CBS News

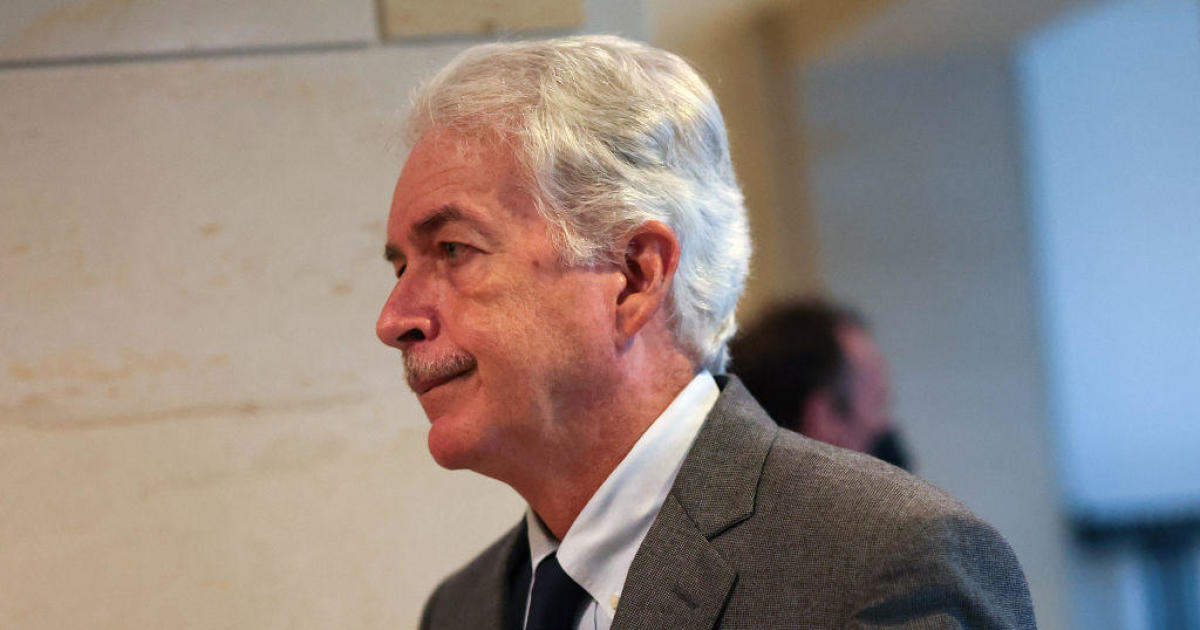

CIA Director William Burns to travel to Europe for fourth round of Gaza hostage talks

CIA Director William Burns will soon travel to Europe for a fourth round of multiparty talks aimed at brokering a broadened deal to release the more than 100 hostages still being held in Gaza, a source familiar with the matter confirmed to CBS News on Thursday.

Burns is expected to meet in France with David Barnea, the head of Israel’s Mossad intelligence agency, and Qatari Prime Minister Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani, the source said. Egyptian intelligence chief Abbas Kamel is also involved. All four have engaged in previous rounds of negotiations aimed at freeing hostages in exchange for a cessation of hostilities, a principal demand by Hamas.

Six male U.S. citizens are believed to be among those still being held hostage in Gaza. Hamas took hundreds of people hostage during its attacks across Israel on Oct. 7.

The CIA declined to comment on Burns’ travel schedule, which is classified. The director traveled to Doha twice in November and to Warsaw in December as part of an effort to secure the release of the remaining hostages.

The latest talks follow meetings this month between the National Security Council’s Middle East coordinator Brett McGurk and senior Egyptian and Qatari officials, part of a diplomatic push by Washington and Doha to get Israel and Hamas to negotiate a deal. The effort coincides with a Biden administration push for Israel to wind down its intense military operations in Gaza.

The family members of the six remaining Israeli-American hostages also met with several Biden advisers on Jan. 18 in Washington. In a statement marking 100 days of the Israel-Hamas war, President Biden said the U.S. “will never stop working to bring Americans home.”

On Sunday, as news broke of McGurk’s latest diplomatic push, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu released a scathing statement saying that Israel rejected Hamas’ terms for a release because they included an end to the war.

