Mountain and Palisade Mountain west of Loveland around 11:15 a.m., according to the Larimer County Sheriff’s Office. The plane belonged to the Civil Air Patrol, the civilian auxiliary wing of the U.S. Air Force, and was on a routine aerial photography training mission when it went down, officials said.

Pilot Susan Wolber and aerial photographer Jay Rhoten were identified by CAP as those killed and co-pilot Randall Settergren was identified as the person injured. Settergren was airlifted to an area hospital by a National Guard helicopter, where he is undergoing medical care.

CBS

“The volunteers of Civil Air Patrol are a valuable part of the Department of Military and Veterans Affairs, and the lifesaving work they do on a daily basis directly contributes to the public safety of Coloradans throughout the state,” Maj. Gen. Laura Clellan, adjutant general of the Colorado Department of Military and Veterans Affairs, said in a statement Saturday.

“We are devastated to hear of the loss of Susan Wolber and Jay Rhoten, and the injury of Randall Settergren, during a training mission in Larimer County. Our thoughts and deepest condolences are with the families of those involved in the crash,” Clellan continued. “I would also like to thank all of the first responders who assisted with rescue efforts.”

Palisade Mountain is in Larimer County, about 20 miles west of Loveland and about 65 miles northwest of Denver. The area is part of the burn scar of the Alexander Mountain Fire, which burned almost 10,000 acres in over two weeks this past summer.

The crash happened about 200 feet below the summit of Palisade Mountain in an area that includes tall trees and steep hills as part of the mountain range. Rescue crews were heard on radio traffic working to find a landing zone for rescue helicopters. No structures were impacted by the crash.

The plane crashed in “very rugged” and “extensive and rocky terrain,” Ali Adams, a Larimer County Sheriff’s Office spokeswoman, said at a news conference. First responders had to hike out to the site and the sole survivor was “severely injured” when responders finally got to them.

Rescue efforts were ongoing at 3:15 p.m., according to Adams, and recovery efforts for the two deceased people’s bodies could take several days.

Several agencies responded, including the Loveland Fire Rescue Authority, Thompson Valley EMS and the National Guard.

The Larimer County Sheriff’s Office is the lead agency investigating the crash and the Federal Aviation Administration and National Transportation Safety Board will assist, according to Adams. The NTSB said it too was investigating the crash and identified the plane as a Cessna 182.

“This is one of those incidents that is really low frequency; it doesn’t happen really often, but unfortunately, our first responders have had more than their fair share of responses,” Adams said.

George Solheim lives in the area of the crash. He described conditions as “extremely windy” on Saturday and heard the plane just prior to the crash. He says he could hear “loud ‘throttle up/down’ immediately prior to sudden silence at (the) time of (the) crash. Couldn’t hear sounds of impact from here.”

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis extended his sympathy to the families of the victims in a statement Saturday evening:

“I’m saddened to hear of the loss of two dedicated Civil Air Patrol members, Pilot Susan Wolber and aerial photographer Jay Rhoten, who lost their lives in today’s crash and my thoughts are with their families, friends and colleagues. These individuals, along with survivor co-pilot Randall Settergren, who was injured, served the Civil Air Patrol as volunteers who wanted to help make Colorado a better, safer place for all. The State of Colorado is grateful for their commitment to service and it will not be forgotten. I also want to thank the first responders who assisted with the rescue and recovery efforts.”

CBS News

Fred Harris, former Democratic U.S. senator and presidential candidate, dies at 94

Fred Harris, a former U.S. senator from Oklahoma, presidential hopeful and populist who championed Democratic Party reforms in the turbulent 1960s, died Saturday. He was 94.

Harris’ wife, Margaret Elliston, confirmed his death to The Associated Press. He had lived in New Mexico since 1976.

“Fred Harris passed peacefully early this morning of natural causes. He was 94. He was a wonderful and beloved man. His memory is a blessing,” Elliston said in a text message.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Harris served eight years in the Senate, first winning in 1964 to fill a vacancy, and made unsuccessful bid for the presidency in 1976.

“I am deeply saddened to learn of the passing of my longtime friend Fred Harris today,” Democratic New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham wrote in a post to social media. “Harris was a towering presence in politics and in academia, and his work over many decades improved New Mexico and the nation. He will be greatly missed.”

