CBS News

Students want their colleges to divest from Israel. Here’s what that really means.

College endowments, usually a sleepy part of a university’s operations, are now front and center at the campus protests that are spreading across the nation, with students holding up signs with slogans such as “Disclose! Divest!” and “Divest from death now!”

These demands are central to the student protesters’ efforts, with many of the students condemning what they see as their universities’ financial support of Israel’s war in Gaza. At Brown University, for example, student protesters charge that the school’s $6.6 billion endowment will remain “complicit” until it divests “from Israel and the military-industrial complex.”

The rash of demands on campus for schools to divest from Israel is throwing a spotlight on the little-known world of endowments, while also raising questions about the effectiveness of divestment as a tool to enact concrete change. To be sure, colleges aren’t strangers to calls for divestment, with student protesters in the 1980s demanding their institutions to pull money from companies doing business in apartheid South Africa. More recently, college students have pushed for their universities’ divestment from the fossil fuel industry.

But divestment often is neither a simple nor a quick process, experts say. Endowments are funded by donors, who often direct their money to be used for specific goals — such as providing scholarships for students from certain states or to fund summer study programs.

For instance, Columbia University, whose campus became a lightning rod in the pro-Palestinian protest movement, has an endowment worth $13.6 billion that is comprised of 6,200 funds.

“An endowment isn’t a monolith. They are typically comprised of many different funds, which each have different goals and purposes,” noted Todd Ely, associate professor at University of Colorado Denver’s School of Public Affairs, who is an expert on endowments. “From the perspective of endowments, the big objective is to preserve and grow the endowment,” which allows the university to fund programs, support faculty and provide student scholarships.

Ely added, “That is why it becomes so challenging — the primary objective of an endowment manager isn’t to respond to political and social pressure.”

What does “divest” mean?

“Divestment” in itself simply describes the action of selling or disposing of an investment or asset. But the term has taken on another layer of meaning as college students, activists and others have leaned on the strategy as a way to achieve political goals.

For instance, the protesters believe that by eliminating investments in businesses involved in controversial countries or industries colleges can help bring about change, such as ending apartheid, while also ensuring they reflect their students’ views on ethical issues.

The student protesters “don’t want to be part of or have their tuition dollars go to an institution that is profiting from” what they see as immense human rights abuses, noted Kelly Grotke, a founding partner of Pattern Recognition: A Research Collective, who researches and consults with students, alumni groups, faculty and others on divestment and endowments.

What are endowments, and how big are they?

Endowments are funds provided by donors to a university or college that can be earmarked for specific goals, like supporting an endowed chair for a faculty member or providing scholarships for students; or which can be used for unrestricted spending.

Endowment funds exist for perpetuity, with the university typically spending a smaller amount each year than its annual return. In that way, the endowment can continue to grow. For instance, in its most recent fiscal year, Columbia’s endowment spent about 5.2% of its funds, although its trailing 10-year return is 8%.

The current focus on college endowments is coming at a time when universities control more assets than ever before. Roughly 700 college and university endowments manage about $840 billion in assets, according to a recent study from the National Association of College and University Business Officers and the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America-College Retirement Equities Fund.

While not an apples-to-apples comparison, an earlier Government Accountability Office report found that about 1,900 higher-education institutions in 2008 had a combined $400 billion in endowment holdings.

Are college endowments invested in Israel?

It’s unclear because endowments typically don’t disclose their investments; that lack of transparency has become a sticking point for many student protesters.

The calls for colleges to divest from Israel aren’t actually new, but are picking up supporters as the war in Gaza continues. The movement stems from 2005, when some Palestinian groups created an effort called boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) that was joined by some students and academic groups, according to Carleton University political science professor Mira Sucharov in The Conversation.

BDS has focused on divestment, as well as urging consumers to avoid buying goods or services from Israel, she noted.

Part of the difficulty in determining whether an endowment is even invested in Israel, either directly or indirectly, is the changing nature of how colleges invest their funds, Grotke said. Today, a large chunk of endowments are invested in so-called “alternative investments,” which describe strategies outside the typical mom-and-pop style of buying stocks and holding them for the long term.

Alternative investments include hedge funds, private equity firms, venture capital and other vehicles that are typically cloaked in secrecy because their managers don’t want to tip off rivals to their strategies. Typically, investors agree to invest their funds for a period of time, which can stretch for several years, making it impossible to withdraw money.

“There is so much privacy in what is being held, especially in alternative funds,” Grotke said, pointing out that much of Oberlin’s endowment is invested in alternative strategies. “If you are dealing with an index fund, you can go in and see what’s in there. You can’t do that with an alternative fund.”

