CBS News

Automation in agriculture offers solutions for farmers, but workers fear for their jobs

As a mist of rain sprinkled the fields around him in Homestead, Florida, Ford bemoaned how expensive it had been running a fossil fuel-powered irrigation system on his five-acre farm — and how bad it was for the planet.

Earlier this month, Ford installed an automated underground system that uses a solar-powered pump to periodically saturate the roots of his crops, saving “thousands of gallons of water.” Although they may be more costly up front, he sees such climate-friendly investments as a necessary expense — and more affordable than expanding his workforce of two.

It’s “much more efficient,” said Ford. “We’ve tried to figure out ‘How do we do it?’ with the least amount of adding labor.”

A growing number of companies are bringing automation to agriculture. It could ease the sector’s deepening labor shortage, help farmers manage costs, and protect workers from extreme heat. Automation could also improve yields by bringing greater accuracy to planting, harvesting, and farm management, potentially mitigating some of the challenges of growing food in an ever-warmer world.

But many small farmers and producers across the country aren’t convinced. Barriers to adoption go beyond steep price tags to questions about whether the tools can do the jobs nearly as well as the workers they’d replace. Some of those same workers wonder what this trend might mean for them, and whether machines will lead to exploitation.

Charlie Neibergall / AP

How autonomous is farm automation? Not completely – yet

On some farms, driverless tractors churn through acres of corn, soybeans, lettuce and more. Such equipment is expensive, and requires mastering new tools, but row crops are fairly easy to automate. Harvesting small, non-uniform and easily damaged fruits like blackberries, or big citruses that take a bit of strength and dexterity to pull off a tree, would be much harder.

That doesn’t deter scientists like Xin Zhang, a biological and agricultural engineer at Mississippi State University. Working with a team at Georgia Institute of Technology, she wants to apply some of the automation techniques surgeons use, and the object recognition power of advanced cameras and computers, to create robotic berry-picking arms that can pluck the fruits without creating a sticky, purple mess.

The scientists have collaborated with farmers for field trials, but Zhang isn’t sure when the machine might be ready for consumers. Although robotic harvesting is not widespread, a smattering of products have hit the market, and can be seen working from Washington’s orchards to Florida’s produce farms.

“I feel like this is the future,” Zhang said.

But where she sees promise, others see problems.

Frank James, executive director of grassroots agriculture group Dakota Rural Action, grew up on a cattle and crop farm in northeastern South Dakota. His family once employed a handful of farmhands, but has had to cut back due, in part, to the lack of available labor. Much of the work is now done by his brother and sister-in-law, while his 80-year-old father occasionally pitches in.

They swear by tractor autosteer, an automated system that communicates with a satellite to help keep the machine on track. But it can’t identify the moisture levels in the fields which can hamstring tools or cause the tractor to get stuck, and requires human oversight to work as it should. The technology also complicates maintenance. For these reasons, he doubts automation will become the “absolute” future of farm work.

“You build a relationship with the land, with the animals, with the place that you’re producing it. And we’re moving away from that,” said James.

Charlie Neibergall / AP

Some farmers say automation answers labor woes

Tim Bucher grew up on a farm in Northern California and has worked in agriculture since he was 16. Dealing with weather issues like drought has always been a fact of life for him, but climate change has brought new challenges as temperatures regularly hit triple digits and blankets of smoke ruin entire vineyards.

The toll of climate change compounded by labor challenges inspired him to combine his farming experience with his Silicon Valley engineering and startup background to found AgTonomy in 2021. It works with equipment manufacturers like Doosan Bobcat to make automated tractors and other tools.

Since pilot programs started in 2022, Bucher says the company has been “inundated” with customers, mainly vineyard and orchard growers in California and Washington.

Those who follow the sector say farmers, often skeptical of new technology, will consider automation if it will make their business more profitable and their lives easier. Will Brigham, a dairy and maple farmer in Vermont, sees such tools as solutions to the nation’s agricultural workforce shortage.