“Hamas is demanding, in exchange for the release of our hostages, the end of the war, the withdrawal of our forces from Gaza, the release of the murderers and rapists of the Nukhba and leaving Hamas in place,” he said. “I am not prepared to accept such a mortal blow to the security of Israel; therefore, we will not agree to this.”

Netanyahu’s government has faced domestic political pressure from the hostages’ families, who continue to campaign for the release of their loved ones as Israel’s military campaign continues in the 25-mile-long Palestinian enclave.

Netanyahu’s public position has been that military force will ultimately get Hamas to capitulate and agree to release the hostages. However, a divide within the war cabinet recently spilled out into public when Gadi Eisenkot, a former general, told an Israeli TV outlet that it would be impossible to secure the safe return of the hostages without a diplomatic agreement.

A source familiar with the negotiations over the hostages said Netanyahu’s opposition was an impediment to reaching an agreement. The Israeli embassy did not have immediate comment.

The attempts to broker a diplomatic deal have been at an impasse since an initial breakthrough in November led by the U.S. and Qatar that resulted in the release of more than 100 hostages and more than 200 Palestinian prisoners.

Tensions between Israel and Qatar were recently heightened after leaked audio surfaced of Netanyahu talking down Doha’s efforts while in conversation with Israeli hostage families.

CBS News

A lowrider artist’s journey “out of the darkness”

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

How Kenya became the “Silicon Savannah”

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

Kenyan workers with AI jobs thought they had tickets to the future until the grim reality set in

Being overworked, underpaid, and ill-treated is not what Kenyan workers had in mind when they were lured by U.S. companies with jobs in AI.

Kenyan civil rights activist Nerima Wako-Ojiwa said the workers’ desperation, in a country with high unemployment, led to a culture of exploitation with unfair wages and no job security.

“It’s terrible to see just how many American companies are just doing wrong here,” Wako-Ojiwa said. “And it’s something that they wouldn’t do at home, so why do it here?”

Why tech giants come to Kenya

The familiar narrative is that artificial intelligence will take away human jobs, but right now it’s also creating jobs. There’s a growing global workforce of millions toiling to make AI run smoothly. It’s gruntwork that needs to be done accurately and fast. To do it cheaply, the work is often farmed out to developing countries like Kenya.

Nairobi, Kenya, is one of the main hubs for this kind of work. It’s a country desperate for work. The unemployment rate is as high as 67% among young people.

“The workforce is so large and desperate that they could pay whatever and have whatever working conditions, and they will have someone who will pick up that job,” Wako-Ojiwa said.

60 Minutes

Every year, a million young people enter the job market, so the government has been courting tech giants like Microsoft, Google, Apple and Intel. Officials have promoted Kenya as a “Silicon Savannah” — tech savvy and digitally connected.

Kenyan President William Ruto has offered financial incentives on top of already lax labor laws to attract the tech companies.

What “humans in the loop” do with AI

Naftali Wambalo, a father of two with a college degree in mathematics, was elated to find work in Nairobi in the emerging field of artificial intelligence. He is what’s known as a “human in the loop”: someone sorting, labeling and sifting through reams of data to train and improve AI for companies like Meta, OpenAI, Microsoft and Google.

Wambalo and other digital workers spent eight hours a day in front of a screen studying photos and videos, drawing boxes around objects and labeling them, teaching AI algorithms to recognize them.

Human labelers tag cars and pedestrians to teach autonomous vehicles not to hit them. Humans circle abnormalities in CTs, MRIs and X-rays to teach AI to recognize diseases. Even as AI gets smarter, humans in the loop will always be needed because there will always be new devices and inventions that’ll need labeling.

Humans in the loop are found not only in Kenya, but also in India, the Philippines and Venezuela. They’re often countries with low wages but large populations — well educated, but unemployed.

Unfair labor practices

What seemed like a ticket to the future was quickly revealed to be anything but for some humans in the loop, who say they’ve been exploited. The jobs offer no stability – some contracts only offer employment for a few days, some weekly and others monthly, Wako-Ojiwa said. She calls the workspaces AI sweatshops with computers instead of sewing machines.

The workers aren’t typically hired directly by the big tech companies – instead, they are employed by mostly American outsourcing companies.

The pay for humans in the loop is $1.50-2 an hour.

“And that is gross, before tax,” Wambalo said.

