CBS News

Can AI help fill the therapist shortage? Mental health apps show promise and pitfalls

Providers of mental health services are turning to AI-powered chatbots designed to help fill the gaps amid a shortage of therapists and growing demand from patients.

But not all chatbots are equal: some can offer helpful advice while others can be ineffective, or even potentially harmful. Woebot Health uses AI to power its mental health chatbot, called Woebot. The challenge is to protect people from harmful advice while safely harnessing the power of artificial intelligence.

Woebot founder Alison Darcy sees her chatbot as a tool that could help people when therapists are unavailable. Therapists can be hard to reach during panic attacks at 2 a.m. or when someone is struggling to get out of bed in the morning, Darcy said.

But phones are right there. “We have to modernize psychotherapy,” she says.

Darcy says most people who need help aren’t getting it, with stigma, insurance, cost and wait lists keeping many from mental health services. And the problem has gotten worse since the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It’s not about how can we get people in the clinic?” Darcy said. “It’s how can we actually get some of these tools out of the clinic and into the hands of people?”

How AI-powered chatbots work to support therapy

Woebot acts as a kind of pocket therapist. It uses a chat function to help manage problems such as depression, anxiety, addiction and loneliness.

The app is trained on large amounts of specialized data to help it understand words, phrases and emojis associated with dysfunctional thoughts. Woebot challenges that thinking, in part mimicking a type of in-person talk therapy called cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT.

60 Minutes

Woebot Health reports 1.5 million people have used the app since it went live in 2017. Right now, users can only use the app with an employer benefit plan or access from a health care professional. At Virtua Health, a nonprofit healthcare company in New Jersey, patients can use it free of charge.

Dr. Jon LaPook, chief medical correspondent for CBS News, downloaded Woebot and used a unique access code provided by the company. Then, he tried out the app, posing as someone dealing with depression. After several prompts, Woebot wanted to dig deeper into why he was so sad. Dr. LaPook came up with a scenario, telling Woebot he feared the day his child would leave home.

He answered one prompt by writing: “I can’t do anything about it now. I guess I’ll just jump that bridge when I come to it,” purposefully using “jump that bridge” instead of “cross that bridge.”

Based on Dr. LaPook’s language choice, Woebot detected something might be seriously wrong and offered him the option to see specialized helplines.

Saying only “jump that bridge” and not combining it with “I can’t do anything about it now” did not trigger a response to consider getting further help. Like a human therapist, Woebot is not foolproof, and should not be counted on to detect whether someone might be suicidal.

Computer scientist Lance Eliot, who writes about artificial intelligence and mental health, said AI has the ability to pick up on nuances of conversation.

“[It’s] able to in a sense mathematically and computationally figure out the nature of words and how words associate with each other. So what it does is it draws upon a vast array of data,” Eliot said. “And then it responds to you based on prompts or in some way that you instruct or ask questions of the system.”

60 Minutes

To do its job, the system must go somewhere to come up with appropriate responses. Systems like Woebot, which use rules-based AI, are usually closed. They’re programmed to respond only with information stored in their own databases.

Woebot’s team of staff psychologists, medical doctors, and computer scientists construct and refine a database of research from medical literature, user experience, and other sources. Writers build questions and answers, which they revise in weekly remote video sessions. Woebot’s programmers engineer those conversations into code.

With generative AI, the system can generate original responses based on information from the internet. Generative AI is less predictable.

Pitfalls of AI mental health chatbots

The National Eating Disorders Association’s AI-powered chatbot, Tessa, was taken down after it provided potentially harmful advice to people seeking help.

Ellen Fitzsimmons-Craft, a psychologist specializing in eating disorders at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, helped lead the team that developed Tessa, a chatbot designed to help prevent eating disorders.

She said what she helped develop was a closed system, without the possibility of advice from the chatbot that the programmers had not anticipated. But that’s not what happened when Sharon Maxwell tried it out.

Maxwell, who had been in treatment for an eating disorder and now advocates for others, asked Tessa how it helps people with eating disorders. Tessa started out well, saying it could share coping skills and get people needed resources.

But as Maxwell persisted, Tessa started to give her advice that ran counter to usual guidance for someone with an eating disorder. For example, among other things, it suggested lowering calorie intake and using tools like a skinfold caliper to measure body composition.

