CBS News

Transcript: UNICEF executive director Catherine Russell on “Face the Nation,” June 30, 2024

The following is a transcript of an interview with UNICEF executive director Catherine Russell on “Face the Nation” that aired on June 30, 2024.

MARGARET BRENNAN: We turn now to the executive director of the UN agency that helps disadvantaged children in the world’s toughest places. UNICEF’s Catherine Russell joins us from New York. Good to speak with you again. I know you’re just back from Sudan, which is the largest humanitarian crisis on the planet right now. What did you learn?

CATHERINE RUSSELL: Yeah, I learned that it is a catastrophic situation for children there and there are compounding crises. First, it’s the largest displacement crisis for children around the world. So many millions of children have moved either from their homes to neighboring countries like South Sudan, Egypt, or Chad, many millions are moved inside Sudan to other places in the city trying to- or in the country trying to find some refuge. It’s also a huge challenge in terms of malnutrition, we have 4 million children who are severely malnourished, almost more than half a million of those children are severely acutely malnourished, which means that they really are on the verge of starvation. And then shockingly, almost every child in Sudan has been out of school for the last year, which is incredibly destabilizing for them for their future and certainly for the country as well.

MARGARET BRENNAN: Yes, 17 million children who are not in school.

CATHERINE RUSSELL : Yeah, shocking.

MARGARET BRENNAN: Apart from the humanitarian concern here, I know, the US intelligence community has highlighted that Sudan could become a terrorist safe haven due to this ongoing civil war. What are the conditions like for those next generations?

CATHERINE RUSSELL: The conditions are absolutely terrible. I have to say I was at a center that UNICEF supports where we were providing all sorts of services for children education, which you know, is as as we discussed a horrific problem for them not being in school, trying to provide health care, providing psychosocial support for children who are so traumatized, it’s just almost hard to imagine. It’s also- it’s just such a desperate place in so many ways. They’re so you know, they’ve been so traumatized by so much violence, and they’ve seen things that no child should ever see. And that’s really something that long term is hard to imagine how they get over it. Having said that, we are there, we’re working hard, we are getting to these children. But this ongoing conflict makes it almost impossible to provide a decent future for these kids.

MARGARET BRENNAN: A little closer to home in Haiti, I know this past week the first UN-backed foreign law enforcement forces from eight different countries arrived. This is part of a U.S.-supported effort. How quickly do you think that will make a difference for the children there?

CATHERINE RUSSELL: Well, I will say, hopefully, it will be quick, because the children there I mean, honestly, I feel like I’m sort of a broken record when I tell you how bad it is in so many places, but Haiti is really challenging because there’s so much violence. I- I was shocked by what I saw when I was there several months ago, so many children who have seen violence directly, who have experienced violence, high, high rates of sexual violence. So it’s been incredibly important to try to stabilize that situation. I think this is the first step. It’s going to take a lot of work, I think to get it done, but at least we’ll start to see some semblance, hopefully, of some security, which will make it easier for us to operate, but also give these children some prospect for a decent future that isn’t defined by violence and hunger, which is unfortunately what we’re seeing now.

MARGARET BRENNAN: And the U.S. remains the largest donor to many of these humanitarian causes, I know. There was one rare piece of good news this past week in the Middle East. I read 21 children with cancer were permitted to be medically evacuated from Gaza. This was the first evacuation since May. Why is it so hard to get sick children out?

CATHERINE RUSSELL: I’ll say this, you know, everything in Gaza is hard. It’s just the most challenging environment for us to work in. I have to say, I think that, you know, the main- main problem is a lack of security. And that makes it difficult for the children who live there. They’ve been displaced. So many times, so many children have multiple times moved, trying to seek refuge trying to get away from the bombardments. I think it’s- it’s incredibly challenging. We know we continue to see that we’re on the verge of famine there so children- they basically- it just means they don’t really know where their next meal is coming from. They also have not been in school, right? So it’s an incredibly challenging place for children. And I think, you know, it is great to find some shred of- shred of good news. And you know, when you think about it, you forget in these humanitarian situations the humanitarian crisis is so devastating that you forget that there are routine problems that children face, right? They’re not getting their vaccines, they’re not getting treatment for things like cancer or other- other sort of routine diseases and challenges that children all over the world face. So getting some of these kids out of there has been, as you say, a bright spot, but I think overall we continue to see real challenges in our ability to operate there. We need to get that situation sorted out so that children have some prospects and I think this applies to all three of the situations you’ve talked about. Children are the future. We talk about that all the time. But what does that mean? If we don’t give them a future, if we don’t make sure that they have some- some prospect of hope, and I think it’s incumbent upon all of the adults in the world to come together and to do better by these children.

MARGARET BRENNAN: I couldn’t agree more with you on that. Director Russell, thank you very much. We’ll be right back.

