CBS News

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin on the strength of a diverse military

Earlier this month, Lloyd Austin, the nation’s first African American secretary of defense, returned to West Point, the institution that forever changed his life. “When I first came to West Point,” he told the corps of cadets, “I had never been north of Georgia.”

He spoke to the nation’s next generation of Army officers about what it means to lead in combat: “Artillery was exploding all around us. The troops in the TOC [Tactical Operations Center] were watching me intently, waiting to hear what I had to say. And at that moment, I realized that they would follow me through fire if they trusted that I knew the way forward.”

CBS News

When the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003, Austin was giving the orders for the lead Army division. “I was calling the shots in terms of where brigades were moving, and so I needed to be right up at the front of the formation,” he said.

He ordered what became known as the “Thunder Run” into the heart of Baghdad. He would return to Iraq for two more tours. That’s how he met then-Vice President Joe Biden, who was the Obama administration’s point man for Iraq. “I would be with him as he visited our troops, but he’d also ask for my thoughts, my opinion,” Austin said.

I asked, “When Joe Biden was elected president, did you expect to become secretary of defense?”

“I did not,” Austin replied. “And matter of fact, that was the furthest thing from my mind.”

But he admits he loves his job.

CBS News

That job consists of non-stop closed-door meetings with senior officials, both in the Pentagon and around the world by teleconference. At one such meeting focused on Ukraine, Austin said, “It’s been very helpful in terms of making sure that everyone is kind of rowing in the same direction.”

There is also constant travel, circling the globe visiting allies and troops.

Despite his high-profile job, he is a reluctant public figure. “It’s my personality,” he said. “I don’t make excuses for that. But I don’t think being a private person is necessarily a bad thing.”

I asked, “Do you think it had anything to do with being a Black officer in a white-dominated institution?”

“It does,” he said.

It got him in trouble when he tried to keep his prostate cancer secret even from the president. At a February 1, 2024 press conference, Austin said, “I should have informed my boss; I did not. That was a mistake.”

This private person nonetheless had to stand up in the Pentagon’s briefing room and talk for an hour about his prostate. He says he is now cancer-free. “I thank God for that,” he said.

His knees have seen a few too many parachute jumps. But back at West Point nearly 50 years after he graduated, he seemed to be basking in the limelight, although he was sharing it with the Army football team having one of its best seasons ever.

At West Point, football is not just a sport; it’s preparation for battle. “They’re just tough and rugged and play together, and that’s what we gotta be,” said coach Jeff Monken, who has turned Army football around. “It’s gotta be teamwork. That’s the lesson they take from this place into the Army.”

“That’s how you’re going to fight,” said Austin. “You’re not going to win a war by yourself.”

Army was undefeated until they ran into Notre Dame, and lost by five touchdowns. Ironically, Notre Dame had been Austin’s first choice to attend: “I’d applied there first, got accepted, got a scholarship, and then I got accepted at West Point,” he recalled. “My father brought me in and said, ‘Hey, you go to Notre Dame, it’s still gonna cost me money. If you go to this school, it’s a great education, and they pay you to go there!'”

“His logic persuaded you,” said Monken.

In high school, Austin’s nickname was “Blade,” courtesy of his school’s football coach. “I was a very thin, kind of wiry young man,” Austin recalled. “I said, ‘Coach, put me in,’ and he said, ‘Son, they’re going to mow you down like a blade of grass.'”

Austin ended up as captain of his high school basketball team in Georgia. He was also one of the people that helped to integrate his school. “I was one of the first students there,” he said, describing the experience as tough.

Over and over, Austin has broken through as the first African American, and has said that he was in situations where he “can’t” fail. “I’ve been in that ‘can’t fail’ position a lot,” he said. “The first African American to be the vice chief of the Army; the first African American to command a division in combat; the first African American to command an entire theater of war.”

He is Exhibit A for anyone who believes the military is a true meritocracy, where you are judged by what you do, not what you look like. But he has been depicted by right-wing firebrands as the leader of a “woke” military which promotes minorities at the expense of war fighting.

In an April 5, 2022 exchange on Capitol Hill, then-Rep. Matt Gaetz, Republican from Florida, made accusations to Austin about leaders being “woke”:

Gaetz: “So while everyone else in the world seems to be developing capabilities and being more strategic, we got time to embrace ‘critical race theory’ at West Point.”

Austin: “The fact that you’re embarrassed by your country, by your military? I’m sorry for that.”

