CBS News

Smith Island residents try to preserve Chesapeake Bay home amid climate change | 60 Minutes

Smith Island doesn’t sit in the middle of Chesapeake Bay, so much as it bobs there. Time marches on while the land recedes, turning to marsh as sea levels rise, storms come fierce, and erosion unleashes its ground game… We talk often about what climate change does to far away continents, countries and cities. But its impact in the U.S. might be felt most sharply in a small coastal community…a Maryland island struggling to survive, where crabs are plentiful, crime is non-existent, and the residents—who trace their lineage and dialect back to the 1600s—might be among this country’s first climate refugees.

Not even 100 miles from D.C. and Baltimore, Smith Island is a tapestry of marsh land, winding creeks and mud flats. Waterfowl outnumber people here. Then again, the population—having dwindled by more than half since the 1990s—hovers around 200. With no airport or bridge, everything – groceries, utility workers, doctors, even the pastor—comes by boat, 40 minutes from the mainland. Life on the island must abide by mother nature’s fickle nature…Tides. Winds. If the weather is bad, you’re stuck.

So it is that native Smith Islanders like Mary Ada Marshall persist on a combination of spine, heart and guts….

Jon Wertheim: How do you characterize this place to people who have never been here?

Mary Ada Marshall: Alright well, I’ve been here my entire life. I don’t feel isolated, but people that come here sometimes they feel like, “I can’t get off. I can’t get to my car. I can’t”– we learn we’re survivors. We learn how to adapt with the weather, it’s like a big family. But let me tell you something, if you do wrong everybody knows it too.

Here, the school bus floats. The ambulance flies…incomes are modest—this is part of the poorest county in Maryland. The citizens live by an unwritten code based on personal morality.

Jon Wertheim: I’m wondering what role faith plays on Smith Island.

Mary Ada Marshall: A big part. That– that’s the government of our island. It really is. We– we don’t really have government much. I mean, we– we don’t have any law. We don’t need it. We don’t have–

Jon Wertheim: You don’t have any crime.

Mary Ada Marshall: No crime. Speed limit’s a golf cart. I mean, how fast can you go in a golf cart? (laugh) And — here I feel so safe. I do. I– I mean, I just feel like if I need anything that I can pick up my phone. And I don’t care what anybody’s doing, they’ll come say, “What’s the matter? What do you need?” That’s golden.

60 Minutes

Mary Ada Marshall: And you gotta have a lotta faith to live out here in the middle of this bay.

The island was first chartered by Captain John Smith in 1608. Today, most residents can draw a direct line to the first Smith Islanders to brave a life here…Tyler. Evans. Marshall. The same last names adorning the weathered gravestones adorn the mailboxes now. Among those born and raised here: Eddie Somers and Mark Kitching.

Jon Wertheim: How far do your families go back?

Mark Kitching: So my– my grandmother, the– grandmother Kitching was originally an–an Evans. And she goes back to the Tyler and Evanses, you know, way back.

Eddie Somers: 1785 on the Tyler and Evans part of me, and Somerses just came in 1870. Around 1870.

Here, the past courses through the blood; and also the brogue. Linguists come to study the singular accent—part Elizabethan English; part Southern…

Jon Wertheim: Can we talk about the accent? (laugh)

Eddie Somers: You know what I tell people about our accent? I’ll say we were here first. You all screwed (laugh) it up.

The accent is original and so is the signature Smith Island backwards talk – saying the opposite of what you mean. It’s about timing, tone and…it’s best left to the locals.

Jon Wertheim: I walk off the boat, and I say, “Smith Island isn’t anything special,” how– how’s that– how’s that get received.

Eddie Somers: We’ll tell you to get back on the boat. (laugh)

Also learning the lingo – Shanon Abbott – a newcomer from New Jersey.

Shanon Abbott: I made our– our neighbors– a casserole, I don’t know, few weeks ago. And they said, “That– that ain’t fair,” and I’m, like, okay. That means it’s good.