“A lot of farmers are struggling with labor,” he said, citing the “high competition” with jobs where “you don’t have to deal with weather.

Since 2021, Brigham’s family farm has been using Farmblox, an AI-powered farm monitoring and management system that helps them get ahead of issues like leaks in tubing used in maple production. Six months ago, he joined the company as a senior sales engineer to help other farmers embrace technology like it.”

Workers worry about losing jobs, or their rights, to automation

Detasseling corn used to be a rite of passage for some young people in the Midwest. Teenagers would wade through seas of corn removing tassels – the bit that looks like a yellow feather duster at the top of each stalk – to prevent unwanted pollination.

Extreme heat, drought and intense rainfall have made this labor-intensive task even harder. And it’s now more often done by migrant farmworkers who sometimes put in 20-hour days to keep up. That’s why Jason Cope, co-founder of farm tech company PowerPollen, thinks it’s essential to mechanize arduous tasks like detasseling. His team created a tool a tractor can use to collect the pollen from male plants without having to remove the tassel. It can then be saved for future crops.

“We can account for climate change by timing pollen perfectly as it’s delivered,” he said. “And it takes a lot of that labor that’s hard to come by out of the equation.

Charlie Neibergall / AP

Workers worry about losing jobs, or their rights, to automation

Detasseling corn used to be a rite of passage for some young people in the Midwest. Teenagers would wade through seas of corn removing tassels – the bit that looks like a yellow feather duster at the top of each stalk – to prevent unwanted pollination.

Extreme heat, drought and intense rainfall have made this labor-intensive task even harder. And it’s now more often done by migrant farmworkers who sometimes put in 20-hour days to keep up. That’s why Jason Cope, co-founder of farm tech company PowerPollen, thinks it’s essential to mechanize arduous tasks like detasseling. His team created a tool a tractor can use to collect the pollen from male plants without having to remove the tassel. It can then be saved for future crops.

“We can account for climate change by timing pollen perfectly as it’s delivered,” he said. “And it takes a lot of that labor that’s hard to come by out of the equation.”

Workers worry about losing jobs, or their rights, to automation

Detasseling corn used to be a rite of passage for some young people in the Midwest. Teenagers would wade through seas of corn removing tassels – the bit that looks like a yellow feather duster at the top of each stalk – to prevent unwanted pollination.

Extreme heat, drought and intense rainfall have made this labor-intensive task even harder. And it’s now more often done by migrant farmworkers who sometimes put in 20-hour days to keep up. That’s why Jason Cope, co-founder of farm tech company PowerPollen, thinks it’s essential to mechanize arduous tasks like detasseling. His team created a tool a tractor can use to collect the pollen from male plants without having to remove the tassel. It can then be saved for future crops.

“We can account for climate change by timing pollen perfectly as it’s delivered,” he said. “And it takes a lot of that labor that’s hard to come by out of the equation.”

Erik Nicholson, who previously worked as a farm labor organizer and now runs Semillero de Ideas, a nonprofit focused on farmworkers and technology, said he has heard from farm workers concerned about losing work to automation. Some have also expressed worry about the safety of working alongside autonomous machines but are hesitant to raise issues because they fear losing their jobs. He’d like to see the companies building these machines, and the farm owners using them, put people first.

Luis Jimenez, a New York dairy worker, agrees. He described one farm using technology to monitor cows for sicknesses. Those kinds of tools can sometimes identify infections sooner than a dairy worker or veterinarian.

They also help workers know how the cows are doing, Jimenez said, speaking in Spanish. But they can reduce the number of people needed on farms and put extra pressure on the workers who remain, he said. That pressure is heightened by increasingly automated technology like video cameras used to monitor workers’ productivity.

Automation can be “a tactic, like a strategy, for bosses, so people are afraid and won’t demand their rights,” said Jimenez, who advocates for immigrant farmworkers with the grassroots organization Alianza Agrícola. Robots, after all, “are machines that don’t ask for anything,” he added. “We don’t want to be replaced by machines.”