“The general public might look at it and think that’s normal tips. Like, don’t eat as much sugar. Or eat whole foods, things like that,” Maxwell said. “But to someone with an eating disorder, that’s a quick spiral into a lot more disordered behaviors and can be really damaging.”

60 Minutes

She reported her experience to the National Eating Disorders Association, which featured Tessa on its website at the time. Shortly after, it took Tessa down.

Fitzsimmons-Craft said the problem with Tessa began after Cass, the tech company she had partnered with, took over the programming. She says Cass explained the harmful messages appeared after people were pushing Tessa’s question-and-answer feature.

“My understanding of what went wrong is that, at some point, and you’d really have to talk to Cass about this, but that there may have been generative AI features that were built into their platform,” Fitzsimmons-Craft said. “And so my best estimation is that these features were added into this program as well.

Cass did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Some rules-based chatbots have their own shortcomings.

“Yeah, they’re predictive,” social worker Monika Ostroff, who runs a nonprofit eating disorders organization, said. “Because if you keep typing in the same thing and it keeps giving you the exact same answer with the exact same language, I mean, who wants to do that?”

Ostroff had been in the early stages of developing her own chatbot when she heard from patients about what happened with Tessa. It made her question using AI for mental health care. She said she’s concerned about losing something fundamental about therapy: being in a room with another person.

“The way people heal is in connection,” she said. Ostroff doesn’t think a computer can do that.

The future of AI’s use in therapy

Unlike therapists, who are licensed in the state where they practice, most mental health apps are largely unregulated.

Ostroff said AI-powered mental health tools, especially chatbots, need to have guardrails. “It can’t be a chatbot that is based in the internet,” Ostroff said.

Even with the potential issues, Fitzsimmons-Craft isn’t turned off to the idea of using AI chatbots for therapy.

“The reality is that 80% of people with these concerns never get access to any kind of help,” Fitzsimmons-Craft said. “And technology offers a solution –not the only solution, but a solution.”

CBS News

Kansas City Chiefs bring football and romance to Hallmark Channel with new movie

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

Personal bankruptcies are on the rise. When does it make sense to file?

No one wants to file for bankruptcy, but if you’re heading in that direction, delaying the inevitable may only make things worse.

Bankruptcies are still significantly below pre-pandemic levels, but have gone up relative to last year. Personal bankruptcies were up 16% in October from a year ago, as more Americans are seeking debt relief. But those struggling to stay financially afloat should consider the option sooner rather than later, advise experts who study when and why people file.

“When a consumer feels financial pressure, the last thing on their mind is seeking bankruptcy protection,” said Michael Hunter, vice president, business development, at Epiq Aacer, a provider of bankruptcy information and partner to the American Bankruptcy Institute, or ABI. Most people don’t file until 18 to 24 months after they’ve incurred financial hardship, Hunter said.

Researchers, over decades of interviewing thousands of people who’ve declared personal bankruptcy, have found that about two-thirds of individual filers struggle with paying their debts for up to five years before seeking help.

“The common response is people are struggling with their debt for more than two years” before seeking a legal remedy, Robert Lawless, a professor at the University of Illinois College of Law, told CBS MoneyWatch.

“People misunderstand bankruptcy and wait too long to see a bankruptcy lawyer. Most people would benefit by going earlier,” said Lawless, a co-principal investigator in the Consumer Bankruptcy Project, launched in 1981 by a group of academics including Senator Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., a law school professor at the time.

When to file for bankruptcy

Because of the stigma and shame that Americans attach to bankruptcy, people turn to it as a last resort — oftentimes after they have plowed through retirement funds and other assets that would be have been shielded from creditors by filing for debt relief.

“If you are raiding pension or other retirement assets, that is a red flag,” said Lawless, noting those funds are protected from creditors in bankruptcy. Borrowing money to cover current expenses is another warning sign, he offered.

“It makes sense to file if a creditor is going to be able to take away something you need,” said Pamela Foohey, a professor of law at the University of Georgia School of Law in Athens. “If a person is dealing with a wage garnishment that is harming their lives, or if a lender is threatening to repossess your car. If there’s no other way to get a car that will fit your budget, filing could be a way to keep your car, or keep your house.”

Otherwise the broad answer is to first address how they might solve the cause of their financial distress before filing for bankruptcy. “It doesn’t help to find a better-paying job if after bankruptcy more is going out than coming in,” said Lawless.