Democratic Sen. Martin Heinrich of New Mexico said in a statement that “New Mexico and our nation have lost a giant,” describing him as a “tireless champion of civil rights, tribal sovereignty and working families.”

It fell to Harris, as chairman of the Democratic National Committee in 1969 and 1970, to help heal the party’s wounds from the tumultuous national convention in 1968 when protesters and police clashed in Chicago.

He ushered in rule changes that led to more women and minorities as convention delegates and in leadership positions.

“I think it’s worked wonderfully,” Harris recalled in 2004, when he was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in Boston. “It’s made the selection much more legitimate and democratic.”

“The Democratic Party was not democratic, and many of the delegations were pretty much boss-controlled or -dominated. And in the South, there was terrible discrimination against African Americans,” he said.

Harris ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1976, quitting after poor showings in early contests, including a fourth-place win in New Hampshire. The more moderate Jimmy Carter went on to win the presidency.

Harris moved to New Mexico that year and became a political science professor at the University of New Mexico. He wrote and edited more than a dozen books, mostly on politics and Congress. In 1999 he broadened his writings with a mystery set in Depression-era Oklahoma.

Throughout his political career, Harris was a leading liberal voice for civil rights and anti-poverty programs to help minorities and the disadvantaged. Along with his first wife, LaDonna, a Comanche, he also was active in Native American issues.

“I’ve always called myself a populist or progressive,” Harris said in a 1998 interview. “I’m against concentrated power. I don’t like the power of money in politics. I think we ought to have programs for the middle class and working class.”

“Today ‘populism’ is often a dirty word because of how certain leaders wield power,” Heinrich said in his statement Saturday. “But Fred represented a different brand of populism — one that was never mean or exclusionary. Instead, Fred focused his work and attention on regular people who are often overlooked by the political class.”

Harris was a member of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, the so-called Kerner Commission, appointed by then-President Lyndon Johnson to investigate the urban riots of the late 1960s.

The commission’s groundbreaking report in 1968 declared, “our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal.”

Thirty years later, Harris co-wrote a report that concluded the commission’s “prophecy has come to pass.”

“The rich are getting richer, the poor are getting poorer and minorities are suffering disproportionately,” said the report by Harris and Lynn A. Curtis, president of the Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation, which continued the work of the commission.

Norman Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute said Harris rose to prominence in Congress as a “fiery populist.”

“That resonates with people…the notion of the average person against the elite,” Ornstein said. “Fred Harris had a real ability to articulate those concerns, particularly of the downtrodden.”

In 1968, Harris served as co-chairman of the presidential campaign of then-Vice President Hubert Humphrey. He and others pressed Humphrey to use the convention to break with Johnson on the Vietnam War. But Humphrey waited to do so until late in the campaign, and narrowly lost to Republican Richard Nixon.

“That was the worst year of my life, ’68. We had Dr. Martin Luther King killed. We had my Senate seatmate Robert Kennedy killed and then we had this terrible convention,” Harris said in 1996.

“I left the convention — because of the terrible disorders and the way they had been handled and the failure to adopt a new peace platform — really downhearted.”

After assuming the Democratic Party leadership post, Harris appointed commissions that recommended reforms in the procedures for selecting delegates and presidential nominees. While lauding the greater openness and diversity, he said there had been a side effect: “It’s much to the good. But the one result of it is that conventions today are ratifying conventions. So it’s hard to make them interesting.”

“My own thought is they ought to be shortened to a couple of days. But they are still worth having, I think, as a way to adopt a platform, as a kind of pep rally, as a way to get people together in a kind of coalition-building,” he said.

Harris was born Nov. 13, 1930, in a two-room farmhouse near Walters, in southwestern Oklahoma, about 15 miles from the Texas line. The home had no electricity, indoor toilet or running water.

At age 5 he was working on the farm and received 10 cents a day to drive a horse in circles to supply power for a hay bailer.

He worked part-time as a janitor and printer’s assistant to help for his education at University of Oklahoma. He earned a bachelor’s degree in 1952, majoring in political science and history. He received a law degree from the University of Oklahoma in 1954, and then moved to Lawton to practice.

In 1956, he won election to the Oklahoma state Senate and served for eight years. In 1964, he launched his career in national politics in the race to replace Sen. Robert S. Kerr, who died in January 1963.