Charlie Neibergall / AP

— This story is a collaboration between The Associated Press and Grist. Associated Press reporters Amy Taxin in Santa Ana, California, and Dorany Pineda in Los Angeles contributed. Walling reported from Chicago.

CBS News

Latest news on China’s efforts to hack Trump, Vance and Harris campaign

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

CBS News

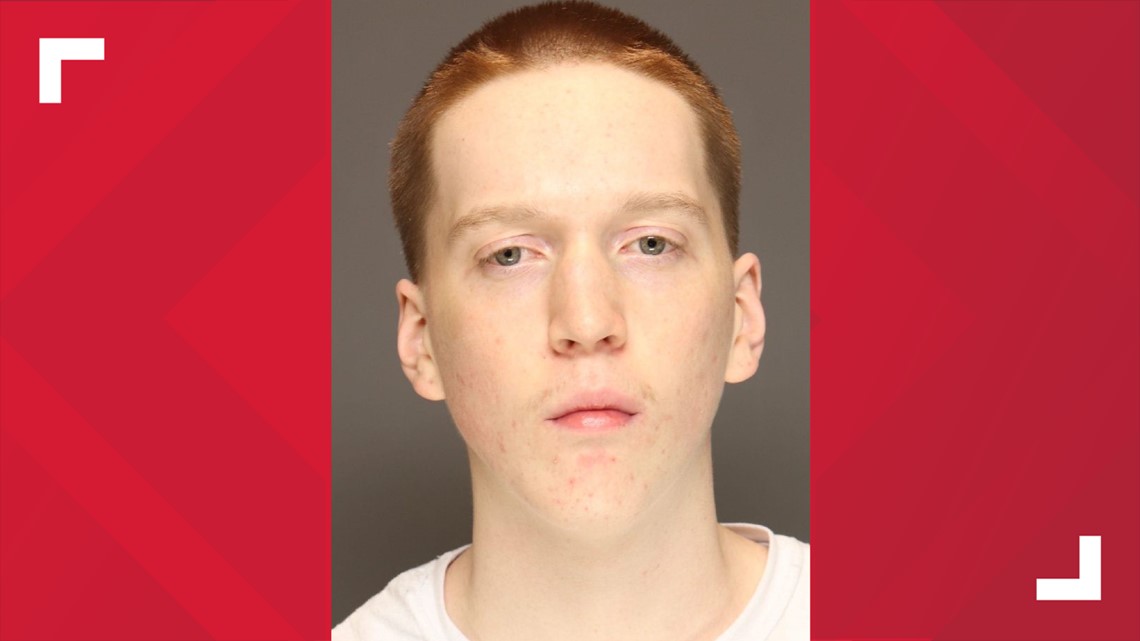

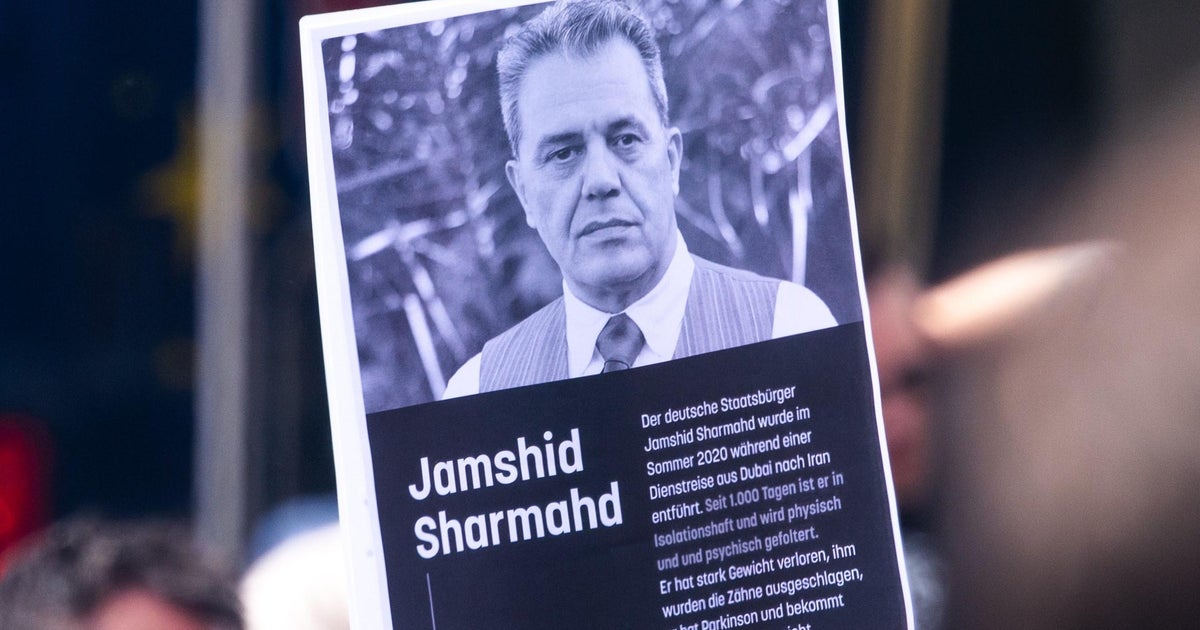

Jamshid Sharmahd, Iranian-German prisoner who lived in California, executed in Iran over disputed terror charges

Iranian-German prisoner Jamshid Sharmahd, who was kidnapped in Dubai in 2020 by Iranian security forces, has been executed in Iran after being convicted on terror charges disputed by his family, the country’s judiciary reported Monday.

Sharmahd, 69, was one of several Iranian dissidents abroad in recent years either tricked or kidnapped back to Iran as Tehran began lashing out after the collapse of its 2015 nuclear deal with world powers.

Sharmahd’s execution comes just two days after Israel launched a retaliatory strike against Iran amid the ongoing Mideast wars. While not directly linking his execution to the attack, the judiciary accused him of being “under orders from masters in Western intelligence agencies, the United States and the child-killing Zionist regime” when allegedly carrying out attacks in Iran.

The judiciary’s Mizan news agency reported his execution took place Monday morning, without offering details. Iran, one of the world’s top executioners, typically hangs condemned prisoners at sunrise.

Iran accused Sharmahd, who lived in Glendora, California, for two decades, of planning a 2008 attack on a mosque that killed 14 people and wounded over 200 others, as well as plotting other assaults through the Kingdom Assembly of Iran opposition group and its Tondar militant wing.