Gaetz: “No, no, no. I’m embarrassed by your leadership. I am not embarrassed for my country. The Biden administration is trying to destroy our military by force-feeding it ‘woke-ism.'”

I asked Austin, “Why is it that that presses your button and all the other criticism just rolls off?”

“I’ve fought alongside these troops,” he replied. “This is a lethal, professional war-fighting machine.”

A machine Austin drove to Baghdad with battlefield daring that critics say has been lost as America became mired in never-ending wars, culminating in the chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Appearing on Fox News in June, Pete Gegseth, Donald Trump’s pick to be the next secretary of defense, said, “Ramming stuff into the Pentagon that has nothing you do with winning wars – what is your gender? What is your race? … The Pentagon likes to say our diversity is our strength. What a bunch of garbage!”

But Austin said he absolutely disagrees with criticism that the drive to include women in all the combat arms has led to a weaker military. “You know, I’ve seen women in combat. I don’t have to guess at this,” he said.

Women were part of his command team during the Iraqi invasion. “I said, ‘If any of you feel that you don’t want to be there at the front of the fight, say so now and I won’t think any less of you.’ One of the women piped up and said, ‘Sir, what are you talking about?’ And what they were telling me was, ‘Quit talking. Let’s get to the fight.'”

One woman eager to get to the fight is First Captain Caroline Robinson, the top cadet in West Point’s Class of 2025. Fifty years ago, when Austin graduated, there were no women here. “And I think because of that, we probably missed a pretty significant part of the population,” he said.

As the top cadet, Robinson can have her pick of any branch in the Army. “So right now, field artillery is my number one branch choice,” she said.

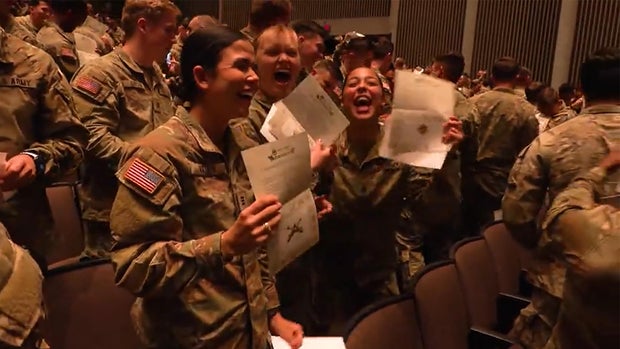

On December 4, “Branch Night,” the cadets of 2025 – one-quarter of them women, and 10 percent African American – found out where they will serve, when they opened envelopes containing their branch assignments.

CBS News

Fifty years ago, there was no such thing as a female artillery officer, or a Black secretary of defense. In response to critics who rail against diversity in the armed forces, Austin told the cadets, “Any military that turns away tough, talented patriots, women or men, is just making itself weaker and smaller. So, enough already!”

For more info:

Story produced by Mary Walsh. Editor: George Pozderec.

CBS News

AI “nudify” sites lack transparency, researcher says

Clothoff, one of the most popular sites using artificial intelligence to generate fake nude photos of real people, uses what are called redirect sites to trick online payment services, according to a researcher.

Millions visit the more than 100 “nudify” sites online each month, according to Graphika, a company that analyzes social networks. And it’s not clear who’s running Clothoff, according to Kolina Koltai, a senior researcher at the international investigative group Bellingcat.

“There is a really inherent shadiness that’s happening,” she said. “They’re not being transparent about who owns it. They’re obviously trying to mask their payments.”

How Clothoff works

Visitors to Clothoff are told that they must be 18 or older to use the website and that they can’t use other’s photos without permission. They’re also told they can’t use pictures of people who are under the age of 18. Clothoff claims on its website that: “processing of minors is impossible.”

“You’ll see, as we click accept, that there’s no verification. And now we’re already here,” Koltai said about entering the website.

Explicit photos are shown right away after clicking accept. Generating a nude photo on Clothoff is free the first time. After that, it costs from $2-$40.

60 Minutes

There’s also a poses feature, which allows people to generate images of people in different sex poses.

Clothoff and other “nudify” sites encourage customers to promote their services online, where users often show off their favorite before and after AI nudes on social media.

Koltai said she’s seen people post AI-generated nude images of what are clearly high school girls on social media. She says she’s done reverse image searches for the original photos.