Jon Wertheim: How do you explain this place to people from South Jersey?

60 Minutes

Shanon Abbott: It’s like that feeling when you were a kid, like, that first day of summer vacation. And you’re, like, “Hmmm, what am I gonna do today? I’m gonna go find bugs, make mud pies, whatever it is, stay out ’til, you know, the fireflies are out at night.” That’s what this place is, to me.

Jon Wertheim: –transports you back to bein’ a girl.

Shanon Abbott: Exactly.

Time has largely been frozen here for centuries…the economy—and everything else on Smith Island—was (and is) based in, on, and around the water.

Cronkite clip: (The Sailing Oystermen) “The skipjack sailors of Chesapeake Bay who, propelled only by sail, hunt the oyster.”

Walter Cronkite saw romance in Smith Island and its watermen. That was 1965. Not much about this culture has changed since. Same methods. Same rhythms. Crabs in the summer. Oysters in the winter. Modern-day watermen like Mark Kitching see the job, yes, as a means of income, but also as an inheritance.

Jon Wertheim: What do watermen mean to this community?

Mark Kitching: Well– you know, going back– you know, you go back 75 years ago, that’s all it was. There was no– no– no– you know, no other thing but watermen.

Jon Wertheim: How many watermen now?

Mark Kitching: We’re down to about 20.

60 Minutes

By the turn of this century, fears surfaced that Smith island might not last another century. Better job opportunities on the mainland caused an exodus. There are now so few children, the island’s only school recently closed. According to the Army Corps of Engineers, erosion eats away up to 12 feet of shoreline a year and the bay is trespassing on homes. Rising tides…that don’t lift boats…In 2013, concerned about the island’s bleak and vulnerable future, the state of Maryland earmarked $1 million, encouraging residents to relocate to the mainland. the deal: we’ll buy your property…and tear down the buildings.

Eddie Somers: The homes on ’em had to be demolished and nothing could ever be built on ’em. And I said, “That’s the death of Smith Island.”

Surprisingly—or maybe not; community has always outweighed money here—not one resident took the easy payout…and the state abandoned the plan.

Jon Wertheim: What was your reaction the first time you heard about the buyout offers that were coming from the government?

Mary Ada Marshall: You really wanna know? I said, “I ain’t going nowhere. Just like everybody else.”

Still, the moment was the equivalent of a foghorn blowing…a warning. Smith Island needed saving. Suddenly watermen and retirees were learning how to apply for grants and lobby state legislators….and they’ve been strikingly successful, receiving more than $43 million for elevating roads, building jetties, restoring buildings and drawing in tourists….But the environmentalists and climate scientists we consulted worry that even Smith Island grit is no match for a rapidly changing environment.

Hilary Harp Falk is the CEO of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. She lives in Annapolis and travels all around the mid-Atlantic, fighting to preserve the bay. But her work around Smith Island is personal. This is where she spent her childhood summers.

Jon Wertheim: These pelicans we see, you– you’re saying these weren’t here when you were a girl?

Hilary Harp Falk: No. So these nesting pelicans have been moving north. They’re summering now– in– in more northern places.

Jon Wertheim: As a result of a changing climate?

Hilary Harp Falk: Correct.

Jon Wertheim: How does the rising sea level here at Chesapeake Bay compare to other bodies of water?

Hilary Harp Falk: Right now we’re expecting in Maryland to see– an increase in sea level rise by one to two feet by 2050 and more than four feet by 2100.

60 Minutes

For the record, that means the bay has the highest rate of sea level rise on the East Coast…the water that has sustained places like Smith Island has now become a threat.

Jon Wertheim: Explain why we have this high rate of sea level here.

Hilary Harp Falk: Mostly ’cause it’s really low lying. I mean, we have– we have that. We also are seeing issues of erosion as well as issues of subsidence. So we’re actually– some of the land is actually sinking.