Photo by Ying Tang/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Iran also accused Sharmahd of “disclosing classified information” on missile sites of Iran’s paramilitary Revolutionary Guard during a television program in 2017.

“Without a doubt, the divine promise regarding the supporters of terrorism will be fulfilled, and this is a definite promise,” the judiciary said in announcing his execution.

Sharmahd’s family disputed the allegations and had worked for years to see him freed. They could not be immediately reached for comment.

Germany expelled two Iranian diplomats in 2023 over Sharmahd’s death sentence. The U.S. State Department has referred to Iran’s treatment of Sharmahd as “reprehensible” and described him facing a “sham trial.”

The German government and the U.S. State Department did not immediately respond to a request for comment Monday.

Amnesty International said the proceedings against Sharmahd had been a “grossly unfair trial” because he had been denied access to an independent lawyer and “the right to defend himself.”

“The government-appointed lawyer said that without payment of $250,000 from the family, he would not defend Jamshid Sharmahd in court and would only ‘sit there,'” Amnesty said in one report on his case.

However, Amnesty noted that Sharmahd ran a website for the Kingdom Assembly of Iran and its Tondar militant wing that included claims of “responsibility for explosions inside Iran,” though he repeatedly denied being involved in the attacks.

Sharmahd had been in Dubai in 2020 while on his way to India for a business deal involving his software company. He was hoping to get a connecting flight despite the ongoing coronavirus pandemic disrupting global travel at the time.