Wambalo, Nathan Nkunzimana and Fasica Berhane Gebrekidan were employed by SAMA, an American outsourcing company that hired for Meta and OpenAI. SAMA, based in the California Bay Area, employed over 3,000 workers in Kenya. Documents reviewed by 60 Minutes show OpenAI agreed to pay SAMA $12.50 an hour per worker, much more than the $2 the workers actually got, though SAMA says what it paid is a fair wage for the region.

Wambalo disagrees.

“If the big tech companies are going to keep doing this business, they have to do it the right way,” he said. “It’s not because you realize Kenya’s a third-world country, you say, ‘This job I would normally pay $30 in U.S., but because you are Kenya, $2 is enough for you.'”

60 Minutes

Nkunzimana said he took the job because he has a family to feed.

Berhane Gebrekidan lived paycheck to paycheck, unable to save anything. She said she saw people who were fired for complaining.

“We were walking on eggshells,” she said.

They say SAMA pushed workers to complete assignments faster than the companies required, an allegation SAMA denies. If a six-month contract was completed in three months, they could be out of work without any pay for those extra months. They did say Sama would reward them for fast work.

“They used to say ‘thank you.’ They give you a bottle of soda and KFC chicken. Two pieces. And that is it,” Wambalo said.

Ephantus Kanyugi, Joan Kinyua, Joy Minayo, Michael Geoffrey Asia and Duncan Koech all worked for Remotaks, a click-work platform operated by Scale AI — another American AI training company facing criticism in Kenya. Workers signed up online and selected remote work, getting paid per task. They said they sometimes went unpaid.

“When it gets to the day before payday, they close the account and say that you violated a policy,” Kanyugi said.

Employees say they have no recourse or even a way to complain.

The company told 60 Minutes that any work done “in line with our community guidelines was paid out.” In March, as workers started complaining publicly, Remotasks abruptly shut down in Kenya, locking all workers out of their accounts.

The mental toll of AI training

Workers say some of the projects for Meta and OpenAI also caused them mental harm. Wambalo was assigned to train AI to recognize and weed out pornography, hate speech and excessive violence from social media. He had to sift through the worst of the worst content online for hours on end.

“I looked at people being slaughtered,” Wambalo said. “People engaging in sexual activity with animals. People abusing children physically, sexually. People committing suicide.”

Berhane Gebrekidan thought she’d been hired for a translation job, but she said what she ended up doing was reviewing content featuring dismembered bodies and drone attack victims.

60 Minutes

“I find it hard now to even have conversations with people,” she said. “It’s just that I find it easier to cry than to speak.”

Wambalo said the material he had to review online has hurt his marriage.

“After countlessly seeing those sexual activities, pornography on the job, that I was doing, I hate sex,” he said.

SAMA says mental health counseling was provided by “fully-licensed professionals.” Workers say it was woefully inadequate.

“We want psychiatrists,” Wambalo said. “We want psychologists, qualified, who know exactly what we are going through and how they can help us to cope.”

Workers fight back

Wambalo and Berhane Gebrekidan are among around 200 digital workers suing SAMA and Meta over “unreasonable working conditions” that caused them psychological problems.

“It was proven by a psychiatrist that we are thoroughly sick,” Nathan Nkunzimana said “We have gone through a psychiatric evaluation just a few months ago and it was proven that we are all sick, thoroughly sick.”

Wambalo said it’s the responsibility of the big tech companies to know how the jobs are impacting workers.

“They are the ones providing the work,” he said.

Berhane Gebrekidan feels the companies know the people they employ are struggling, but they don’t care.

“…Just because we’re Black, or just because we’re just vulnerable for now, that doesn’t give them the right to just exploit us like this,” she said.

Kenya does have labor laws, but they are outdated and don’t touch on digital labor, Wako-Ojiwa, the civil rights activist, said.

“I do think that our labor laws need to recognize it, but not just in Kenya alone,” Wako-Ojiwa said. “Because what happens is when we start to push back, in terms of protections of workers, a lot of these companies…they shut down and they move to a neighboring country.”

SAMA has terminated the harmful content projects Wambalo and Berhane Gebrekidan were working on. The company would not agree to an on-camera interview and neither would Scale AI, which operated the Remotasks website in Kenya.

Meta and OpenAi told 60 Minutes they’re committed to safe working conditions, including fair wages and access to mental health counseling.