“If you lost your job, file after you found a new job; if you have a health crisis, you file after you’ve gotten better to discharge all of the medical debt that you’ve racked up,” said Foohey.

If someone undergoes a change in their family situation, whether it’s a divorce or the birth of twins, she advises that they first figure out how they’re going to manage going forward on a budget after the debt is discharged.

“Bankruptcy does one thing, it gets rid of debt. It doesn’t find you a job, it doesn’t put money in your pocket,” said Lawless.

Also, legally speaking, once debt is discharged or a financial repayment plan is approved by a judge, it will be another 5 to 8 years before one can file again.

Chapter 7 versus Chapter 13

It costs about $1,500 to file Chapter 7, and most attorneys require that their fees be paid upfront. Chapter 7 is a liquidation bankruptcy, where one’s nonexempt property and assets — possessions not protected by bankruptcy — are turned over to a trustee, and debt is discharged in 3 to 6 months. According to Lawless, 95% of Chapter 7 don’t have any assets to turn over.

With a Chapter 13, payments can be spread out, however the overall cost is a lot more.

Having to hire and pay an attorney several thousands dollars is also a daunting prospect for those in financial turmoil, but Lawless said a lawyer is a better option than filing for bankruptcy yourself or looking to consumer credit counseling — a service that is typically for-profit and has a long history of problems.

“In Chapter 13, attorneys can allow for nothing upfront, put all their fees in the repayment plan, and on average charge $4,500,” Foohey said.

According to Foohey, only about a third of those who file Chapter 13 make it to the end and have their debts discharged. “Not everyone wants the discharge, but to reset their relationship with their mortgage holder,” she said.

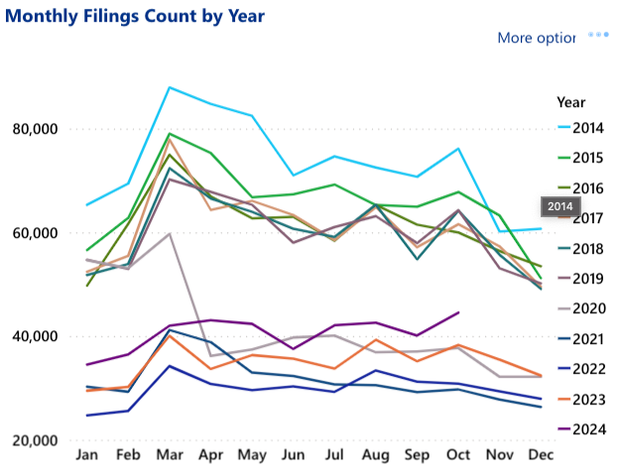

Epiq AACER

A Chapter 13 involves committing to a 3- to 5-year repayment plan. However, many filers that enter the agreements don’t complete them, Lawless relayed. “Homeowners will file 13 so they don’t lose their home. It’s among the tools used to get caught up on mortgage payments,” he said.

Attorneys charge far less for Chapter 7, as it’s a less-complicated process than a Chapter 13. The latter is used for, but a bad idea, to pay for one’s bankruptcy.

“In 7, you have to pay for your bankruptcy upfront. In Chapter 13 you pay your attorney in that 3- to 5-year plan,” said Lawless. “If you’re using 13 to pay your attorney feels that is generally the wrong choice.”

In Lawless’ view, “the No. 1 thing Congress should do is make it possible to pay your Chapter 7 attorney over time, so we don’t have people filing Chapter 13 when they don’t need to.”

Return to pre-COVID numbers

Personal bankruptcy filings averaged about 750,000 a year before COVID-19, but dropped off a cliff during the pandemic, thanks to government aid.

“It was very consistent from 2014 to 2019 — pretty flat, and then the pandemic hit. A lot of us thought volumes would surge,” said Michael Hunter, vice president, business development, at Epiq Aacer. But there was forbearance for student loans, cars and mortgages, he noted.

“Banks were extending olive branches, and we saw bankruptcies plummet to less than half of pre-pandemic levels,” he said.

“There was a lot of money sloshing around,” said Lawless, citing government stimulus programs and other aid. “People paid down their debt,” he stated.

Now, with those financial lifelines largely unplugged, U.S. households are tacking more debt onto household balance sheets. “The biggest surprise is bankruptcy filings haven’t gone up even more,” said Lawless, who expects a return to pre-COVID levels.