Sharmahd’s family received the last message from him on July 28, 2020. It’s unclear how the abduction happened. But tracking data showed Sharmahd’s mobile phone traveled south from Dubai to the city of Al Ain on July 29, crossing the border into Oman. On July 30, tracking data showed the mobile phone traveled to the Omani port city of Sohar, where the signal stopped.

Two days later, Iran announced it had captured Sharmahd in a “complex operation.” The Intelligence Ministry published a photograph of him blindfolded.

His daughter, Gazelle Sharmahd, saw her father appear on Iranian TV in a courtroom, looking petrified.

“He’s forced to confessions about crimes he did not commit,” Gazelle Sharmahd told “60 Minutes” recently. “The charge that they gave him is corruption on Earth. That’s why he got the death sentence.”

Koosha Mahshid Falahi / AP

Iran carries out the highest number of executions annually after China, according to rights groups, including Amnesty International. The number of executions in 2023 was the highest recorded since 2015 and marked a 48% increase from 2022, and a 172% increase from 2021, Amnesty said.

According to Human Rights Watch, Iran executed at least 87 people in August, including 29 in one day.

CBS News

Can Puerto Rico vote in U.S. presidential elections? What to know amid backlash from Trump rally comment

Washington — Voters in Puerto Rico who are angered by an offensive remark about the island at former President Donald Trump’s campaign rally at Madison Square Garden in New York on Sunday have little recourse because residents of the territory cannot vote in the presidential election.

But there are millions of Puerto Ricans living in one of the 50 states who are eligible to vote. According to the Pew Research Center, Puerto Ricans make up the second-largest Hispanic voting group, with nearly 6 million voters living in the mainland U.S. as of 2021. Pennsylvania in particular has a sizable Puerto Rican population whose votes could make a difference in the battleground state.

Days before Election Day, Trump’s campaign is trying to distance itself from comedian Tony Hinchcliffe who made several racist and crude insults toward minorities at the rally, including calling Puerto Rico a “floating island of garbage.”

Can Puerto Ricans vote in U.S. presidential elections?

There are 3.4 million residents living on the island of Puerto Rico, according to the 2020 Census. Those residents of Puerto Rico are not permitted to vote in presidential elections, though they’re U.S. citizens and can participate in the Republican and Democratic presidential primaries.

Puerto Ricans can vote in federal elections if they live in one of the 50 states or Washington, D.C., and are registered to vote.

What did Tony Hinchcliffe say about Puerto Rico at the Trump rally?

Racist jokes made by comedian Tony Hinchcliffe, who goes by the stage name Kill Tony, overshadowed what was supposed to be Trump’s closing message.

“I don’t know if you guys know this, but there’s literally a floating island of garbage in the middle of the ocean right now. I think it’s called Puerto Rico,” Hinchcliffe said.

Trump’s campaign said Hinchcliffe’s jokes, which also included offensive jokes about Black people and Latinos, were not pre-approved or reviewed by the campaign.

“This joke does not reflect the views of President Trump or the campaign,” senior adviser Danielle Alvarez said in a statement.

Why isn’t Puerto Rico a state?

There’s been a yearslong debate over the status of Puerto Rico, which became a U.S. territory in 1898 after Spain ceded it to the U.S. following the Spanish-American War.

Congress has been reluctant to give Puerto Rico statehood because of the potential economic costs, as well as concerns about how it would change the balance of power in Washington.

If it became a state, two senators would be added to the Senate and it would receive proportional representation in the House.

Puerto Rico has held a series of nonbonding votes on its relationship with the U.S., most recently in 2020 in which more than half of voters said the island should be granted statehood.

What other U.S. territories are excluded from presidential elections?

Like Puerto Rico, residents of these U.S. territories cannot vote in presidential elections: American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Except for residents of American Samoa, those born in the other four American territories are U.S. citizens and can vote in federal elections if they live in one of the 50 states or Washington, D.C. Residents of American Samoa, who are U.S. nationals, are not eligible to vote in federal elections even if they live in one of the states.