CBS News

Why a hat is the mascot for the 2024 Paris Olympics

At first glance, the mascot for the 2024 Paris Olympic Games may look like a red triangle with arms, but it’s actually a Phrygian cap — a symbol of freedom in France’s history.

The mascot for both the Olympics and Paralympics was announced in 2022 with a mission of showing the world “that sport can change everything and that it deserves to have a central role in society,” according to the Olympics website.

“We wanted mascots that would embody our vision and be able to share it with the French people and the world,” 2024 Paris Games President Tony Estanguet said at the launch. “Rather than an animal, our mascots represent an ideal. The Phrygian cap is a symbol of liberty. Since it is familiar to us and appears on our stamps and the pediments of our town halls, it also represents French identity and spirit.”

The Phryges, pronounced “free-jes,” are also meant to encourage people to get active.

Where did the Phrygian cap come from?

The Phrygian cap was worn in present-day Turkey as early as 800 B.C., according to Architect of the Capitol. It was viewed as a mark of free men in classical Greece, where freed slaves wore the hat.

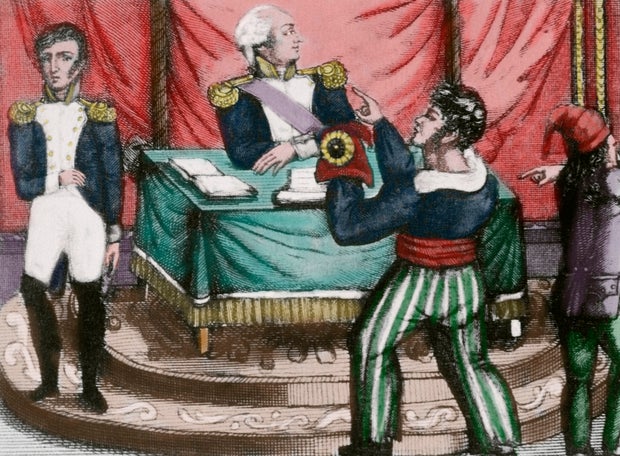

The peaked red hat has been a part of French history for centuries and was widely popularized by French revolutionaries, donned during the French Revolution of 1789. It can be seen on busts of Marianne, a woman considered “the embodiment of the French Republic,” according to Olympics organizers.

PHAS/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The caps were worn when Paris’ Notre-Dame cathedral was being built in 1163, according to the Olympics. Workers building the Eiffel Tower also wore the red hats.

Phrygian caps also made their way to the U.S., according to Architect of the Capitol, the hat appeared in images from the American Revolution. It was used in early 19th century American art and coins.

The Olympic and Paralympic Phryge

The official Olympic website describes the mascot as a thoughtful and astute strategist.

“Just like the Olympic athletes, she knows the importance of measuring all the various parameters to achieve her goals. With her sharp mind, she is modest and prefers to hide her emotions,” the website description reads. “The Olympic Phryge will lead the movement of all those who take part in sport, and believe us, she will give her all to get France moving!”

claudio_villa / Getty Images

A version of the mascot for the Paralympics has a running prosthetic.

“Her passion is to blaze a trail; some might say she is fearless, which might be true, but one thing is certain: she hates being bored and loves to try new things,” the website description reads. “No matter the sport, and regardless of whether she competes as part of a team or on her own, she is always game to play.”

What are past Olympic mascots?

The mascots chosen for the Olympic and Paralympic games each year are considered ambassadors embodying the spirit of the Olympics, according to the Olympics. They’ve been around since the 1968 Games, when the Winter Games were hosted in Grenoble, France. The first mascot was a little man, named Shuss, on skis. While the Paris mascot was chosen well in advance, Shuss was designed in a hurry — his designer had just one night to prepare a submission.

The 1972 Munich Games featured Waldi, a dachshund. Waldi was the first mascot in the history of the Olympic Summer Games.

Since then, there’s been Schneemandl the snowman, Amik the beaver, Sam the eagle, Hodori the tiger and Bing Dwen Dwen, among other characters.

“They’re tasked with giving concrete form to the Olympic spirit, spreading the values highlighted at each edition of the Games; promoting the history and culture of the host city; and giving the event a festive atmosphere,” according to the Olympics.

CBS News

New discoveries could rewrite the history of early Americans — and the 4-ton sloths they lived with

Sloths weren’t always slow-moving, furry tree-dwellers. Their prehistoric ancestors were huge – up to 4 tons – and when startled, they brandished immense claws.

For a long time, scientists believed the first humans to arrive in the Americas soon killed off these giant ground sloths through hunting, along with many other massive animals like mastodons, saber-toothed cats and dire wolves that once roamed North and South America.

But new research from several sites is starting to suggest that people came to the Americas earlier – perhaps far earlier – than once thought. These findings hint at a remarkably different life for these early Americans, one in which they may have spent millennia sharing prehistoric savannas and wetlands with enormous beasts.

“There was this idea that humans arrived and killed everything off very quickly – what’s called ‘Pleistocene overkill,'” said Daniel Odess, an archaeologist at White Sands National Park in New Mexico. But new discoveries suggest that “humans were existing alongside these animals for at least 10,000 years, without making them go extinct.”

Some of the most tantalizing clues come from an archaeological site in central Brazil, called Santa Elina, where bones of giant ground sloths show signs of being manipulated by humans. Sloths like these once lived from Alaska to Argentina, and some species had bony structures on their backs, called osteoderms – a bit like the plates of modern armadillos – that may have been used to make decorations.