Jon Wertheim: Some environmental scientists will say that Smith Island, these could be some of the first climate refugees in the country.

Hilary Harp Falk: And I think we’re seeing with the projections they could be right.

Jon Wertheim: 10:18:09;24 What does that tell you about the people who did stay?

Hilary Harp Falk: If you ask them, it would be because this is home. And it would be asking someone to leave their home or their hometown– to leave whole histories. And I think when you spend time here, there’s a saying that you get mud between your toes. And–

Jon Wertheim: What does that mean?

Hilary Harp Falk: It means that Smith Island never leaves you, that you will always be connected to this place. And– for those of us that have mud between our toes, I think we can understand what it means to– to not have Smith Island– anymore.

And it’s not just an abstract concern. Holland Island, just 10 miles north, was once bustling. But erosion came, people left and now, names on gravestones are the only indication of what once was. Nevertheless…the Smith Island locals say grim projections have always been part of life here.

Mary Ada Marshall: When I was a little girl they used to say, “The island’s sinking.” Now, this weren’t yesterday. This has been a long time ago. Well, fast forward 60-70 years, we’re still here, you know?

60 Minutes

Besides, they pride themselves on adapting to meet challenges. Mark Kitching isn’t driving an Uber to supplement his income; he’s using his boat to host eco tours around the pelican rookery… Mary Ada Marshall runs her business out of her kitchen making Smith Island cakes. Once baked by the island’s women to sustain their husbands during the oyster harvest, these 8-layer confections are now celebrated as the Maryland state dessert. Mary Ada takes orders by phone and then ships her creations off-island to…just about anywhere.

Mary Ada Marshall: Well I did one for Okinawa, and one for Iran and they got there. And I don’t take a cent ’til they get their cake then they mail me a check.

Jon Wertheim: They don’t pay– you don’t– they don’t pay in advance.

Mary Ada Marshall: I don’t have no credit card machine or nothing. No.

And it’s not just that the natives won’t give up. Despite the specter of sea level rise, there’s been a real estate boom here. Twenty percent of the homes on the island have changed hands in the past three years. A chance at affordable island life and optimism about the government’s infrastructure investment have led folks like Shanon Abbott to defy the warnings for a slice of Smith Island charm.

Jon Wertheim: Does the isolation worry you at all?

Shanon Abbott: No, it doesn’t. Because back home, I’m just the street address. Here, I’m Shanon. Moving here, I made a difference right away, just by moving here. Because– when were having dinner with our neighbors she said, “It’s so great just seeing the lights on.” You know, because for years, it would just– you know, they would see people move away, and the house go dark.

She and her husband paid $80,000 for this waterfront home they are now rebuilding. Not just as a place to live out their days but as a legacy.

Jon Wertheim: Did you elevate this?

Shanon Abbott: We did.

Jon Wertheim: Let’s be clear, this is no weekend house.

Shanon Abbott: This is no weekend house. This is it. We have four kids– a grandson, and we’re hoping that they will be able to bring their grandchildren and their grandchildren here.

Jon Wertheim: How do you reconcile hearing these pretty grim reports with your desire to make this this generational house?

Shanon Abbott: Five years ago, we never thought we would have a pandemic, and live through COVID. I mean, things can change tomorrow. So why worry about it? We can live in New Jersey where it’s safe. Or we can say, “Forget it, let’s– let’s really live.” Let’s be passionate about what time we have left, and who cares if we only have a hundred years left, or 75 years left, it doesn’t matter. Because something could come tomorrow, and it’d all be gone anyway.

Produced by Michelle St. John. Associate producer, Matthew Riley. Broadcast associate, Elizabeth Germino. Edited by Matt Richman.

CBS News

Syria’s civil war reignites in dramatic fashion as Russia joins airstrikes on rebels who seized Aleppo

The Syrian military and its ally Russia conducted deadly joint air raids Monday on areas that Islamist-led rebels seized control of over the weekend. The strikes were a response to a lightning offensive by the rebels that saw them wrest control of swathes of northwest Syria from government forces.