Are colleges agreeing to divest?

Only one U.S. college, Evergreen State College, has agreed so far to divest. A few others, including Northwestern and Brown University, have said they will disclose their investment exposure to Israel, but even that might not provide much clarity, Grotke noted.

For instance, in the text of its deal with its pro-Palestinian protesters, Northwestern says it will “answer questions from any internal stakeholder about specific holdings, held currently or within the last quarter, to the best of its knowledge and to the extent legally possible.”

“That is language to get around disclosure,” Grotke noted. The agreement “will potentially exclude any divestment because of those contractual relationships” with alternative investment managers.

She added, “Because of the complexity of finance, they will want to look like they will cooperate, but they might not be able to.”

Northwestern didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Does divestment work?

That’s up for debate, experts said.

On the one hand, the push for colleges to divest from the fossil fuel industry has “pushed a lot of new conversations in endowments about how to think about the climate change and carbon risk,” noted Georges Dyer, co-founder and executive director of the Intentional Endowments Network, which works with endowments on strategies such as low-carbon investments.

But, he added, “A big part of the debate is what impact does divestment have.”

Research on previous divestment efforts isn’t encouraging, at least in terms of whether selling assets negatively impacts the countries or companies that are targeted. For instance, one analysis of the anti-apartheid divestment push in the ’80s found that it “had little discernible effect either on the valuation of banks and corporations with South African operations or on the South African financial markets.”

But that may not be the whole point, said Grotke, noting that the anti-apartheid movement succeeded in “raising awareness of human right abuses” in South Africa. With today’s protests, the students are saying they “don’t want to live in a world in which they are implicated in” what they view as massive human rights violations.

CBS News

California Gov. Newsom defers clemency decision as incoming LA County district attorney reviews Menendez brothers case

California Gov. Gavin Newsom will defer his decision on the Menendez brothers’ clemency petition to allow for incoming Los Angeles County District Attorney Nathan Hochman to review the case, his office announced Monday.

“The Governor respects the role of the District Attorney in ensuring justice is served and recognizes that voters have entrusted District Attorney-elect Hochman to carry out this responsibility,” Newsom’s office said in a statement. “The Governor will defer to the DA-elect’s review and analysis of the Menendez case prior to making any clemency decisions.”

Lyle and Erik Menendez have spent roughly 35 years in state prison after they were convicted in their parents’ 1989 murder. Outgoing District Attorney George Gascón sent letters in support of the brothers’ clemency to Newsom after a Netflix show and documentary revived interest in the brothers’ case.

“I strongly support clemency for Erik and Lyle Menendez, who are currently serving sentences of life without possibility of parole. They have respectively served 34 years and have continued their educations and worked to create new programs to support the rehabilitation of fellow inmates,” Gascón said in a statement before losing his re-election bid.

In an interview, Hochman said if the case is not resolved by a Nov. 25 habeas petition hearing — when a judge will hear a motion requesting to vacate the first-degree murder convictions — he will review the case to determine whether or not to recommend resentencing.

Hochman, who will be sworn in on Dec. 2, indicated that he would petition the court for additional time to review the cast ahead of the resentencing hearing scheduled for Dec. 11.

“I wouldn’t engage in delay for delay’s sake because this case is too important to the Menendez brothers,” Hochman said in an interview earlier in November. “It’s too important to the victims’ family members. It’s too important to the public to delay more than necessary to do the review that people should expect from a district attorney.”

Such an analysis of the case would involve reviewing thousands of pages of prison files and transcripts of the months-long trials as well as speaking with law enforcement, prosecutors, defense counsel and victims’ family members, he added.

“Whatever position I ultimately end up taking, people should expect that I spent a long time thinking about it, analyzing the evidence,” Hochman said. “But my 34 years of criminal justice experience — involving hundreds of cases as a prosecutor and a defense attorney — allow me to work quickly and expeditiously in conducting this type of thorough review because I’ve done it in many, many cases before.”

After being arrested for their parents’ deaths in 1990, the Menendez brothers went through two trials where prosecutors argued that they murdered their parents because of greed. However, the siblings testified that they killed their parents in self-defense. The brothers told the jury about the alleged sexual abuse they said they experienced at the hands of their father during an emotional, highly publicized first trial.

Following closing arguments, the jurors spent roughly four days deliberating but failed to come to a unanimous decision. The judge declared a mistrial after the jury was unable to deliver a decision.

In the next and final trial, the presiding judge did not allow the defense to submit some evidence connected to the sexual abuse allegations. Prosecutors argued the brothers were lying about the allegations.