“And they’re, like, a high school girl’s, like, swim meet. You’ll see these are very clearly, these are minors, and adult content is being made of them nonconsensually, then also being posted on social media,” she said.

Payment methods on “nudify” sites

When 60 Minutes looked at the site with Koltai, we noticed there was a wide variety of payment options available on Clothoff, including PayPal, credit cards and Google Pay.

In many cases, online payment services have policies barring their use for images like the ones generated on “nudify” sites, but the “nudify” sites have workarounds. Koltai found that Clothoff and other sites redirect their customers’ payments through phony websites, pretending to sell things like flowers and photography lessons.

PayPal told 60 Minutes it banned Clothoff from its platform a year ago and shuts down the accounts for these redirect sites when they find them. The problem is Clothoff often just creates new ones.

More deception from “nudify” site

On its website, Clothoff lists a name, Grupo Digital, with an address in Buenos Aires, Argentina, implying that’s where Clothoff is based.

But when 60 Minutes went there, it turned out to be the office of a YouTube channel that covers politics. The employee that answered the door said she’d never heard of Clothoff and that they were not associated with them.

Clothoff also made up a fake CEO, Koltai discovered. She believes his headshot is AI-generated as well.

“You look at the sophistication of these really large sites, it’s completely different than, say, some guy in a basement that set up a site that he’s trying to do it on his own,” Koltai said. “When these sites launched, and the way that they’ve been developing and going this past year, it is not someone’s first rodeo. It’s not the first time they set up a complex network.”

60 Minutes reached out to Clothoff via email, but no one ever responded.

CBS News

Take a look inside Hermès with artistic director Pierre-Alexis Dumas | 60 Minutes

In Greek mythology, Hermes, the son of Zeus was imagined with winged sandals, and a winged hat, symbols of his celebrated speed. Today, the French fashion house Hermès that shares his name is also known for its accessories…elegant scarves, ties and handbags all meticulously made but at a glacial pace. It can take years for monied customers to get their hands on certain Hermès handbags, a process steeped in more mythology than even the Greeks could’ve imagined. The craft and culture behind the brand has been preserved for nearly 200 years, by one family, and is seldom seen by outsiders. But this spring, we were invited to Paris to spend some time behind the silk curtains of the house of Hermès.

On a rainy afternoon, we watched as Pierre-Alexis Dumas, the artistic director of Hermès, turned his discerning eye to dozens of potential scarf designs. Colors and patterns displayed on what looked like the world’s chicest clothesline. Hermès scarves are screened and stitched by hand. Some designs two years in the making. The only part of the process that happens quickly is this. Dumas chose the colors for next season’s scarves in less than an hour.

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: I’m a happy man. Bravo!

Cecile Pesce: Merci! Pierre-Alexis

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: Et voila. Look at the disaster…A mountain of hope reduced to ashes.

60 Minutes

The house of Hermès wasn’t built on silk but rather, saddles. In 1837, Thierry Hermès began selling bespoke harnesses in Paris. That led to luggage, and eventually handbags. More than a century later, Hermès is a more than $200 billion luxury brand with a catalog that includes everything from ready-to-wear to jewelry and furniture. Pierre-Alexis Dumas is the sixth generation of his family to take the reins.

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: I think it’s a wonderful way to enter the store.

He took us through a tunnel of orange boxes into 24 Faubourg in Paris, Hermès flagship and heart for more than a century.

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: My grandfather worked here, and then my father worked here. When I was a child, his office, just on the first floor. Now it’s the jewelry section.

The store is like the Louvre of luxury goods, complete with reminders to look but don’t touch. The brand’s masterpieces include this $48,000 purse and, if you have money left over, this $272,000 pool table.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Do you ever make a decision based on cost? Budget? Like, “This will be less expensive if we do it this way.”

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: I can’t work like that. I’ve always heard that Hermès is very costly. It’s not expensive. It’s costly.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What’s the difference?

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: The cost is the actual price of making an object properly with the required level of attention so that you have an object of quality. Expensive is a product, which is not delivering what it’s supposed to deliver, but you’ve paid quite a large amount of money for it, and then it betrays you. That’s expensive.