Harris won the Democratic nomination in a runoff election against J. Howard Edmondson, who left the governorship to fill Kerr’s vacancy until the next election. In the general election, Harris defeated an Oklahoma sports legend — Charles “Bud” Wilkinson, who had coached OU football for 17 years.

Harris won a six-year term in 1966 but left the Senate in 1972 when there were doubts that he, as a left-leaning Democrat, could win reelection.

Harris married his high school sweetheart, LaDonna Vita Crawford, in 1949, and had three children, Kathryn, Byron and Laura. After the couple divorced, Harris married Margaret Elliston in 1983. A complete list of survivors was not immediately available Saturday.

CBS News

Compromise deal reached at COP29 climate talks for $300 billion a year to poor nations

Countries agreed on a deal to inject at least $300 billion annually in humanity’s fight against climate change, aimed at helping poor nations cope with the ravages of global warming at tense United Nations climate talks in the city where industry first tapped oil.

The $300 billion will go to developing countries who need the cash to wean themselves off the coal, oil and gas that causes the globe to overheat, adapt to future warming and pay for the damage caused by climate change’s extreme weather. It’s not near the full amount of $1.3 trillion that developing countries were asking for, but it’s three times the $100 billion a year deal from 2009 that is expiring. Delegations said this deal is headed in the right direction, with hopes that more money flows in the future.

“Everybody is committed to having an agreement,” Fiji delegation chief Biman Prasad said as the deal was being finalized. “They are not necessarily happy about everything, but the bottom line is everybody wants a good agreement.”

It’s also a critical step toward helping countries on the receiving end create more ambitious targets to limit or cut emissions of heat-trapping gases that are due early next year. It’s part of the plan to keep cutting pollution with new targets every five years, which the world agreed to at the U.N. talks in Paris in 2015.

The Paris agreement set the system of regular ratcheting up climate fighting ambition as away to keep warming under 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The world is already at 1.3 degrees Celsius and carbon emissions keep rising.

Countries also anticipate that this deal will send signals that help drive funding from other sources, like multilateral development banks and private sources. That was always part of the discussion at these talks — rich countries didn’t think it was realistic to only rely on public funding sources — but poor countries worried that if the money came in loans instead of grants, it would send them sliding further backward into debt that they already struggle with.

“The $300 billion goal is not enough, but is an important down payment toward a safer, more equitable future,” said World Resources Institute President Ani Dasgupta. “This deal gets us off the starting block. Now the race is on to raise much more climate finance from a range of public and private sources, putting the whole financial system to work behind developing countries’ transitions.”

It’s more than the $250 billion that was on the table in the first draft of the text, which outraged many countries and led to a period of frustration and stalling over the final hours of the summit. After an initial proposal of $250 billion a year was soundly rejected, the Azerbaijan presidency brewed up a new rough draft of $300 billion, that was never formally presented, but also dismissed roundly by African nations and small island states, according to messages relayed from inside.

The several different texts adopted early Sunday morning included a vague but not specific reference to last year’s Global Stocktake approved in Dubai. Last year there was a battle about first-of-its-kind language on getting rid of the oil, coal and natural gas, but instead it called for a transition away from fossil fuels. The latest talks only referred to the Dubai deal, but did not explicitly repeat the call for a transition away from fossil fuels.

Countries also agreed on the adoption of Article 6, creating markets to trade carbon pollution rights, an idea that was set up as part of the 2015 Paris Agreement to help nations work together to reduce climate-causing pollution. Part of that was a system of carbon credits, allowing nations to put planet-warming gasses in the air if they offset emissions elsewhere. Supporters said a U.N.-backed market could generate up to an additional $250 billion a year in climate financial aid.

Despite its approval, carbon markets remain a contentious plan because many experts say the new rules adopted don’t prevent misuse, don’t work and give big polluters an excuse to continue spewing emissions.

“What they’ve done essentially is undermine the mandate to try to reach 1.5,” said Tamara Gilbertson, climate justice program coordinator with the Indigenous Environmental Network. Greenpeace’s An Lambrechts, called it a “climate scam” with many loopholes.

With this deal wrapped up as crews dismantle the temporary venue, many have eyes on next year’s climate talks in Belem, Brazil.