CBS News

A study to devise nutritional guidance just for you

It’s been said the best meals come from the heart, not from a recipe book. But at this USDA kitchen, there’s no pinch of this, dash of that, no dollops or smidgens of anything. Here, nutritionists in white coats painstakingly measure every single ingredient, down to the tenth of a gram.

Sheryn Stover is expected to eat every crumb of her pizza; any tiny morsels she does miss go back to the kitchen, where they’re scrutinized like evidence of some dietary crime.

Stover (or participant #8180, as she’s known) is one of some 10,000 volunteers enrolled in a $170 million nutrition study run by the National Institutes of Health. “At 78, not many people get to do studies that are going to affect a great amount of people, and I thought this was a great opportunity to do that,” she said.

CBS News

It’s called the Nutrition for Precision Health Study. “When I tell people about the study, the reaction usually is, ‘Oh, that’s so cool, can I do it?'” said coordinator Holly Nicastro.

She explained just what “precise” precisely means: “Precision nutrition means tailoring nutrition or dietary guidance to the individual.”

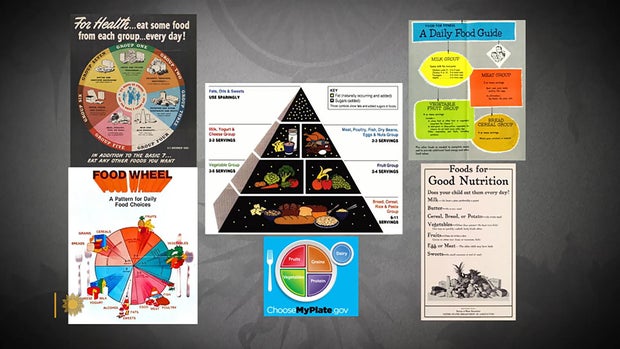

The government has long offered guidelines to help us eat better. In the 1940s we had the “Basic 7.” In the ’50s, the “Basic 4.” We’ve had the “Food Wheel,” the “Food Pyramid,” and currently, “My Plate.”

CBS News

They’re all well-intentioned, except they’re all based on averages – what works best for most people, most of the time. But according to Nicastro, there is no one best way to eat. “We know from virtually every nutrition study ever conducted, we have inner individual variability,” she said. “That means we have some people that are going to respond, and some people that aren’t. There’s no one-size-fits-all.”

The study’s participants, like Stover, are all being drawn from another NIH study program called All Of Us, a massive undertaking to create a database of at least a million people who are volunteering everything from their electronic health records to their DNA. It was from that All of Us research that Stover discovered she has the gene that makes some foods taste bitter, which could explain why she ate more of one kind of food than another.

Professor Sai Das, who oversees the study at Tufts University, says the goal of precision nutrition is to drill down even deeper into those individual differences. “We’re moving away from just saying everybody go do this, to being able to say, ‘Okay, if you have X, Y and Z characteristics, then you’re more likely to respond to a diet, and somebody else that has A, B and C characteristics will be responding to the diet differently,'” Das said.

It’s a big commitment for Stover, who is one of 150 people being paid to live at a handful of test sites around the country for six weeks – two weeks at a time. It’s so precise she can’t even go for a walk without a dietary chaperone. “Well, you could stop and buy candy … God forbid, you can’t do that!” she laughed.

While she’s here, everything from her resting metabolic rate, her body fat percentage, her bone mineral content, even the microbes in her gut (digested by a machine that essentially is a smart toilet paper reading device) are being analyzed for how hers may differ from someone else’s.

Nicastro said, “We really think that what’s going on in your poop is going to tell us a lot of information about your health and how you respond to food.”

CBS News

Stover says she doesn’t mind, except for the odd sounds the machine makes. While she is a live-in participant, thousands of others are participating from their homes, where electronic wearables track all kinds of health data, including special glasses that record everything they eat, activated when someone starts chewing. Artificial intelligence can then be used to determine not only which foods the person is eating, but how many calories are consumed.

This study is expected to be wrapped up by 2027, and because of it, we may indeed know not only to eat more fruits and vegetables, but what combination of foods is really best for us. The question that even Holly Nicastro can’t answer is, will we listen? “You can lead a horse to water; you can’t make them drink,” she said. “We can tailor the interventions all day. But one hypothesis I have is that if the guidance is tailored to the individual, it’s going to make that individual more likely to follow it, because this is for me, this was designed for me.”

For more info:

Story produced by Mark Hudspeth. Editor: Ed Givnish.

“Sunday Morning” 2024 “Food Issue” recipe index

Delicious menu suggestions from top chefs, cookbook authors, food writers, restaurateurs, and the editors of Food & Wine magazine.

CBS News

A new generation of shopping cart, with GPS and AI

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

“All hands on deck” for Idaho’s annual potato harvest

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.