60 Minutes

A distinctly French philosophy stitched into the DNA of Hermès. Dumas says the company has never had a marketing department. Its allure, he says, comes from a century of superb craftsmanship and serendipity. Take this trapezoid shaped purse. In 1935, Dumas’ grandfather designed the bag; it wasn’t a hit. But as legend has it, 20 years later, an expecting Grace Kelly used the bag to hide her belly from peering paparazzi. Soon women flooded Hermès, asking for what was eventually renamed the Kelly bag. Hermès scarves have been favored by American royalty and actual royalty for decades. The kind of product placement money can’t buy. Even the brand’s famous citrus-colored boxes, a color the company trademarked in the U.S., was a happy accident of the 1940s.

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: In 1946 there was shortage of everything. And when my great uncle went to see– his supplier of paper, manufacturing boxes. The supplier said, “I’m sorry, we don’t have that beige paper anymore.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Because of the war?

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: Yeah, because of the war and short supplies and he said– “I only have that stock of that roll of orange paper that nobody wants.”

Sharyn Alfonsi: Eyes light up when they see that orange–

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: Serendipity.

And it was serendipity that led to the piece de resistance at Hermès, “the Birkin,” designed in 1984 by Dumas’ father after he was seated next to British actress Jane Birkin on a flight to London.

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: And she told him, “Well, let me tell you, I’m not happy about my bag. I want something more loose with bigger handles, and ease– and– and always open when I carry it.” And as she was talking, my father was very good at sketching.

Sharyn Alfonsi: He sketched it right there in that moment?

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: Yeah. But just an idea. You know? “A bit something like that?” And she said, “Yeah. That would be great.”

It was. Today, the Birkin is the most coveted and costly handbag in the world. A Birkin retails around $9,000 and at auction can fetch upwards of hundreds of thousands of dollars. But here is the surreal twist of Hermès exclusivity, even if you can afford to buy a Birkin bag – chances are you can’t. The stores typically don’t have any to sell. Dumas says Hermès simply can’t keep up with demand.

60 Minutes

Sharyn Alfonsi: If somebody wants the bag, how do they get the bag?

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: Well, you have to walk into an Hermès store, and uh– you have to be patient.

Sharyn Alfonsi: But you know the world we live in, right? You know that if somebody’s– has the funds and they want the bag, they want the bag now.

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: Yes. Um, I have children too. And I have desires too. But I’m saying it’s a long process. You go to a store. You get an appointment. You meet a salesperson. You talk about what you want. It’s not available. You’ll have to wait. They’ll come back to you. It takes a long time. Eventually, it’s gonna happen.

Store managers act as gatekeepers for disciples of the brand. There are stories of years-long waiting lists for bags and waiting lists to get on the waiting list. Along with whispers from Wall Street that the company is brilliantly gaming the customer.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Hermès has been accused of, you know, creating this artificial scarcity to pump up demand. How do you respond to that?

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: It makes me smile that this is– a diabolical– marketing idea that can only come out of people obsessed with marketing. But we don’t have a marketing department at Hermès. So first of all, when I heard that, I was like, “What? Oh. Okay, I get it. Yeah, well, no.” Whatever we have, we put on the shelf, and it goes.

Sharyn Alfonsi: There’s not a room where you guys are holding all the bags back and saying, “Let’s see what happens.”

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: Maybe we should.

The simple truth, Dumas says, is that Hermès doesn’t have enough artisans to build the bags, which for a century he says have been made from start to finish by a single craftsman.

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: So I always like to say that Hermès is an old lady with startup issues, cause we’ve grown so fast in such a per– a small period. How can you grow so fast without changing what makes you strong?

Sharyn Alfonsi: How can you grow so fast without changing your values?

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: By training people. Training a lot of people. For a profession which will be a life profession. They will finish their career at Hermès.

60 Minutes

In 2021, the house opened a training center in leatherwork where 400 graduates a year are schooled in the art of “savoir-faire” or know-how of making things by hand. That includes mastering Hermès’ signature “saddle stitch.”

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: When you have a carriage which is pulled by five horses you better– make sure that all the equipment you’re using is going to be strong. So saddle stitching techniques were not about trying to be hidden. They were about being strong and functional.

Today, it is a hallmark of the Hermès bags.

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: And here is a stitch.

Dumas learned to saddle stitch as a boy, upstairs at the Faubourg, in the workshop where they still build saddles today. He thought it was the perfect place for a lesson.

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: You’re gonna hold by applying a gentle pressure with your legs.

Sharyn Alfonsi: With my thighs.

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: Yes, with your thighs. You’re gonna be able to hold it– that little piece of leather so that your hands are free to stitch.

Sharyn Alfonsi: OK.