The second jury convicted Erik and Lyle Menendez of first-degree murder in 1995 and sentenced them to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

CBS News

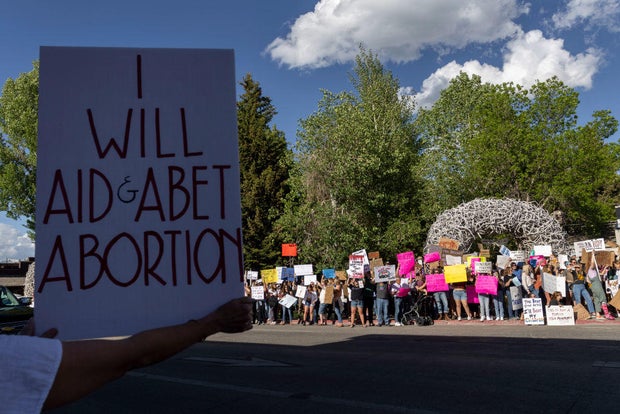

Wyoming abortion laws, including ban on pills to end pregnancy, struck down by state judge

A state judge on Monday struck down Wyoming’s overall ban on abortion and its first-in-the-nation explicit prohibition on the use of medication to end pregnancy in line with voters in yet more states voicing support for abortion rights.

Since 2022, Teton County District Judge Melissa Owens has ruled consistently three times to block the laws while they were disputed in court.

The decision marks another victory for abortion rights advocates after voters in seven states passed measures in support of access.

One Wyoming law that Owens said violated women’s rights under the state constitution bans abortion except to protect a pregnant woman’s life or in cases involving rape and incest. The other made Wyoming the only state to explicitly ban abortion pills, though other states have instituted de facto bans on the medication by broadly prohibiting abortion.

The laws were challenged by four women, including two obstetricians, and two nonprofit organizations. One of the groups, Wellspring Health Access, opened as the state’s first full-service abortion clinic in years in April 2023 following an arson attack in 2022.

“This is a wonderful day for the citizens of Wyoming — and women everywhere who should have control over their own bodies,” Wellspring Health Access President Julie Burkhart said in a statement.

NATALIE BEHRING / Getty Images

The recent elections saw voters in Missouri clear the way to undo one of the nation’s most restrictive abortion bans in a series of victories for abortion rights advocates. Florida, Nebraska and South Dakota, meanwhile, defeated similar constitutional amendments, leaving bans in place.

Abortion rights amendments also passed in Arizona, Colorado, Maryland and Montana. Nevada voters also approved an amendment in support of abortion rights, but they’ll need to pass it again it 2026 for it to take effect. Another that bans discrimination on the basis of “pregnancy outcomes” prevailed in New York.

The abortion landscape underwent a seismic shift in 2022 when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, a ruling that ended a nationwide right to abortion and cleared the way for bans to take effect in most Republican-controlled states.

Currently, 13 states are enforcing bans on abortion at all stages of pregnancy, with limited exceptions, and four have bans that kick in at or about six weeks into pregnancy — often before women realize they’re pregnant.

Nearly every ban has been challenged with a lawsuit. Courts have blocked enforcement of some restrictions, including bans throughout pregnancy in Utah and Wyoming. Judges struck down bans in Georgia and North Dakota in September 2024. Georgia’s Supreme Court ruled the next month that the ban there can be enforced while it considers the case.

In the Wyoming case, the women and nonprofits who challenged the laws argued that the bans stood to harm their health, well-being and livelihoods, claims disputed by attorneys for the state. They also argued the bans violated a 2012 state constitutional amendment saying competent Wyoming residents have a right to make their own health care decisions.

As she had done with previous rulings, Owens found merit in both arguments. The abortion bans “will undermine the integrity of the medical profession by hamstringing the ability of physicians to provide evidence-based medicine to their patients,” Owens ruled.

The abortion laws impede the fundamental right of women to make health care decisions for an entire class of people — those who are pregnant — in violation of the constitutional amendment, Owens ruled.

Wyoming voters approved the amendment amid fears of government overreach following approval of the federal Affordable Care Act and its initial requirements for people to have health insurance.

Attorneys for the state argued that health care, under the amendment, didn’t include abortion. Republican Gov. Mark Gordon, whose administration has defended the laws passed in 2022 and 2023, did not immediately return an email message Monday seeking comment.

Both sides wanted Owens to rule on the lawsuit challenging the abortion bans rather than allow it to go to trial in the spring. A three-day bench trial before Owens was previously set, but won’t be necessary with this ruling.

CBS News

Two women told House panel Matt Gaetz paid them “for sex” via Venmo, their attorney says

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.