The conflict that started more than a decade ago took a significant turn several days ago, catching many — including, it seems, Syrian dictator Bashar Assad and his Russian backers — by surprise. On Saturday, rebels, including many with the U.S.-designated Islamic terrorist group Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS), took control of the major city of Aleppo in northern Syria.

The rebels seized Aleppo’s airport and started pushing into towns and villages in the countryside around the city on Sunday after leaving piles of dead government soldiers in the streets. Observers said the rebel forces were often met with little to no resistance by regime forces, but by Monday the pace of the surprise offensive appeared to have slowed, with Assad and his Russian backers ramping-up their response.

Syrian rebels’ surprise offensive

Syria’s civil war began in 2011 after civilians led pro-democracy protests against Assad, and his government responded by opening fire on its own people. The ensuing war is thought to have killed around 500,000 people but, for the last several years, it had simmered as a stalemate. Government forces have controlled the west and south of the country, American-backed rebels have dominated the northeast, and Islamist rebel factions — including the ones now in control of Aleppo — have held most of the northwest.

“We are coming Damascus,” the rebels chanted Sunday, threatening to push on next toward Syria’s national capital and the Assad government’s stronghold.

Ghaith Alsayed/AP

The balance in the stalemate started changing last week, when the Islamist-led rebel alliance in the northwest launched its offensive. Over the weekend, HTS and allied factions took control of Aleppo city for the first time since the civil war started more than a decade ago, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights war monitoring group’s director Rami Abdel Rahman.

Aleppo, an ancient city dominated by its landmark citadel, is home to two million people. It was the scene of fierce battles earlier in the conflict but, until Sunday, the rebels had never managed to totally seize it. Video showed rebels in military fatigues patrolling the streets of Aleppo, with some setting fire to a Syrian flag and others holding up the green, red, black and white flag of the revolution.

While the streets appeared mostly empty, some residents came out to cheer the advancing rebel fighters. HTS is an alliance led by al Qaeda’s former Syria branch. It’s fighting alongside allied factions, with units taking orders from a joint command.

Aron Lund of the Century International think tank said: “Aleppo seems to be lost for the regime.”

He added: “And a government without Aleppo is not really a functional government of Syria.”

The United States and its allies France, Germany and Britain called Sunday for “de-escalation” in Syria, and for the protection of civilians and infrastructure. The U.S. maintains hundreds of troops in northeast Syria as part of an anti-jihadist coalition, and it has also continued carrying out strikes against Islamist groups in the country.

Russia and Iran vow to help Syria’s Assad

Assad’s reaction to the surprise offensive was still building on Monday with the joint airstrikes carried out by his air force and his Russian allies, and expanded ground operations aimed at retaking towns and villages north of Aleppo said to be underway.

ABDULAZIZ KETAZ/AFP/Getty

Syrian-Russian air raids hammered several areas of both Aleppo and the neighboring Idlib provinces, killing at least 49 people, including 17 civilians, according to the Observatory.

“The strikes targeted… displaced families living on the edge of a displacement camp,” said Hussein Ahmed Khudur, a 45-year-old teacher who sought refuge at a camp in Idlib after fleeing fighting in Aleppo province. He said one of the five people killed in one strike was a student of his, and the other four were his four sisters.

Russia, which first intervened directly in the Syrian war in 2015, said Monday that it continued to support Assad.

MIKHAIL KLIMENTYEV/SPUTNIK/AFP/Getty

“We of course continue to support Bashar al-Assad and we continue contacts at the appropriate levels, we are analyzing the situation,” Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov told journalists.

Iran’s top diplomat Abbas Araghchi, was in Syria on Sunday to deliver a message of support, state media said.

On Monday, Iranian foreign ministry spokesman Esmail Baqaei said the Islamic republic had entered Syria at the official invitation of Assad’s government.