With needles in both hands, you’re supposed to pull a strong linen thread coated in beeswax into precise loops.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So I have to have the hands of a heart surgeon and the thighs of a professional wrestler, right?

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: That’s a very extreme, but, yes, if you manage to do that– you got a job.

60 Minutes

Hermès says the criss-cross of needles that make the knot can’t be replicated by a machine and can take years to master. But those who do, are typically offered positions at one of 23 leather workshops that Hermès has built in villages and towns all over France. This is one of them, in Tournes, a three-hour drive from Paris in the French countryside. The workshop is quiet. There is no jamming of sewing machines, just artisans performing a silent dance with dueling needles. The morning we visited, we met Amandine and watched as she put the finishing touches on a Kelly, the most difficult bag to build. It starts with 30 distinct cuts of leather and can take 20 hours to complete, four hours for just the handle. There are no manuals or cheat sheets, artisans rely on their training and muscle memory to make every bag.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Which bags do you know how to make?

Amandine: Le Kelly, le Birkin, le Lindy, uh le Jypsiere, le Shoulder.

Sharyn Alfonsi: That you’ve memorized.

She told us she started making bags at Hermès 15 years ago and went through two years of training.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So you’re able to talk to me and do a saddle stitch at the same time.

Amandine: Oui. C’est possible.

No one seems to be rushing at the workshop. The pace is leisurely. No looming clocks or quotas. Just the slow pursuit of perfection. And when the bag is completed…

60 Minutes

Sharyn Alfonsi: Do you have a special stamp you put in the bag?

Amandine (speaking French): “Yes, we do sign our bags.”

Yes, we do…she said, but it’s a secret. A secret because that hidden mark of the artisan …is how Hermès bags are authenticated. By creating their own pipeline of craftsman, Hermès says they have been able to produce more of their coveted handbags than ever. Although, they won’t disclose the exact number. That too is a secret. This year, some customers were so exasperated by all the mystery and their years-long odyssey to secure a Birkin, they’ve sued Hermès.

Pierre-Alexis Dumas says building something timeless takes time. He urged patience, while nearly losing it with us.

Sharyn Alfonsi: If I I went to the Mercedes dealership and I said, “I would like that car. And they said, “OK, you’re gonna have to wait five years,” they’d be out of business.

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: But you’re talking about industrial production. You’re applying your thinking structure of industrial production to craft. We’re about craft. We’re not machines. And we are not compromising on the quality of the way we make the bags. So if the craftsperson is not at the level, his or her bag would not go into the store.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Even if they’ve invested that 20 or 30 hours making it?

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: Yeah.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And there’s no way of speeding it up and keeping quality–

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: Well, speed is the structuring value of the 20th century. We went from horse carriages to the internet. Are we going to be so obsessed with speed and immediate satisfaction? Maybe not? Maybe there is another form of relation to the world, which is linked to patience. To taking the time of making things right. You cannot compress time, at one point, without compromising on quality.

Produced by Michael Karzis. Associate producer, Katie Kerbstat. Broadcast associate, Erin DuCharme. Edited by Matthew Lev.

CBS News

Hermès artistic director Pierre-Alexis Dumas on why a Birkin bag is “costly” rather than “expensive”

Birkin bags, which retail for around $9,000 and can fetch upwards of hundreds of thousands at auction, are not expensive, Hermès artistic director Pierre-Alexis Dumas said.

He instead uses the word “costly” to describe the coveted handbags — and he sees a difference between costly and expensive purchases.

Cost is the price of making a quality luxury bag properly, even if it leaves customers waiting years for a chance to own one. Expensive objects, on the other hand, fail to deliver what customers want. The difference between the two is why clients need to be patient, Dumas says.

“We’re about craft, we’re not machines,” he said. “And we are not compromising on the quality of the way we make the bags.”

The challenge of getting a Birkin bag

The surreal twist of Hermès’ exclusivity is that even customers who can afford one will find it hard to buy a bag. Stores typically don’t have any to sell and the Birkin is not available to purchase on the Hermès website.

“It’s a long process,” Dumas said. “You go to a store, you get an appointment, you meet a salesperson, you talk about what you want. It’s not available. You’ll have to wait. They’ll come back to you. It takes a long time. Eventually, it’s going to happen.”

60 Minutes

Store managers act as gatekeepers. There are stories of years-long waiting lists for bags and waiting lists to get on the waiting list. There are also whispers from Wall Street that the company is brilliantly gaming customers by artificially creating scarcity.