Júlia d’Oliveira / AP

In a lab at the University of Sao Paulo, researcher Mírian Pacheco holds in her palm a round, penny-sized sloth fossil. She notes that its surface is surprisingly smooth, the edges appear to have been deliberately polished, and there’s a tiny hole near one edge.

“We believe it was intentionally altered and used by ancient people as jewelry or adornment,” she said. Three similar “pendant” fossils are visibly different from unworked osteoderms on a table – those are rough-surfaced and without any holes.

These artifacts from Santa Elina are roughly 27,000 years old – more than 10,000 years before scientists once thought that humans arrived in the Americas.

Originally researchers wondered if the craftsmen were working on already old fossils. But Pacheco’s research strongly suggests that ancient people were carving “fresh bones” shortly after the animals died.

Her findings, together with other recent discoveries, could help rewrite the tale of when humans first arrived in the Americas – and the effect they had on the environment they found.

“There’s still a big debate,” Pacheco said.

“Really compelling evidence”

Scientists know that the first humans emerged in Africa, then moved into Europe and Asia-Pacific, before finally making their way to the last continental frontier, the Americas. But questions remain about the final chapter of the human origins story.

Pacheco was taught in high school the theory that most archaeologists held throughout the 20th century. “What I learned in school was that Clovis was first,” she said.

Clovis is a site in New Mexico, where archaeologists in the 1920s and 1930s found distinctive projectile points and other artifacts dated to between 11,000 and 13,000 years ago.

This date happens to coincide with the end of the last Ice Age, a time when an ice-free corridor likely emerged in North America – giving rise to an idea about how early humans moved into the continent after crossing the Bering land bridge from Asia.

Mary Conlon / AP

And because the fossil record shows the widespread decline of American megafauna starting around the same time – with North America losing 70% of its large mammals, and South America losing more than 80% – many researchers surmised that humans’ arrival led to mass extinctions.

“It was a nice story for a while, when all the timing lined up,” said paleoanthropologist Briana Pobiner at the Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program. “But it doesn’t really work so well anymore.”

In the past 30 years, new research methods – including ancient DNA analysis and new laboratory techniques – coupled with the examination of additional archaeological sites and inclusion of more diverse scholars across the Americas, have upended the old narrative and raised new questions, especially about timing.

“Anything older than about 15,000 years still draws intense scrutiny,” said Richard Fariña, a paleontologist at the University of the Republic in Montevideo, Uruguay. “But really compelling evidence from more and more older sites keeps coming to light.”

In Sao Paulo and at the Federal University of Sao Carlos, Pacheco studies the chemical changes that occur when a bone becomes a fossil. This allows her team to analyze when the sloth osteoderms were likely modified.

“We found that the osteoderms were carved before the fossilization process” in “fresh bones” – meaning anywhere from a few days to a few years after the sloths died, but not thousands of years later.

Her team also tested and ruled out several natural processes, like erosion and animal gnawing. The research was published last year in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

One of her collaborators, paleontologist Thaís Pansani, recently based at the Smithsonian Institution, is analyzing whether similar-aged sloth bones found at Santa Elina were charred by human-made fires, which burn at different temperatures than natural wildfires.

Her preliminary results suggest that the fresh sloth bones were present at human campsites – whether burned deliberately in cooking, or simply nearby, isn’t clear. She is also testing and ruling out other possible causes for the black markings, such as natural chemical discoloration.

“A giant ground sloth”

The first site widely accepted as older than Clovis was in Monte Verde, Chile.

Buried beneath a peat bog, researchers discovered 14,500-year-old stone tools, pieces of preserved animal hides, and various edible and medicinal plants.

“Monte Verde was a shock. You’re here at the end of the world, with all this organic stuff preserved,” said Vanderbilt University archaeologist Tom Dillehay, a longtime researcher at Monte Verde.

Other archaeological sites suggest even earlier dates for human presence in the Americas.

Among the oldest sites is Arroyo del Vizcaíno in Uruguay, where researchers are studying apparent human-made “cut marks” on animal bones dated to around 30,000 years ago.

At New Mexico’s White Sands, researchers have uncovered human footprints dated to between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago, as well as similar-aged tracks of giant mammals. But some archaeologists say it’s hard to imagine that humans would repeatedly traverse a site and leave no stone tools.

Peter Hamlin / AP

“They’ve made a strong case, but there are still some things about that site that puzzle me,” said David Meltzer, an archaeologist at Southern Methodist University. “Why would people leave footprints over a long period of time, but never any artifacts?”

Odess at White Sands said that he expects and welcomes such challenges. “We didn’t set out to find the oldest anything – we’ve really just followed the evidence where it leads,” he said.

While the exact timing of humans’ arrival in the Americas remains contested – and may never be known – it seems clear that if the first people arrived earlier than once thought, they didn’t immediately decimate the giant beasts they encountered.

And the White Sands footprints preserve a few moments of their early interactions.

As Odess interprets them, one set of tracks shows “a giant ground sloth going along on four feet” when it encounters the footprints of a small human who’s recently dashed by. The huge animal “stops and rears up on hind legs, shuffles around, then heads off in a different direction.”

CBS News

7-year-old killed in Croatia knife attack

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

How holiday drinking could impact your health

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.