“Our military advisers were present in Syria, and they are still present. The presence of advisers from the Islamic Republic of Iran in Syria is not a new thing,” he said.

Same Syrian civil war, but very different times

While the fighting is rooted in a war that began more than a decade ago, much has changed since then. Millions of Syrians have become displaced, with around 5.5 million living in neighboring countries.

Most of those involved in the initial anti-Assad protests are either dead, living in exile or in jail.

Russia, meanwhile, is nearing the third year of its incredibly costly full-scale war on Ukraine, and Iran’s militant allies Hezbollah and Hamas have been massively weakened by more than a year of conflict with Israel.

On Monday, Iran’s foreign ministry said it would maintain its military support for the Syrian government.

But the role of Lebanon’s Hezbollah, which played a key role in backing the government particularly around Aleppo, remains in question particularly after it withdrew from several of its positions to focus on fighting Israel.

HTS and its allies began their offensive Wednesday, just as a ceasefire took effect in Lebanon after more than a year of war between Hezbollah and Israel.

The recent violence in Syria has killed some 244 rebels and 141 Syrian regime and allied fighters, along with at least 24 civilians, according to the Observatory, which has a network of sources inside Syria. The Observatory said rebel advances met little resistance.

Aaron Stein, president of the U.S.-based Foreign Policy Research Institute, said “Russia’s presence has thinned out considerably and quick reaction airstrikes have limited utility.”

He called the rebel advance “a reminder of how weak the [Assad] regime is.”

The airstrikes on Sunday on parts of Aleppo were the first since 2016.

and

contributed to this report.

CBS News

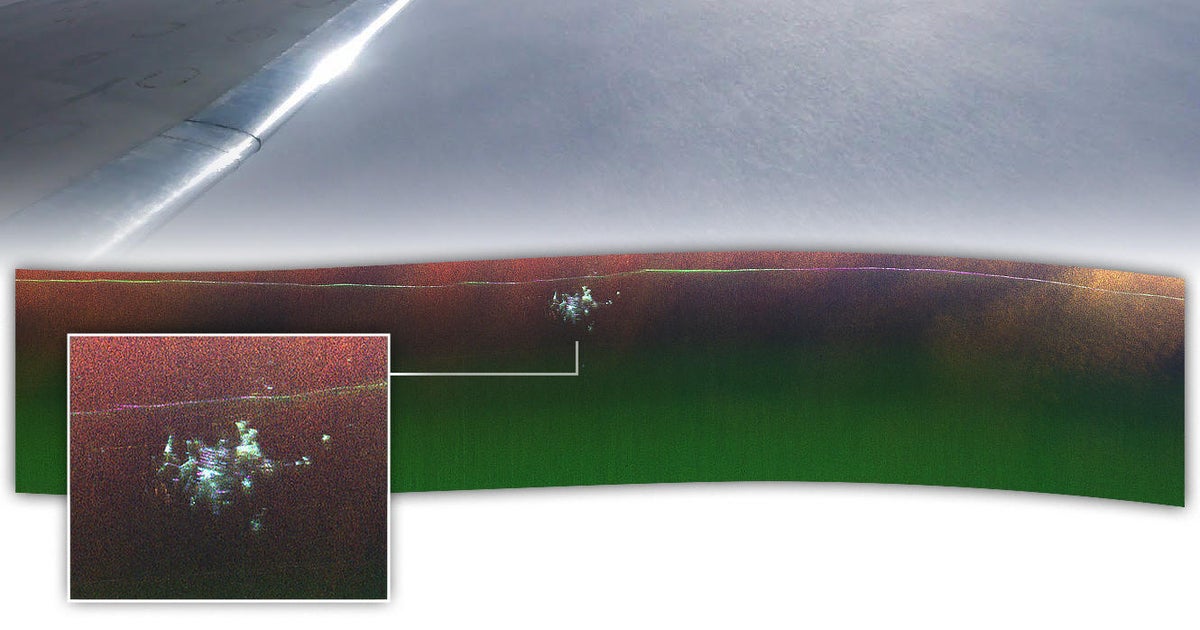

Police seize record 2.3 tons of cocaine from fishing boat that broke down off coast of Australia

Australian police seized a record 2.3 tons of cocaine and arrested 13 people in raids after the suspects’ boat broke down off the coast of Queensland, authorities said Monday.