Dumas said that’s the kind of marketing idea that can only come from people obsessed with marketing and Hermès, he said, doesn’t have a marketing team.

“Whatever we have, we put on the shelf, and it goes,” he said.

Handcrafting in a high-speed world

Hermès doesn’t have enough artisans to build the bags, which for a century have been made from start to finish by a single craftsman.

“I always like to say that Hermès is an old lady with startup issues, because we’ve grown so fast in such a small period,” Dumas said. “How can you grow so fast without changing what makes you strong?”

The company has turned to training people for life-long careers at Hermès. By creating their own pipeline of artisans, Hermès says it’s been able to produce more of their coveted handbags than ever, though the company won’t disclose an exact number.

The house opened a leatherwork training center in 2021 where 400 graduates a year are schooled in leatherwork, including the brand’s signature saddle stitch, designed to be strong and functional.

With a needle in each hand, the artisan pulls a strong linen thread coated in beeswax into precise loops. The criss-cross of the needles that make the knot can’t be replicated by a machine and can take years to master, according to Hermès.

60 Minutes

The Kelly, the most difficult bag to build, starts with 30 distinct cuts of leather and can take 20 hours to complete –four hours for just the handle. There are no manuals or cheat sheets; artisans rely on their training and muscle memory to make every bag.

Those who do master the needed skills are typically offered positions at one of 23 leather workshops that Hermès has built in villages and towns all over France.

One of them is in Tournes, a three-hour drive from Paris in the French countryside.

The workshop is quiet, without the sound of sewing machines. Inside artisans perform a silent dance with dueling needles. No one at the workshop seems to be rushing. The pace seems leisurely, with no looming clocks or quotas — just the slow pursuit of perfection. Bags are “signed” by the artisans when they’re completed. The hidden mark of the artisan is how Hermès bags are authenticated.

Dumas said building something timeless takes time.

“Speed is the structuring value of the 20th century,” he said. “We went from horse carriages to the internet. Are we going to be so obsessed with speed and immediate satisfaction? Maybe not? Maybe there is another form of relation to the world, which is linked to patience, to taking the time to make things right. You cannot compress time, at one point, without compromising on quality.”

A tradition of quality helped along by serendipity

It’s not just bags made meticulously at a glacial place. Hermès silk scarves are screened and stitched by hand. Some designs are two years in the making.

The craft and culture behind the brand has been preserved by one family for nearly 200 years. The house of Hermès was built on saddles, not silk. In 1837, Thierry Hermès started selling bespoke harnesses in Paris. That led to luggage and, eventually, handbags. More than a century later, Hermès is a more than $200 billion luxury brand with a catalog that includes everything from ready-to-wear clothes to jewelry, furniture and even a $272,000 pool table.

Dumas is the sixth generation of the family to take the reins. His father and grandfather worked at 24 Faubourg in Paris, the Hermès flagship store for more than a century. As a boy, he learned to saddle stitch — the hallmark of Hermès bags — in the Faubourg workshop. Saddles are still built in the workshop today.

The allure of Hermès, Dumas said, comes from a century of superb craftsmanship and happy chance.

One serendipitous success is the brand’s Kelly bag, designed by Dumas’ grandfather in 1935. It wasn’t a hit, but as legend had it, 20 years later an expecting Grace Kelly used the bag to hide her stomach from paparazzi. Women soon flooded Hermès, asking for the bag.

The company’s scarves have been favored by royalty and celebrities for decades, providing the kind of product placement money can’t buy.

60 Minutes

Even the brand’s famous boxes, with their citrus-like color the company trademarked in the U.S., was a happy accident of the 1940s. It was 1946 and there were still World War II shortages. The supplier of papers and manufacturing boxes was out of the beige paper they regularly used.

“And he said, ‘I only have that stock of that roll of orange paper that nobody wants,” Dumas said.

That color ended up being a key part of the brand’s identity.

It was also serendipity that led to the piece de resistance at Hermès, the Birkin. The bag was designed in 1984 by Dumas’ father after he was seated next to British actress Jane Birkin on a flight to London.

“She told him, ‘Well, let me tell you, I’m not happy about my bag. I want something more loose with bigger handles, and ease, and always open when I carry it,'” Dumas said. “And as she was talking, my father was very good at sketching.”

Dumas’ father showed Birkin the sketch and that was that.