Nonbusiness bankruptcy filings fell to under 400,000 before edging back up to 434,000 in 2023, according to statistics published by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. With two months left in 2024, personal bankruptcy filings stood at 405,132 at the end of October.

“We’re still pretty far away from the filing numbers of 2019,” said Foohey. “There was a drastic drop at the time of the pandemic that continued for several years, which is now returning to pre-pandemic levels.”

CBS News

Business pioneers of the Pacific Northwest

Presented by Visit Seattle & CBS News Brand Studio.

There are no shortage of reasons to visit Seattle. Whether you’re drawn to iconic landmarks like the Space Needle, stunning landscapes including Mount Rainier or the innovation-driven economy that keeps the city buzzing, there’s something for everyone. In Seattle, businesses that started here thrive, and that’s reflected in the stories of three of the city’s homegrown brands: Nordstrom, Alaska Airlines and REI.

Nordstrom’s legacy of innovation

Seattle is a magnet for pioneering companies that embody a unique blend of ambition and community. From global corporations like Starbucks, Amazon and Expedia, to beloved local brands, innovation is at the heart of the city’s DNA.

Nordstrom CEO Erik Nordstrom and his family have led one of Seattle’s most iconic brands for over a century.

“My great-grandfather ended up opening up a shoe store that over 123 years has become what our company is today,” he said. “We’ve benefited from everything that the city has become.”

Nordstrom was co-founded in 1901 by Swedish immigrant John Nordstrom. The company has grown into a retail juggernaut with more than 360 locations nationwide. Today, their flagship store remains proudly rooted downtown, just blocks away from their original location.

The business has benefited from how Seattle has evolved over the last century. Nordstrom credits the city’s flourishing technology industry with helping the company keep up with trends.

“We were very early in the e-commerce business, and that was a direct result of having that level of talent here in the city,” he said.

Nordstrom’s story illustrates how Seattle’s forward-thinking culture fuels long-term success.

“Seattle is a no-nonsense hard-working place,” Nordstrom added. “It’s also a very friendly place. And our focus on customer service is something that I think is a reflection of the community here.”

Globally connected with Alaska Airlines

Alaska Airlines takes Seattle’s spirit of adventure to the skies.

The company’s roots go back to 1932 when Mac McGee shuttled customers across the Alaska territory with a single three-seater Stinson plane. More than 70 years ago, the company moved its headquarters to Seattle to take advantage of all the city offers. Alaska Airlines has expanded to over 100 non-stop destinations and connects passengers with over 30 global carriers.

“As Seattle has grown, so have we,” said Constance von Muehlen, Alaska Airlines COO. “I think Seattle is really a gateway to the world and has become more so in the last 20 years.”

The airline’s deep ties to the region also extend to the in-flight experience, where Seattle’s local brands are put on display.

“We offer things like Beecher’s cheese or Evergreens salads or Seattle Chocolate. It’s really a wonderful partnership to showcase the great things that come from this city.”

The great outdoors, the REI way

Seattle is a gateway to adventure, so it’s no surprise the city’s rugged surroundings gave rise to REI. Founders Mary and Lloyd Anderson pooled resources with 21 friends to get better prices on mountain climbing gear in 1938, and Recreational Equipment Incorporated was born.

REI President and CEO Eric Artz credits the region’s natural environment for shaping the brand’s mission.

“The inspiration of REI began with what we have around us here in the Seattle area, which is just the joy of spending time outside in incredible outdoor, natural places,” Artz explained.

With 24 million co-op members and more than 190 locations, REI’s footprint extends far beyond Seattle, yet its core values remain rooted in the Pacific Northwest.

“There is a very entrepreneurial can-do spirit here in the Seattle area. There is a care for one another as well. I think it’s all of those kind of values and attributes that contributed, you know, literally to the idea of the cooperative,“ Artz said.

Collective business ethos is a win for Seattle

Whether it’s Nordstrom’s commitment to service, Alaska Airlines’ adventurous spirit or REI’s passion for stewardship, these businesses demonstrate how Seattle fosters growth and transformation, creating a city where ambition and collaboration shape the future.

Seattle’s hometown companies prove that success extends beyond profit, cultivating a culture of innovation and care that defines the city’s business ecosystem.