The drugs had a sale value of 760 million Australian dollars ($494 million) and equaled as many as 11.7 million street deals if they had reached the country of 28 million people, federal police said in a statement.

Investigators told reporters in Brisbane that the drugs were transported from an unidentified South American country.

The arrests on Saturday and Sunday followed a monthlong investigation after a tipoff that the Comancheros motorcycle gang was planning a multi-ton smuggling operation, Australian Federal Police Commander Stephen Jay said. Police released photos and video of the operation, showing the cabin of the fishing boat loaded with huge packages of the alleged drugs.

Jono Searle / AP

The smugglers made two attempts to transport the drugs to Australia by sea from a mothership floating hundreds of miles offshore, Jay said. Their first boat broke down, and the second vessel foundered on Saturday, leaving the suspects stranded at sea for several hours until police raided the fishing boat and seized the drugs, he said.

The mothership was in international waters and was not apprehended, Jay said.

Authorities have seized more than one ton of cocaine before, Jay said, but the weekend’s haul was the biggest ever recorded in Australia.

Those charged are accused of conspiring to import the drug into Australia by sea and were due to appear in various courts on Monday. The maximum penalty under the charge is life in prison.

Some were arrested on the boat while others were waiting on shore to collect the cocaine, police said. Two were under age 18 and all were Australian citizens, they said.

“Australia is a very attractive market for organized criminal groups to send drugs such as cocaine,” Jay said.

The seizure marks the latest in a string of massive drug busts around the globe in recent days. On Wednesday, the Colombian navy announced that a authorities from dozens of countries seized over 225 metric tons of cocaine in a six-week mega-operation where they unearthed a new Pacific trafficking route from South America to Australia. Officials said they had also seized “increasingly sophisticated” drug-laden semisubmersibles — better known as “narco subs” — that can travel 10,000 miles without refueling.

Last week, Belgian authorities said they had seized almost five tons of cocaine stashed in shipping containers at Antwerp port, as part of a cross-border investigation into a drug-trafficking ring.

Just days before that, Spanish police said that they had seized 13 tons of cocaine — the country’s largest-ever haul of the drug — and made one arrest.

CBS News

Bob Bryar, former My Chemical Romance drummer, dead at 44

Bob Bryar, a former drummer with My Chemical Romance who played on the band’s career-defining rock opera, “The Black Parade,” has died, according to the band. He was 44.

“The band asks for your patience and understanding as they process the news of Bob’s passing,” a spokesperson for My Chemcial Romance said in a statement Sunday

The statement did not include any additional details.

Bryar replaced drummer Matt Pelissier in 2004, but in 2006 he suffered third-degree burns in an accident while on the set of a music video in 2006, the BBC reported. Bryar went on to face multiple complications from the injuries, and was hospitalized for a staph infection.

In 2010, the band posted a statement that Bryar had left, calling it a “painful decision,” the BBC reported.

Photo by Gary Miller/FilmMagic via Getty

Bryar moved on from the music business and later auctioned off a drum kit to raise money for an animal adoption center in Williamson County, Tennessee.

Next year, the band will embark on a 10-date North American stadium tour, where they will perform “The Black Parade,” released in 2006, in full.

My Chemical Romance formed in 2001 and released four studio albums across their career, first breaking through with 2004’s “Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge.” They announced their breakup in 2013; a year later, they released a greatest hits collection titled “May Death Never Stop You.” In 2019, they announced a reunion, later revealing they’d privately reunited two years earlier.

KOJI SASAHARA / AP